A blast from the past may explain Ermine Street's missing section. And some of Europe's Wild Hunt folklore Fri 01 December 2023

Wild Hunt folklore hints at scorched earth warfare. Source: Netflix via Polygon

Wistman's Wood, Devon

Wistman's Wood is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) on Dartmoor, Devon:

Source: Google Maps

It's much more interesting than it looks. Much more than its SSSI status suggests.

It's associated with supernatural events. Specifically with the Wild Hunt folklore of kennels for 'wisht hounds'.

The peculiar physical characteristics of Wistman's Wood tend to be ignored behind the supernatural and the SSSI.

It lies on granite rocks just below a spring - the source of the Devonport Leat. Its boggy soil supports acid-loving plants like bilberry, lichens and moss.

Its oaks were planted in the 17th century. They are not doing well:

Source: Wistman's Wood - Wikipedia

The contorted branches of its distinctive dwarf oaks drape over boulders or trail over the boulders scattered on the site. The boulders look like a pile of old rubble.

From Wistman's Wood - Wikipedia:

A fringe of bracken surrounds much of the wood, demarcating the extent of brown earth soils.

You can see this 'zoning' of the site in the different vegetation surrounding Wistmans Wood:

Pink marks the wider area of 'brown earth'. Blue marks the patch of dwarf oaks.

Wistman's Wood is one of a cluster of Wild Hunt sites in Devon. To cut several long, strange tales short, Wisht Hounds Part 1: Wistman's Wood offers an introduction to Wild Hunt folklore. And quite a few clues about what might really be hiding inside Devon's specific folklore of wisht hounds and kennels.

Wistman's Wood, Devon.

If Wistman's Wood could be twinned with anywhere similar, it might be Vottovaara mountain in Karelia, western Russia:

"An unexplained abnormal force." Source: PreHistoric Megalithic Complex in Karelia, Russia - Vottovaara Mountain

Like Wistman's Wood, Vottovaara is scattered with precisely split rocks with unnaturally smooth surfaces, all lying around a bog.

Vottovaara Mountain anomalous zone

Key:

- Pink circle: Transitional zone in which stunting and anomalies begin

- Blue circle: Most severely twisted trees, rocks, reports of electronic equipment failures

The circles present Vottovaara's anomalous zones as perfectly regular. In reality, the mountain's contours make their boundaries somewhat more irregular.

Like Wistman's Wood, Vottovaara is host to strange tales and an array of supernatural folklore.

Noke, Oxfordshire

Noke is an Oxfordshire village by the River Ray. It too was very boggy until drained in 1824.

From Parishes: Noke - Victoria County History:

In the late 17th century [historian John] Plot found traces of what he took to be a Roman road running south from Noke to Drunshill, but this cannot now be located with certainty.

Noke also has Wild Hunt folklore. Specifically, folklore about Dandy Dogs.

Noke, Oxfordshire

Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt

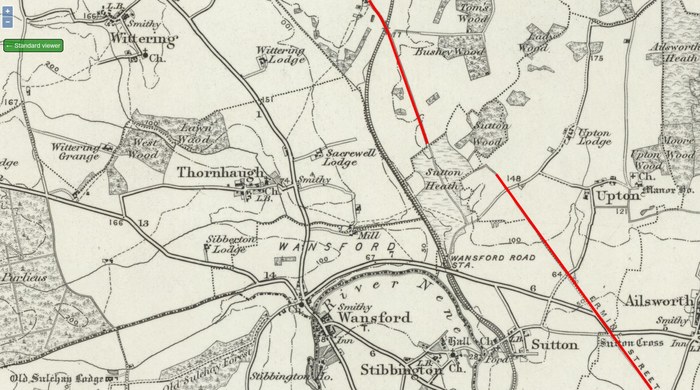

Sutton Heath is a boggy Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) on a hillside a few miles north west of Peterborough, Cambridgeshire. Sutton Heath's relatively acid soil supports rare plants in an otherwise alkaline limestone area - hence its interest to scientists:

But not to historians. Source: Sutton Heath and Bog - Wikipedia

Sutton Heath's interest to us is that it is in the centre of England's best-recorded Wild Hunt folklore: a hunt apparently witnessed in action between Peterborough and Stamford.

