Where does the word 'pilgrim' come from? Wed 20 July 2022

Beautiful skin requires careful undressing. Source: 24 Times Claudia Schiffer Ruled the Catwalk

Undressing that preserves the value of the product:

Skin removal in a class C chap-hall. Source: Working conditions and public health risks in slaughterhouses in western Kenya

That brutal juxtaposition of photographs and captions introduces an exploration of evidence of human skin harvesting in England and Europe. Other investigations introduce evidence of former carcass processing facilities, their removal and their subsequent cover up.

If you can't cope with these two images, this analysis will likely be inappropriate for you.

In Britain, folklore of witches and serpents/dragons correlates. Where there is witch folklore, there is usually no serpent folklore; where there is serpent/dragon folklore, there is usually no witch folklore.

But both types of folklore often correlate with skinning or clothing. One of example is the narrative of the death of Yorkshire witch Mary Bateman after she was executed in 1809.

From Mary Bateman:

Strips of her skin were tanned into leather and sold as magic charms to ward off evil spirits.12 The tip of her tongue was collected by the governor of Ripon Prison. Two books from the library of Mexborough House were covered in her skin – Sir John Cheeke's Hurt of Sedition: How Grievous it is to a Common Welth (1569) and Richard Braithwaite’s Arcadian Princess (1635); the books went missing in the mid-nineteenth century.2

The Bateman account seems to be a cover-story for common practices that - apparently in the early-mid 19th century - were being stopped.

Memories of them were also being managed. That management shows up as serpent and witch folklore like the Bateman story. This series examines serpent folklore and then the witch folklore - identifying the farming practices the folklore is hiding.

Traditionally, Britain's dragon and serpent folklore has them preying for cattle and maidens near quarries. And creating 'Ice Age' hills of sand and gravel.

But look carefully and you'll see they hung with the in crowd.

The skin crowd.

From The Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday, 28 September 1782, page 2, column 3:

On Monday the 16th inst. a snake of an enormous size was destroyed at Ludham, in this county, by Jasper ANDREWS, of that place. It measured five feet eight inches long, was almost three feet in circumference, and had a very long snout; what is remarkable, there were two excrescences on the fore part of the head which very much resembled horns. This creature seldom made its appearance in the day-time, but kept concealed in subterranean retreats, several of which have been discovered in the town; one near the tanning-office, another in the premisses (sic) of the Rev. Mr JEFFREY, and another in the lands occupied by Mr William POPPLE, at the Hall. -- The skin of the above surprising reptile is now in the possession of Mr J. GARRETT, a wealthy farmer in the neighbourhood.

Just so that didn't slip by unnoticed, those Ludham tunnel locations were near the tanning office, the rectory and the Hall.

Perhaps Ludham's enormous snake provided skins to the town's 18th century elites.

The Ludham Dragon as sketched by a brave artist. Source: Hidden East Anglia

Ludham also has tales of a quarrying Devil who sounds like a little Ice Age. He digs deep pits and spills gravel as he carries the tailings away.

Britain's serpent, dragon and giant worm stories often feature earth-moving and deposits of sand and gravel near rivers. It's something many of them have in common with devils and ice ages. Perhaps folklore is hinting to us the Little Ice Age was the 'A Little More Than We're Told Age'.

Speaking of cold, there's a connection between serpents, dragons, worms and 'orms'. As in British placenames like Ormskirk in Lancashire, Ormesby in Yorkshire and South Ormsby in Lincolnshire:

A snake. Source: Black Crab

Orm. Scandinavian for 'snake'.

Revealingly, most British serpent folklore only appears when the climate starts warming up after 1700. Towards the end of the Little Ice Age:

The 17th century's forgotten freeze. Source: Little Ice Age

Variations on serpent/dragon combat folklore appear at some 100 locations across Britain. That's odd. Let's prise open the serpent's jaws and listen to what its forked tongue is really telling us.

