Evidence of depopulation and repopulation around Ground Zero. Thu 01 June 2023

Eastern England's burned and ruined towns. Source: see below

Travellers in 17th and 18th century eastern England noted the region was littered with destroyed towns, strange sand patches and destroyed monasteries.

From History of Lincolnshire - Wikipedia:

The Witham valley between Boston and Lincoln was developed with the highest concentration of Christian abbeys and monastic foundations in England. The principal foundations were Barlings Abbey, Bardney Abbey, Catley Abbey, Nocton Priory, Stainfield Abbey, Stixwould Abbey, Tupholme Abbey, Kirkstead Abbey, Kyme Abbey. There were also monastic houses at Bourne Abbey, Sempringham Abbey and many other places. But the clustering along the Witham was extraordinary. 1

Highlighting two hints in this quote:

and many other places

which means: "our list of monasteries isn't the half of it."

And the second hint:

But the clustering along the Witham was extraordinary.

Which translates as: "why were so many monasteries built here in the first place?"

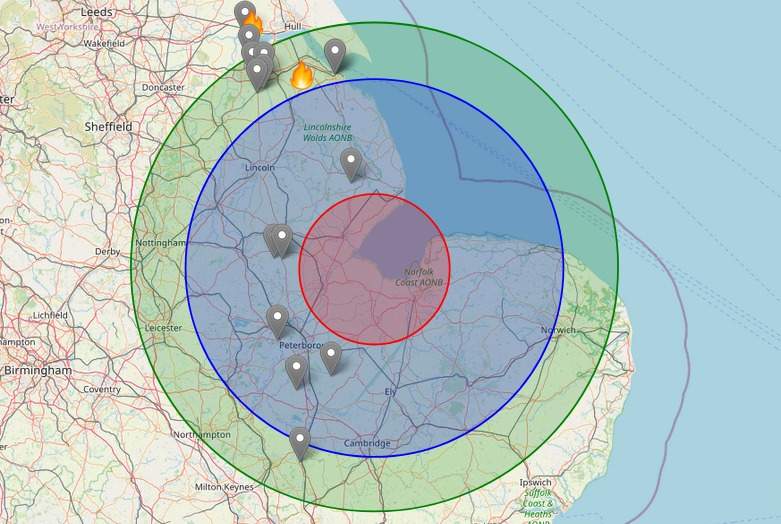

Mapping Wikipedia's list of principal monasteries (yellow markers) against the eastern England destruction zone:

Wikipedia's principal River Witham monasteries mapped against sunken church reports.

Key:

- Red marker: Documented sunken church.

- Orange marker: Legend of sunken church.

- Blue circle: Inner corridor of sunken churches.

- Green circle: Outer circle of sunken churches.

- Red circle: Change in near-surface geology shown on BGS map.

- Yellow marker: Dissolved 'monastic houses' per Wikipedia sample.

Turning to the scale of monastic destruction...

Across England and Wales, ruined monasteries tend to look like this:

Remains of Furness Abbey, Cumbria. Source

And this:

Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire, Wales. Source: Tintern Abbey

Or at worst, this:

Reading Abbey, Berkshire. Source: Reading Abbey

Overall, we see lengths of wall, a few complete doorway arches, a few complete window arches. But no roofs.

In Lincolnshire, ruined monasteries are also missing their roofs:

Remains of Kirkstead Abbey. Source: Kirkstead Abbey

And:

Remains of Barlings Abbey. Source: Barlings Abbey

And:

Remains of Tupholme Abbey. Source: Tupholme Abbey

Here are the remains of one of Lincolnshire's largest monastic houses:

Bardney Abbey, Lincolnshire. Source: Bardney Abbey

Even the humps are artificial. They were added back recently to show where the tops of columns were found.

Clearly, Lincolnshire's monastic houses aren't just lacking roofs.

These last four images weren't selected because they show particularly ruined Lincolnshire monastic houses. They were selected because they're on Wikipedia's list of 'principle' Lincolnshire monastic houses.

Crowland Abbey. View from the south east. Source

Crowland Abbey is 29km (18m) from Ground Zero:

Yellow marker: Crowland Abbey.

Given Crowland Abbey's proximity to the apparent centre of a destructive event and the state of Lincolnshire's other monastic houses, you would expect it to have been flattened.

However, let's look a little more closely at this 'ruin'. For example, the parts closest to the camera; the parts outlined in red:

Note the massive, somewhat ornate, stone pier and the high arch of single stones that springs from it.

From Crowland Abbey: History:

Much careful restoration and repair has been carried out since 1860

Twenty years into that restoration, Crowland Abbey looked like this:

Crowland Abbey 1880. View from south west. Source: Crowland Abbey

Compared to the Crowland Abbey photograph above this viewpoint is about 90 degrees to the left.

We see:

- the big, ornate south eastern pier is missing

- the high, single-stone arch that depends on that pier is also missing.