From Wild Hunt - Wikipedia:

Many men both saw and heard a great number of huntsmen hunting. The huntsmen were black, huge, and hideous, and rode on black horses and on black he-goats, and their hounds were jet black, with eyes like saucers, and horrible. This was seen in the very deer park of the town of Peterborough, and in all the woods that stretch from that same town to Stamford, and in the night the monks heard them sounding and winding their horns.

Peterborough's "very deer park" is now Bretton in north-west Peterborough. Bretton marks the southern end of the Wild Hunt's ten-mile path to Stamford:

Track of Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt.

From The Wild Hunt:

The Wild Hunt is a common motif in the folklore of many European cultures.

It is mentioned most often in Germanic and Norse regions. It is a part of the folklore of Britain, France, Spain, and parts of Eastern Europe as well.

In most cases, the Wild Hunt was seen as a portent of a catastrophe. It was said to appear before plagues, wars, famines, and the deaths of those who witnessed it.

In Germany, the Wild Hunt is typically led by the god Wotan, although related female deities were sometimes identified instead.

Sometimes it is lead by ... Count Hackelberg or Count Ebernberg

Or, as they said, sometimes by related female deities.

From The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, M. D., Vol III, William Stukeley, published 1887, in a diary entry dated 1737-09-10, at Castor, Peterbororough, p56:

They have still a memorial at Castor of S. Kyniburga, whom the vulgar call Lady Ketilborough, and of her coming in a coach and six, and riding over the field along the Roman road, some few nights before Michaelmas (29th September).

The awe-inspiring arrival of Lady Ketilborough - less vulgarly called Lady Hackelberg - may have been due to an enigmatic attribute of some Wild Hunt folklore. That its riders are travelling just above ground level. High enough that folklore advises those caught in their path to lie flat. If the prone were lucky, the flying riders would pass harmlessly overhead.

That doesn't sound like good advice for an encounter with the 24 hooves and four wheels of Lady Ketilborough's coach and six:

They're hard to turn, let alone stop. Source: Postal vehicle, coach and six

One account of her arrival claims she was out collecting flowers when she caught the eye of two 'ruffians'. As they chase her, flowers spill from her basket. Their seeds grow into thick woods whose tangles slow down the ruffians.

Other accounts also capture this sense of the landscape changing with magical speed.

From: Handbook for Northamptonshire and Rutland, (2nd ed.), London, Edwards Stanford, 1901, p64:

The Ermine Street... was known as “Lady Coneyborough’s Way,” from a tradition that when St. Kyneburgha was once pursued by two ruffianly assailants, the road unrolled itself before her as she fled, and thus enabled her to escape.

Early writers also claimed Lady Coneyborough's raised causeway was once 'paved with cubical bricks or tiles' 1 laid on a mortar of sand, lime and ash. That it was an engineered road, not a miracle road 2.

What magical art could unroll a brick road at speed?

Source: Amazing Construction Technologies You Must See

Today, Saint Kyniburga is popularised not for her miraculous road-building, wood-planting or rape-evasion skills but for having promoted Christianity around the fens. And for having founded an abbey at Castor and the monastery at Crowland, whose antiquity is questioned in On The Level About Lincolnshire - Part Three.

As we shall discover, Saint Kyniburga got lost in the weeds. We need to get lost in the weeds too, just for a few paragraphs, while we examine cracks in the official history of this Wild Hunt area. You can just skip the next few paragraphs if you want - they are here purely to draw attention to specific cracks in the narrative.