Physical features common in serpent folklore

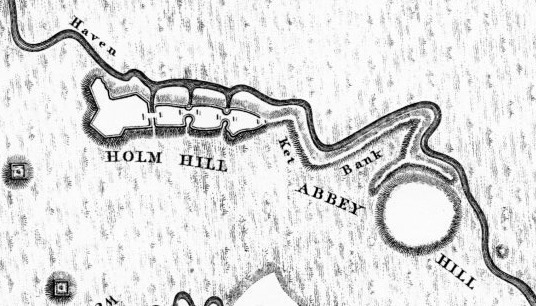

Some serpent folklore locations sound similar to mound complexes like Ohio serpent mound or Grimsby's serpent mound and (Wellow) Abbey Hilll complex, as described in 1825.

Abbey Hill and the horned - or big jawed - serpent called 'Ket Bank'. Source: The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby, Rev George Oliver, 1825

For example:

Wormy Hillock henge, in Scotland:

Wormy hillock henge was the location of a buried dragon or monster. In the legend, the dragon had been attacking villages in the neighbourhood, and the villagers eventually succeeded in killing the dragon. They then half-buried its corpse and mounded dirt over it, making a mound.

The henge is located to the south of the mound known as Wormy Hillock, on a haugh ("a piece of flat alluvial land by the side of a river")

Some folklore preserves the link between serpents and causeways.

From Blue Ben Dragon of Kilve, Somerset):

He fell from a causeway of rocks

From Knucker, Sussex:

Then bimeby, (meaning: 'blimey') he took to sitting top o' Causeway, and anybody come along there, he'd lick 'em up

From Bedd-yr-Afanc, Brynberian, Wales:

Just two rows of parallel stones survive.

Some serpent folklore records a link between serpents and earth-moving. Usually as one or more ridges on a nearby hill:

From Linton Worm, Linton, Roxburghshire and from Linton, Scottish Borders:

The writhing death throes of the Linton Worm supposedly created the curious topography of the hills of the region, an area that came to be known as "wormington". The animal retreated to its lair to die, its thrashing tail bringing down the mountain around it and burying it forever...

From Dragons & Serpents In Sussex:

A Large dragon had its den on Bignor Hill, and marks of its folds were to be seen on the hill.

Similar legends have been told of ridges around other hills, such as at Wormhill, Derbyshire.

From British Dragon Gazetteer:

A dragon once resided in the place where Stapley Farm now stands. After causing the usual havoc it was slain by an anonymous knight. The lashing of the dragons tail is said to have carved out a hollow in a field known as Wormstall.

The Laidly Worm lived in caves (ie a mine) that became a quarry:

Trough of the Laidly Worm. Source: Dragons in Folklore: Icy Sedgewick

The sunken Trough is typical of an old quarry 'dig' returning to nature.

Audrey Fletcher has done a great job showing that nearby Worm Hill was re-shaped (spoiled) by quarrying. Or is a quarry spoil heap. The creation of the Lambton Worm legend hid its early modern origins.

From The Lambton Worm, Worm Hill, Fatfield, Tyne and Wear 3 :

The worm terrorises the nearby villages, eating sheep, preventing cows from producing milk, and snatching away small children.

It is said that one can still see the marks of the worm on Worm Hill.

Lambton's Worm poses for a sketch. Source

British serpents had a taste for cattle, children and young women.

From The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh, Northumbria:

the dragon Princess Margaret is appeased by putting aside seven cows for her per day.

From Stoor Worm, Orkneys:

every Saturday the islanders provide a sacrificial offering of seven virgins, who were tied up and placed on the beach for the serpent to sweep into its mouth as it reared its head from the sea.

See also the Sockburn Worm, Sockburn, County Durham. Or scan British Dragon Gazetteer for the word 'maiden'. You'll get the picture.

And surprises wait for those who look more carefully at serpent folklore sites.

From Wormingford, Suffolk:

A band of alluvium runs beside the Stour and there are river terrace deposits south of that

The ford from which the parish takes its name (originally 'Withermund's ford') was probably that in the river Stour by the watermill, at the bottom of Church Road, where there is a sand bank in the middle of the river.

when a Bronze Age barrow nearby was destroyed in 1836 'hundreds of urns in rows' were found.