In the image above, the arch and pier should be to the right of the ruin.

In other words, the 'ancient' ruins of Crowland Abbey were faked. Crowland Abbey only looks like more complete monastic ruins because it was built in the 19th century to look like a more complete ruin.

I wrote the above before stumbling on A. S. Canham. Late in the 19th century, Canham also developed concerns about the official history of Crowland Abbey and the area around the town.

In a gently derisive account of Crowland Abbey's structural 'enigmas', A. S. Canham hinted to British Archaeological Association members why the single semi-circular arch might have been added to Crowland Abbey.

From Notes on the Archaeology of Crowland, 06-1891, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Vol 47, 1891, p292:

Lack of skilled workmen is given as a reason for a poor building, whilst it is clearly shown on the other side that long before the Conquest continental architects and masons were rearing churches in England with heavy columns and semicircular arches.

Unpacking that: the builders added the semi-circular arch to make Crowland Abbey appear really old.

Along with many other enigmas at Crowland, Canham also questioned how, beneath the town of Crowland, prehistoric man's tools were mixed with Roman cookware.

From Conflicting Theories in Fen History, A. S. Canham in Fenland notes & queries, 1889, p3:

At Crowland... several excavations were made to obtain gravel, in one of the pits chipped fiints were found almost to the bottom of the bed.

... the workshop of the semi-savage who knew nothing even of polishing his rude stone implements, but was contented to use... spear heads and arrows of the most primitive description.

stranger still, mixed indiscriminately with his urns of baked gault, were found many specimens of Roman jars and vases made on a wheel.

Crucially, Canham also pointed out that Ice Age theory couldn't explain how both the fenland's blue clay and Crowland's gravel came to lie directly above the remains of luxuriant forest interspersed with peat. The fallen forest should have rotted away before the transition to Ice Age really got underway.

Which leaves the orthodox history of Crowland standing on only one leg: Crowland's curious religious history.

In Notes on the Archaeology of Crowland, 1891, Canham went on to supply examples of Crowland's religious historians adapting logic to fit the town's 'ancient' monastic history. Many other problems with the documents created to fake Crowland's religious history have subsequently been itemised at Crowland - Kemble: The Anglo-Saxon Charters Website.

In short, Canham suspected the orthodox history of Crowland Abbey was a crock. And he suspected the orthodox history of the fens were also a crock.

From The Author of the 'Second Continuation' of the Croyland Chronicle: a fifteenth century mystery solved?, David Baldwin, East Midland Historian, Vol 4, 1994, p16:

The important chronicle which takes it [sic] name from the South Lincolnshire Abbey of Croyland is one of our best sources for the history of the fifteenth century and the War of the Roses in particular. Yet the identity of the author of the 'Second Continuation' of the Croyland Chronicle has proved to be a persistent mystery.

In other words, Croyland's fake history is the original source of part of England's fake history.

More evidence of a Fenland catastrophe

1. The green circle and eastern England's sand deserts

The green circle encompasses enigmatic 17th century cover-sands described in Desert Islands of Eastern England.

Cover-sands in the English Midlands. Map source

2. The green circle encompasses 'forgotten' lost towns:

The green circle encompasses many ruined and depopulated towns listed in Depopulated England. Eyewitness Evidence:

Vanished eastern England towns.

Key:

- Grey marker: Location of ruined or burned town.

- Fire marker: Town ruined by fire.

For more details and sources, see:

3. At the centre of the fenland blast circles is a historical mystery. It's where King John allegedly lost his 'treasure' in a flood. One version of the King John's lost treasure narrative is here; good illustrations here.

4. From within the green circle come accounts of destruction caused by fire from the sky:

Witnesses to the trail of destruction.

Key:

- Red marker: Documented sunken church.

- Orange marker: Legend of sunken church.

- Yellow marker: Dissolved 'monastic houses' per Wikipedia's excerpt above.

- Grey marker: Location of ruined or burned town.

- Black marker: Location of possible survivor report

Four locations with possible survivor reports:

Excerpted from Not the English Civil War:

1. From The Diary of Abraham de la Pryme, the Yorkshire Antiquary, Abraham de la Pryme, 1697, p154 on Grimsby's fire in the sky:

the owner built a very larg stately farm-house, like a great hall, which remained untill within the memory of man ; at which time there was plainly seen to come a great sheet of fire from out of Holderness, over the Humber, and to light upon which abbey-house, as they called it, which burnt it all down to the bare ground, with the men in it, and all the corn stacks and buildings about it. The shipmen in the road, and many more observed this sheet of fire to come thus as I have related.

Year: Within a human lifespan prior to 1697.