A Well-Travelled Girl

The many-named St. Kyneburgha/Lady Ketilborough/Lady Conyburrow/Lady Hackelberg is associated with the coming of roads and, in some variants, the coming of fertility and Christianity. And with wild hunts.

In her Saint Kyniburga version, she presents a template - a model - of Christian behaviour allocated to AD 680.

Stukeley, on the other hand, says Saint Kyneburgha died more than '600 years agoe'.

Had Stukeley said 'more than 1,000 years agoe', he would have dated Saint Kyneburgha/Lady Ketilborough's arrival to around AD 637. By choosing the odd time-span of 600 years, Stukeley nudged his readers to think she arrived around AD 1137.

The significance is that AD 1137 correlates Kyniburga's arrival with Norman suppression of English (or Saxon or Danelaw) resistance. By implication, AD 1137 also correlates her arrival with the imposition of a Norman Christian hierarchy and the coming of cathedrals.

To put it bluntly, Stukeley is implying Saint Kyniburga represented the arrival of Norman Roman Catholic Christianity. Which would probably surprise those who believe she was a pious Saxon noblewoman.

Curiously, orthodox history also claims the years immediately before 1137 were very busy for both Castor's church and the local Wild Hunt.

From The Wild Hunt:

An English account from 1127 claimed that several reliable witnesses, including monks, witnessed the Wild Hunt riding between Peterborough and Stamford over a period of nine weeks.

By hinting that her arrival was closer to AD 1127 - AD 1137, the Rev. Stukeley helpfully smeared a little more confusion about who and when this road-creating, religion-spreading entity arrived. Not that there was a shortage of confusion.

For example:

From Cyneburh (b 3. - 680) - Genealogy:

King Alcfrith and Queen Cuneburga seem to have had at least six children: King Osric of Northumbria, St. Cuneburga of Gloucester, St. Edburga of Gloucester, St. Weeda of Gloucester, St. Eva of Gloucester and the extraordinary baby St. Rumwold.

However, from The Anglo-Saxon origins of Kinbarra:

A later abbess also became a popular saint under the name of St. Kyneburga of Gloucester. Her date is uncertain, but her chapel was in use from 1147 until the Reformation; her feast day was June 25th, and her death was celebrated on April 10th.

It's not the spelling that matters: it's the implied claim that Queen Cuneburga (AKA Saint Kyniburga) had a daughter named Cuneburga (AKA Saint Cuneburga) who 500 years later became Saint Kyniburga in Gloucestershire. The second page of The Anglo-Saxon origins of Kinbarra attempts to rationalise Kyniburga's time-hop by suggesting a lot of girls were called Kyniburga and that at least three of them became saints.

The modern writers of these accounts are not wrong; but rather than untangle the disconnects and coincidences, they ignore them or try to rationalise them away.

Unlike the Victorians, who seem to have been a bit more rational than modern humans. The Victorians also knew how to detect a fake date when they saw one. For example, at Saint Kyniburgha's Castor church.

From Handbook for Northamptonshire and Rutland . (2nd ed.), London, Edwards Stanford, 1901, p62:

The inscription runs ... Dedicatio hujus ecclesie. A.D. M.C. XXIIII., thus recording the dedication as having taken place April 17, 1124. But the last figures were carved at a much later date than the rest, and are incised instead of standing in relief; and the date thus given would not be trustworthy but for its confirmation by the ‘ Peterborough Chronicle ’ (sub ann. 1124)

So the Victorians also knew when to hint that a faked date had been officially approved.

It sounds to me as though amid the general confusion-sowing and date-smearing going on around the Kyniburga entity, someone messed up carving Roman numerals on Saint Kyneburgha church, forcing local narratives to be adjusted to fit the narrative carved on the stonework.

You can even work out when - for much modern English history is a romance written by the Romantic writers from the 19th century onward. And, as it happens, the stone-inscribed dedication above was probably moved when Saint Kyneburgh church was restored in 1851.