Which suggests Wormingford's serpent was highly organised and unusually dexterous. Or that Wormingford's serpent story is a cover for someone else who was highly organised and highly dexterous.

Other well-known serpent folklore includes:

- Byard's Leap - From Templars to Witch Trials

- Dragon of St Leonards Forest, Sussex

- Knucker worm, Lyminster, Sussex, who lived in a hole:

30 feet Knucker Hole, Lyminster, Sussex. Source

'Knuckers' are associated with mines and water across north west Europe. They are also known as water spirits called 'nixies', 'Nicols' and, sometimes, 'Old Nick'.

From Dragons & Serpents In Sussex:

The Dragon to be found in the Knucker Hole near Lyminster was a rampaging beast, killing livestock and humans (though some say only fair damsels), much to the annoyance of the locals. Though a water monster, it is said that the beast could fly and terrorised the countryside for miles around.

When and how was serpent combat folklore marketed?

Durham's Sockburn Worm seems to be the oldest published serpent combat story.

From Durham University's Records of Early English Drama North-East:

A book of heraldry dating from the early seventeenth century recalls the legend...

Old, yes, but not very old.

From The Monsterous Serpent of Henham, Essex:

Robert or should this be William Winstantley of Saffron Walden wrote a pamphlet titled 'The Flying Serpent or Strange News Out of Essex - A True Relation of a Monsterous Serpent seen at Henham on the Mount in Saffron Walden', published in 1699.

In the 'The Ingenious William Winstanley' by Alison Barnes, the author suggests that the dragon was a fake created by William and his uncle who built a life size working model out wood and canvas which they would have making short appearances throughout the summer of 1668, before his pamphlet was published the following January.

Alison Barnes was certainly on to something there. All credit to her.

And when we date predatory serpent, dragon and worm folklore, we find most stories start to be popularised only from the Georgian period onwards. Specifically, during the 18th century, when the Romantic movement began to write a prettier version of Britain's past.

Tales of the Sockburn Worm's neighbour - the Lambton Worm - began to circulate in 1737.

From Worm Hill:

the area found its name as far back as 1737, but it was in 1785 when its most famous association began, the legend of the Lambton Worm.

But the Lambton Worm really only coiled around audiences after 1867.

From The Curse of the Lambton Worm:

Much of the enduring fame of the Lambton Worm is owed to the song which was written for the pantomime version of ‘The Lambton Worm’ in 1867 by C.M.Leumane, and which has been adopted as a folk song. The pantomime was first performed at Tyne Theatre and Opera House

Walter Scott first publicised ballads about several more of north eastern England's most well-known serpent traditions in 1806. In a chapter of Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border - Consisting of Historical and Romantic Ballads titled "Kempion", Scott claimed the stories were old, although he admitted the Laidley Worm of Spindleston-heugh was:

Entirely composed or rewritten by Rev Mr Lamb of Norham.

Over the next 15 years Scott added more details to the Linton Dragon tale. By 1821, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Vol. III had four pages dedicated to the ballad of Linton Dragon. You might suspect Scott was rewriting the Linton Worm.

Five of the most well-known northern English serpent tales appear in writing in Rev. Thomas Parkinson's 1888 book Yorkshire Legends and Traditions - as told by her ancient chroniclers her poets and journalists.

Parkinson copied the legends from The Serpent Legends of Yorkshire - an article published in the 4 May, 1878 edition of the Victorian magazine Leisure Hour. Parkinson quotes Leisure Hour's claim that the tales were originally poems or ballads dating from the early 17th century.

Parkinson also tells the story of the Dragon of Wantley, from Wharncliffe Crags, South Yorkshire:

Source: Serpents and Dragons in British Folklore

If a single example of British serpent conflict folklore illustrates the development of Britain's serpent conflict myth, it's probably the Dragon of Wantley.

From Wikipedia:

a myth that was made into a 17th-century satirical poem and an opera by Henry Carey. The legend was mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in the opening chapter of Ivanhoe: "Here haunted of yore the fabulous Dragon of Wantley"

Great Scott! But wait, there's more.