2. From History of the Holy Trinity Guild at Sleaford, Rev George Oliver, 1837, Chapter 2, page 92, footnote 38, on the destruction of Temple Bruer, Lincolnshire:

... horrible balls of fire breaking out near the foundations, with frequent and reiterated attacks, rendered the place, from time to time inaccessible to the scorched and blasted workmen

This, however, is now invariably affirmed and believed by all, that as they strove to force their way in by violence, the Fire which burst from the foundations of the temple, met and stopped them, and one party burned and destroyed, and another it desperately maimed

Year: Unknown. Before 1837.

3. From Invisible Helpers: Angelic Intervention in Post-Reformation England:

At Aldeburgh in Suffolk in August 1642, for instance, people were astonished by ‘an uncouth noise of war’ (beating drums, firing muskets and discharging ordnance) followed by melodious music played on various instruments and bell-ringing as if in triumph of a signal victory. Interestingly, the iconographical ‘emblem’ of the event John Vicars incorporated in his compilation of this and other ‘warning pieces’ depicted an orchestra of angels perched on a bolster of cloud: this was not a ‘representation’ of what local people had seen so much as an attempt to give visual shape to what they had heard

Year: 1642.

4. The marker for Reach, Cambridgeshire locates Christopher Marlowe's re-telling of a destructive aerial and flood event in Legends of the Fenland People. See Not the English Civil War.

Year: Unknown. Seemingly before Marlowe's death in 1593 but book includes 19th century additions.

5. Lincolnshire legends of fights in the sky may also capture aspects of these events. They are a part of wider British serpent-conflict folklore. However, Lincolnshire's legends may have been brought into the region by post-catastrophe immigrants. From County Folklore, Vol IV. Lincolnshire, Gutch and Peacock, 1908, Preface, page v:

the only striking characteristic of Lincolnshire folk-lore is its lack of originality. Nearly every superstition and custom of the county appears to be a local variant of something already familiarly known in other parts of the British islands, or beyond their limits.

Year: Unknown. Before 1908.

The arc of sunken churches coincides with a gap in Britain's folklore of serpents, dragons and witches:

A historical grey area. Source: Ice Age Sites of Britain's Serpents - Part Three

The absence of folklore in the arc may be the result of depopulation event.

Lincolnshire's high ground does have serpent conflict folklore but its characters (Bayard/Byard/Bardolph) resembles Huguenot folklore. It may have been imported when the Huegenots repopulated the Fens.

Provisional conjectures:

-

The circles mark the location of several destruction events.

-

The event involved flooding, air-burst or plasma (the 'fire' in the sky) and the movement (or creation) of very large amounts of sand.

-

Probability of survival increased with distance from the event's epicentre in the south-western Wash.

-

The event obliterated "the highest concentration of Christian abbeys and monastic foundations in England".

-

The circular green 'corridor' identifies the closest survival distance. At this distance from the Wash, enough witnesses and structures survived that we have distorted descriptions of events. Closer to the Wash, too few witnesses survived for accounts to reach us. Similarly, the surviving ruins are closer to rubble unless subsequently rebuilt.

The green circle does not identify a 'corridor' of sunken churches. Many 'sunken churches' lie under the blue circle too.

-

Assessment of survival rates:

- Red circle: very low to none.

- Blue circle: very low.

- Green circle: low.

- Outside the green circle: poor. Britain's Celtic areas may mark higher survival rates. However, evidence from Cornwall and Devon - and vitrified ruins in Scotland and northern England - suggests not. Despite being some distance from what appears to have been a destruction event, Britain's Celtic north and west offered poor survival rates.

The causative event (or sequence of events) seems to have occurred between King John's alleged calamity in 1216 and the 1642-1651 English Civil War. Floods created The Netherlands' Zuider Zee bay in 1287:

Zuider Zee around 1658. Source

Storms re-arranged England's Kent and Sussex coasts in 1287.

Does that explain the destruction around the Fens, sunken churches around the Wash and reports of fires from the sky?

Dmitry Mylnikov published evidence of a 16th-17th disaster across Eurasia and north Africa. His evidence and analysis are at:

- Другая история Земли. Часть 1а, (English: Another History of the Earth - Part One)

- Другая история Земли. Новые факты и наблюдения. Часть 1, (English: Another History of the Earth. New Facts and Observations Part One)

The images in the faster-loading Russian language versions give a sense of the evidence.

More:

- Ingulph's chronicle of the abbey of Croyland with the continuations by Peter of Blois and anonymous writers. The original fake Crowland history.

- The Mysterious Affair at Crowland Abbey, Alison Hanham. One example of the search for the author of the Croyland Chronicle.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

While the soul of a medieval Lincolnshire peasant is as important as any other, it is very difficult to explain in religious terms why the Pope invested so much in Lincolnshire's monastic houses. In theory the many large abbeys in this sparsely populated, hard to traverse county would have had no congregation. The monastic houses would have struggled to find enough workers to maintain them, let alone pray in them. Unless the 'houses' fulfilled some other purpose. ↩

More of this investigation:

On the Level About Lincolnshire,

More of this investigation:

The Reformation was a Reformatting

More by tag:

#geology