And for those who have forgotten the volume of stonework artificially aged in the 19th century, those Romantic ruffians also seem to have jimmied with the founding date of Saint Kyneburgha's other nearby abbey at Crowland. Evidently, their jimmying seems to begin shortly after 1851.

Although ostensibly an account of a celebrated royal visit, Stukeley's re-telling of Lady Ketilborough's arrival turns out to contain other miracles that suggest a date later than AD 680 or AD 1136:

- It seems odd that a memorial to Lady Ketilborough's arrival '600 years agoe' had not been usurped by memorials to the antics of later dignitaries.

- If she came along the original Roman Ermine Street, then what was it about her arrival that left it so worthy of memorial? Given that orthodox history says the Roman road was already there before AD 680?

- If she came along the 1,500 year old, overgrown and - by 1736 - disappearing Ermine Street, she probably didn't arrive in a conventional wheeled carriage drawn by six horses.

- And if Lady Ketilborough arrived in any known form of wheeled carriage, it's unlikely she came over a field or the narrow causeway known as Lady Connyburrow's Way.

All of this can be resolved by conceiving Saint Kyneburgha, Lady Ketilborough or Lady Hackelberg as having spread religion - no to mention roads - much, much later than Castor's dodgy stonemasonry suggests.

Kyniburga's narrative also captures the opposing motives of participants common in Wild Hunt narratives.

From The Wild Hunt:

These versions of the hunt were sometimes said to have a specific prey, usually a young woman. Sometimes this was an innocent victim, but in other cases it was a female demon.

In other accounts, the hunt did not chase prey. Instead, they fought amongst themselves and would kill any unfortunate person who happened to be nearby.

This confusing range of motives attributed to Wild Hunts suggests their folklore was promulgated by locals who were very confused, was promulgated by people who wanted to the locals to become confused. Or was promulgated by people who knew the locals were confused and wanted to keep it that way.

Which they achieved by multiplying dates and names.

From The Wild Hunt:

While early medieval accounts portrayed the Wild Hunt as demonic, later romances imagined it as a host of fairies. English leaders of the Wild Hunt included Nuada, King Arthur, Herne the Hunter, Wild Edric, and King Herla.

the Wild Hunt was even led by Sir Francis Drake.

The only factors common to all Wild Hunt folklore seem to be opposing parties deploying supernatural technologies of death and travel. Or, at least, of death and Roman roadbuilding.

In this respect, Wild Hunt narratives are not so different from English history. But as Stukeley's account of Lady Ketilborough's arrival suggests, orthodox history and Wild Hunt's narratives were created from memories of real events. They were joined at the hip. Specifically, at Lady Ketilborough's hip.

The Streetwalkers

By examining Lady Ketilborough's Castor and its Wild Hunt loving neighbours, it is possible to expose a dark English secret. That examination starts with Ermine Street and why Stukeley set off to walk part of it in May 1736.

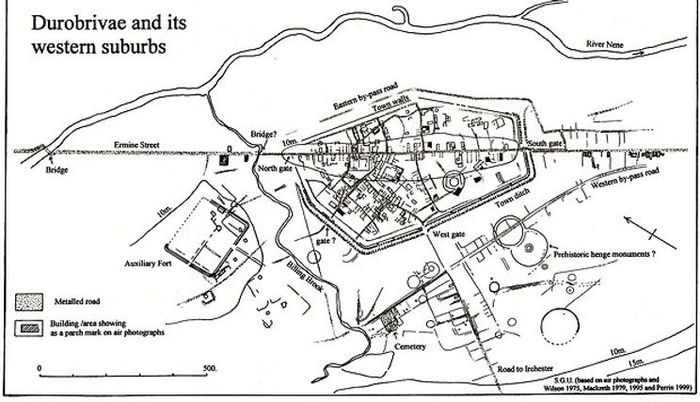

Stukeley says that he heard Castor - Roman Durobrivis - was being uncovered.