From Serpents and Dragons in British Folklore:

A late 17thC ‘Broadside Ballad‘ from Sheffield later recorded by Francis Child (of ‘Child Ballads’ fame) in the 19thC introduces the dragon

In other words, at least two 19th century children's authors promoted the melodrama that a dragon had lived at Wantley.

The illustration is certainly more memorable than the real Dragon of Wantley's obviously quarried rock face:

The Dragon's Den at Wharncliffe Crags. Source: Wharncliffe Crags

Durham University's Records of Early English Drama North-East adds to suspicions that serpent folklore is a post-17th century melodrama created to mask these locations' real histories. From Durham University's notes on the Sockburn worm:

An extremely rare surviving account of a dragon in County Durham comes from the St. Nicholas Church in Durham city, where the parish register for 1569 records that:

A certaine Italian brought into the Cittie of Durham the 11th Day of Iune in the yeare aboue sayd A very greate, strange & monstrous serpent in length sixxteene feete, In quantitie of Dimentions greater than a great horse. Which was taken & killed by speciall pollicie in Æthiopia within the Turke’s dominions. But before it was killed, It had deuoured (as it is credibly thought) more than 1000 persons And also destroyed a whole Countrey.

We have little idea what kind of creature this ‘strange and monstrous serpent’ really was, or how serious the writer could be in thinking that it had devoured over 1,000 people, or destroyed a whole nation. Yet accounts of this Italian traveller and his curious creature feed into a folk tradition of foul serpents, worms, and dragons active in the county since before the time of the Norman Conquest.

Perhaps 'a certain Italian' really did import all 100+ serpents, dragons and worms recorded by Britain's folklore. Or perhaps 'a certain Italian' imported something else which was eventually destroyed, after which memories of it were subsequently converted into serpent, dragon and worm folklore.

Rev Parkinson probably knew that ballads and poems about serpent conflicts were being created and performed to help hide something about serpent locations. He left out part of The Serpent Legends of Yorkshire article...

The part that hinted that serpent folklore is a cover-up.

The Serpent Legends of Yorkshire carefully says:

it has been supposed, and not without reason, that our old ballad-writers and ballad-singers, or minstrels, in earlier times, under metrical legends ('ballads and poems' to you and me), also shadowed forth some powerful oppressor as a dragon or serpent, some scourge of the people, or local tyrant, whom they durst not name by his proper title; and some popular champion who vindicated the people’s rights and slew the dragon.

Serpent folklore was created to protect someone, agreed Moses Aaron Richardson. In an 1846 re-telling of the Lambton Worm story published in The Local Historian's Table Book, Richardson quotes a Mr Surtees (presumably Durham historian Robert Surtees):

perhaps no other certain deduction can be drawn from such legends, excepting that the families to which they relate are of ancient popular reputation, against whose gentle condition the memory of man runneth not to the contrary.

Richardson's italics, not mine.

For a slightly better understanding of how Britain's serpent folklore might have been designed to protect the reputation - and incomes - of certain people, we can look at Conesby Cliffe in the parish of Roxby, Lincolnshire:

Conesby Cliffe grooved rock deposit in 1894. Source: The Stone Curtain at Roxby

From The Stone Curtain at Roxby, Henry Preston, writing in Science Gossip, 1894, p193:

in the parish of Roxby-cum-Kisby, North Lincolnshire, there is a deposit of uncommon character and singular beauty.

Locally it is known as the "Sunken Church." An ancient tradition informs us that it was a church attached to one of the monasteries, and was buried by a landslip ; or, according to Abraham de la Pryme, the Yorkshire antiquary, who visited it in 1696 (Surtees Society, vol. liv.), the tradition is that the church sunk in the ground, with all the people in it, in the times of Popery.