From The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, M. D., Vol III, William Stukeley, published 1887, entry dated 1736-05-21, at Castor (Durobrivis), Peterborough, p47:

They are plowing the city of Durobrivis.

It doesn't take a genius to work out that the easily accessible and well-watered River Nene meadows at Durobrivis/Castor/Water Newton should already have been well ploughed.

And well picked over.

In the 1,500 years since the Romans allegedly left, Castor's meadows had offered good grazing and Saint Kyniburgha's flower miracles, but also ready-cut stones, tiles, lead sheet and Roman nick-knacks. These they offered to anyone with a spade. Or just hands. No need for a plough, oxen or to wait until harvest. All conveniently sited by the river ready for transport and sale into Peterborough's markets just four miles downriver.

Yet, on his arrival Stukeley reported seeing Roman Castor being both dug up and pulled down:

Now they are pulling down many of the buildings, the old stately hall, selling the slate, timber, and stone.

They now dig up the stone coffins of the old lady abbesses, &c., and sell them.

They lately dug up tesselated pavements in the churchyard.

They still do dig up Romans in Castor churchyard:

Roman bodies last longer than everybody's. Source: Time Team Castor S16 Ep08

Those Roman bodies were apparently dumped on top of villa floors.

Stukeley also described 'vast foundations' and fields 'full of fragments of tiles and the like' near Cotterstock - a similar 'just-discovered in 1737' Roman site 12 miles upstream. Stukeley noted its destroyed Roman conduit had left the area boggy.

If that sounds like boggy Sutton Heath, it should. It's another site whose once well-planned, well-engineered water management system had been destroyed.

The Cotterstock site has been plowed 'time beyond memory', Stukeley speculated - while admitting that locals remembered the ruins as a large warehouse called Gildenhall Acre.

For locals, that's now probably Perio Barn. Non-locals remember similar-sounding buildings as 'The Guildhall'.

That memory of a warehouse-turned-Roman ruin is just one of many hints that Stukeley's Romans were more recent than Gladiator's Romans. And, of course, historians' Romans.

Importantly for examination of boggy Sutton Heath 12 miles to east of Cotterstock, Stukeley reminded us why some areas have lots of Roman ruins.

From The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, M. D., Vol III, William Stukeley, 1887, at Cotterstock, Northamptonshire, p51:

Between this and the water side are vast foundations, and all around the house, the like.

it was in Roman times a populous place.

That's right. Population = structures. Structures + time + <some ignored-by-convention intervention> = ruins.

32 years after Stukeley, Erming Street also baffled Charles Frederick. He was baffled by an inexplicable bend in the Roman road two miles south of Stamford.

In Some Account of the Course of the Erming-street through Northamptonshire, and of a Roman burying Place by the Side of it in the Parish of Barnack, Charles Frederick, Archaeologia Vol 1, 1770, pp 61-62:

the Erming-street enters a small paddock belonging to Thomas Noel, Esq; at Walcote, and runs just within the wall; and upon its leaving the paddock enters a large common field, where it takes a remarkable circular sweep, merely to comply with a natural ridge of the ground which runs in that form, though the ground on either side is equally dry

He probably means the orange segment on this map:

Roman Ermine Street's inexplicable curve.

Fredrick's "natural ridge of the ground which runs in that form" was ploughed out. But for 'a natural ridge of the ground', it isn't blending in very well:

The after-plough stain of an artificial ridge. Source: Google Maps

Frederick didn't comment on what Ermine Street's unnatural curve did next. How it kinked as it crossed the southern side of St Michael's priory. Better known today as Burghley House park.

But a rare, surviving account supplies some - though not all - details of what had been removed.

From Sleaford and the wapentakes of Flaxwell and Aswardhurn in the county of Lincoln, Edward Trollope, 1872, p41:

Here it is now not traceable, because its bank having been formed of gravelly materials, was carted away to make walls about Burghley House.