Well, it certainly is a deposit of uncommon character, though there is another rock ridge whose enigmatic slottedness is comparable with Dragonby's:

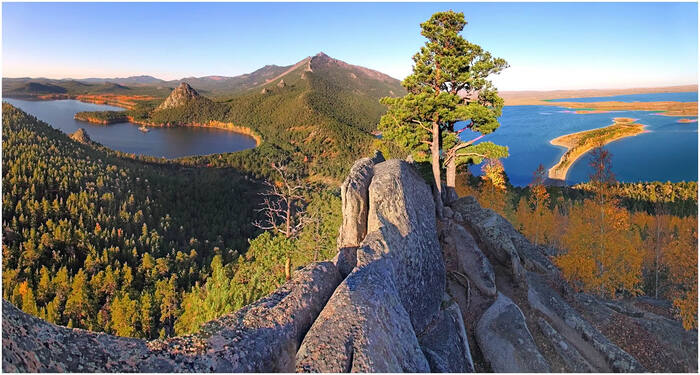

Borovoye grooved ridge, Kazakhstan. Source: Melted Megaliths and Settlements

That's the ridge that bisects the island in this centre of this photo:

Lake Borovoye, Kazakhstan. Source: Melted Megaliths and Settlements

This is the centre of Kazakhstan's Burabay National Park, whose geologicial wierdness is only hinted at on its Wikipedia page.

There are clues about the purpose of stone slots like these:

Though you're discouraged from finding them. Source: 4700 Ancient BUNKERS That Are FORBIDDEN to Open

Nor does "big rainwater gutters"'t explain the sheer scale of some of them, their construction technique, nor their global reach of their builders.

A landslip big enough to bury a north Lincolnshire church is not so inconceivable. Pryme's 17th century reports of north Lincolnshire's ruined churches and destroyed towns are at Depopulated England - Eyewitness Evidence and his reports of desert sands close to Roxby are at Desert Islands of Eastern England.

Pryme's own editor added a note saying similar sunken church stories could be found all over England and Germany. It is certainly easy to find them in eastern England:

- Santon Downham, Suffolk

- Debenham, Suffolk

- Dilham, Norfolk

- Sunken Church Field, Great Abington, Cambridgeshire

- Great Chesterford, Essex and here

- Lidgate, Suffolk

- Oby, Norfolk

More telling is how 'Conesby Cliffe' acquired its modern name: 'Dragonby'.

From Hidden Lincolnshire, Adrian Gray, p141:

its name was changed by Gervase Elwes, a successful tenor singer, to take account of the strange rock formation just to the north of the village street

Sounds like the locals already had an account for the strange rock formation, calling it "Sunken Church". But then along came Gervase Elwes - a performer of 'metrical legends' - with a replacement explanation: the dragon explanation that amuses us today.

Why create artificial serpent folklore?

-

We know some folklore was heavily rewritten in the 19th century. Gory details were removed and stories of aerial warfare were romanticised. This re-working of local memories is most detectable in the 'Celtic' edges of the British Isles. See The Celtic Gods - Comets in Irish Mythology, Mike Baillie and Patrick McCafferty. Specifically pages 14-16 and page 44 for how "strange descriptions and relationships" were turned into "simple, primitive stories". And by whom.

-

No matter where the site, serpent folklore of the British Isles tends to follow a pattern - as if they had all been created from a single folklore template. A romantic hero folklore template of the sort Thomas Carlyle would have approved.

-

Both the Irish and the British have widespread folklore of beneficial figures removing 'serpents' from their lands. St Patrick in the Celtic north and west; St Botulph, St George and various knights in the English east.

-

It's possible British serpent/dragon/worm folklore has gone through the same process as Irish folklore about aerial events. 19th century writers transformed memories of incredible physical events into incredible events performed by mythical flying entities with big appetites. Britain's serpent folklore are versions of Lugh of the Long Arm and the battles between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomorians.

-

The County of Louth, Ireland is named after Louth village, itself named after Ireland's aerial battler - Lugh of the Long Arm. The town of Louth in Lincolnshire, England, is close to the aerial battle between Hugh Bayard and a dragon (see below). Nearby is Bayons Manor - the Tealby home of the Tennyson d'Eyncourt family who apparently organised the romantisation of Ireland's and Britain's history. Between Bayons Manor, Tealby, and Louth lies one of Britain's largest 'Anglo-Saxon' cemeteries. Tealby itself is derived from Tavelesbi, Tauelesbi and Teflesbi - which means Teufels.

With this in mind we can use a new model to investigate serpent, dragon, worm events in the British Isles that fits both Maslow's Razor and the Romantic movement's re-shaping of British history:

Distribution lines and clusters visible in Britain's serpent folklore.

Key:

- Black marker: Serpent/dragon/worm battle location

- Bright yellow marker: Serpent/dragon/worm sleeping or guarding location

- Dull yellow marker: Serpent/dragon/worm landscape feature location

- Orange marker: Sunken church folklore changed to dragon folklore

Make the map full-screen and check out southern England.

Patterns in the markers:

- Many southern English serpent legend sites seem regularly spaced along routes leading to Oxford and London.

- Some sites are clustered. Examples are the Somerset Levels and West Sussex.

- England's Midlands and East Midlands have very little serpent folklore.

Why should so many British serpent folklore locations be strung along lines? The horizontal lines appear to follow pilgrim routes like the North Downs route from Kent into London. And old trackways like the Icknield Way running through the Midlands.

Why do some areas have no serpent folklore at all?

Analysis:

Britain's serpent folklore captures two classes of conflict:

- aerial conflict (knights on leaping horses, aerial fire-fights between dragons),

- sabotage (usually local peasants feeding metal-spiked food - and often themselves - to the serpent/dragon).

Map analysis of Britain's serpent folklore sites suggests the folklore captures two outcomes from physical conflict:

- Sites where memories of 'serpents' or serpent-like structures survived the conflict.

- Sites where memories remained but no trace of physical structures survived the conflict.

Interpretation:

- These are the sites of real events converted into serpent folklore after the English Civil War.

- Britain's serpent folklore was created to dilute memories of sites where humans were sorted, slaughtered and processed into food and vellum.

- The lines hint at the distribution routes through which southern England's manors, monasteries and nunneries supplied Oxford and London with humans for food, vellum and, presumably slaves and sex.

The gap over the English Midlands is very revealing. This area saw witch hunts in the middle of the 17th century. At the same time, it saw the most intense fighting in the so-called English Civil War. It also saw intense fighting in the Barons' Wars (the loss of King John's treasure) and was the preferred invasion route of the Saxons and 'The Great Heathen Army'. But no ordinary wars explain this strange gap in Britain's serpent folklore.

For an explanation, we have to look a little closer.

In the south - across Suffolk and south Cambridgeshire - the serpent folklore gap is delineated by accounts of sunken churches. In east England, there's a Lincolnshire/Norfolk gap with very little folklore... then a line of sunken church folklore... then serpent folklore to the south.

The northern edge of the serpent mythology gap is along the Yorkshire border and southern Derbyshire. There's just one account of a sunken church at Conesby Cliffe - now called Dragonby - in north Lincolnshire.

But we know there were more sunken churches in the north eastern English midlands because Depopulated England. Eyewitness Evidence includes accounts of them.

Very roughly, the River Trent marks the northern boundary of England's missing serpent folklore.

A riddle in the middle. Source: River Trent

The Trent is noted for being 'the most dynamic of all the English river systems'. It's changed its course so often it mystifies geographers. Especially glaciologist geographers.

Perhaps the fighting in this region was so intense it removed towns, changed river courses, and killed off the people who might have remembered its prior structures and their activities.

More likely, this fast and frugal rule-set outlines the actual events:

- all these wars and witch hunts are events from a single war.

- in some places Manimal Farm sites were abandoned or fought over and folk memory preserved a subsequent hunt for the site's manager. Witch hunts...

- In others Manimal Farm sites were fought over and the fight subsequently re-labelled as fight with a serpent, dragon or worm.

Why serpents?

Serpent folklore marks embarrassing locations. There is something about these locations that was attributed to 'Popery', to 'a certain Italian', and to certain families' commercial interests.

That's quite a lot of clues. Remember the references to causeways, to passages of stone? They show up in early reports of serpent mounds too:

Stress-relief for the manor's commoners. Source: AMI Tour of a Beef Packing Plant

Serpent mounds - like Grimsby's 'Ket Bank' and Loch Nell's 'Catrail' - didn't just hide what lay ahead. As with modern cattle chutes, they were also for inspection and selection.

Today we call them 'catwalks':

Same catwalk, different career path. Source: Fashion Show

Perfect skin has always been in demand.

Especially with drapers and cordwainers supplying fashionable courtiers. Note the 'court' phoneme.

But peeling skin well isn't easy.

You need an expert. A pilgrim.

Pilgrim = 'pil' as in 'peel', and 'grim' as in 'demon'.

Pilgrims were fast-working, travelling experts who specialised in peeling skins. Today they shear wool:

It's coming off like butter. A Day In The Life of a Traveling Shearer

Being upright-walkers, humans were more convenient to work on. They were shackled to open-air pillories:

Pillory from Dalarna region, Sweden. Source: Pillory

In Spanish, it's called a pilcota. Note the 'cot' sound again.

Pillories were features of Britain's squares and marketplaces:

Charing Cross pillory, London 1808. Source: Pillory

From Pillory:

Like other permanent apparatus for physical punishment, the pillory was often placed prominently and constructed more elaborately than necessary. It served as a symbol of the power of the judicial authorities, and its continual presence was seen as a deterrent, like permanent gallows for authorities endowed with high justice.

Nope.

Pillories weren't built more elaborately than necessary. Pillories were built to handle large volumes of traffic. Traffic that sometimes fought back. Using pillories to humiliate criminals was like using a four-wheel drive SUV to pick up the kids from school. The technology was designed for more challenging work.

Pilgrims travelled from markets to manor farms and monasteries - where 'ket' was processed in permanent chap-halls.

The Knights Templar were created to protect pilgrimage routes from attack.

Who was attacking the pilgrimage routes?

After Britain's monastic abbey-toir and chap-hall structures were destroyed in its 17th century 'Civil Wars', folk memories of their sites and their usage remained.

Memories that needed to be erased:

Pillory site shortly after removal. Swineshead, Lincolnshire. Source

Female ket were allowed to live longer than males. They were breeding stock. These four were lucky to be among the first generations to avoid being processed at Swineshead.

Erasing memories of 'ket' selection and slaughterhouse ket control structures is not a bad thing in itself: it's just trauma management.

It was turned into England's founding story: St George and the Dragon and a plethora of fake serpent folklore along former pilgrim routes. Serpent folklore was planted where it could compete with folk memories of each site's former use.

The brief for Britain's serpent folklore may have come from the Tennyson group centred on Cheyne Row in London. It might have looked like this:

Rewrite the 'ket' chutes as mythical serpents, dragons, worms. Leave in people's dread. Leave in the battle in the skies if you want. Create singular heroes to represent the heroes that destroyed the 'serpents'.

With this in mind, serpent folklore may still be useful. Serpent myth sites may indicate the locations of the 'ket' selection and slaughter management systems used in pre-Reformation slaughterhouses. They indicate sites that deserve special investigation.

More British serpent folklore:

-

The Atlantic Religion's collection of Serpents and Dragons in British Folklore.

-

AllAboutDragons has done a great job cataloguing and mapping many more dragon, worm and serpent legends from Britain and beyond.

-

Wyrm.org.uk has the same locations and some site photographs.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

The Yorkshire Witches: Mary Bateman, Mary Pannal and Mother Shipton, Helen Johnson, Yorkshire Post, 2018-10-31. ↩

-

The Corpse Gives Life. Executing Magic in the Modern Era: Criminal Bodies and the Gallows in Popular Medicine, Davies, Owen; Matteoni, Francesca (2017). Davies, Owen; Matteoni, Francesca (eds.). pp. 29–52 ↩↩

-

One original account of the Lambton worm is at http://www.washingtonlass.com/LambtonWormSurtees. It is also described at http://washingtonlass.com/WormHill. ↩

More of this investigation:

Ice Age Sites of Britain's Serpents,

More of this investigation:

Writing Past Wrongs

More by tag:

#enigmatic landscaping