On both sides of Burghley, Trollope points out, the road was an embankment. He says that 'portions of its material were used for the repair of a neighbouring road' by 'overseers of St Martin's parish' who 'had in sacrilegious manner digged it up to mend their wicked ways'.

He doesn't say what was on the embankment. But we determine more details about that vanished infrastructure in Location Analysis: Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt - Part Two. We can even determine the names of the overseers themselves - in Location Analysis: Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt - Part Three.

But not the nature of their 'wicked ways'. Or how the missing infrastructure had enabled those ways.

It's to work out that very well-hidden puzzle piece that we need to look for other clues.

Here's one of them, again from Trollope, describing Ermine Street as it passes Barnack, just before Burghley House:

it may be traced in the parish of Barnack as a wide bank, thus described:

"Here it rears a high ridge, particularly in the little wood of Barnack, where it has a watch-tower upon it."

This so-called watch-tower, however, no longer exists

Yes. Watch-towers that stood by Roman roads can be somewhat embarrassing:

Neuengamme camp entrance, Bergedorf, Hamburg. Source: Concentration Camp - Frank Falla Archive

Neuengamme camp's so-called watch-tower also no longer exists.

But we see that it monitored access to and from a long, straight road. The road is built on a raised causeway with a water-filled ditch to the side. It's an assemblage familiar to any student of Roman roads. And to travellers on today's Ermine Street.

Minus the watch-towers, of course.

Barely visible in this photograph are the various ceramic insulators separating electrified fence wires from fence posts. For a better sense of how many insulators were used, see the image here. For the technically-minded, it even hints at one way of keeping them electrified.

A type of electrical insulator worth becoming familiar with - especially when exploring Roman roads - is the kind that sits inverted on a metal bracket bolted to a post:

Insulators behind inmates at Paszow labour camp, Poland. Source: Forced labour camps

In slave-owning societies, these structures are essential. Neuengamme camp and Paszow labour camp were simply modern forms of castle. With that in mind, another form is 'Besserungsanstalten' - German for a type of workhouse that offered the hope of freedom. England, however, simply called its labour camps 'workhouses'.

One can make a lot out of a missing watch-tower. But if I seem to be making something out of nothing, try back-treading along Ermine Street to the same distance 8km (5 miles) south of Castor.

To this:

The world's first prisoner-of-war camp. Source: Google Maps via Norman Cross Prison

Norman Cross was supplied by road from London and by the River Nene. It's about as far away from the River Nene at Castor as Barnack Woods. And directly linked by Ermine Street:

Norman Cross camp and Barnack Woods watch-tower

Key:

- Red markers: Norman Cross camp and Barnack Woods watch-tower

- Blue marker: Castor (Nene port)

Given it was designed to concentrate 7,000 captives - and, curiously, their apparently English children - into its central rectangular 'stockade', Norman Cross could be classed as a concentration camp.

In its time - allegedly 1797 to 1814 - it created a number of mysteries. One is why the 1,770 human remains allegedly buried in its alleged cemetery haven't been found. Another is why one inmate's adolescent son - George Borrow - claimed they were fed 'carrion'. Another is how its prisoners obtained so much bone that the artefacts they carved from it were traded across Europe and are still stored in their hundreds locally. Another is why its soup cauldron was 1.5m across and 1m deep - big enough to become a water garden feature at nearby Elton Hall. Another is why Norman Cross was called 'a depot'.

There are other Norman Cross mysteries but they don't illuminate why its cemetery is missing, where its inmates' bones went and where their skin, hair and flesh went.

If Norman Cross still seems 16 km (10 miles) too far south of the mystery of Barnack Wood's missing watch-tower, try reading Gardening: Haunts of ghostly gardeners: Who did what when?. Especially about the southern and western parts, which suggest this part of Ermine Street was once home to something about which there certainly is nothing.

The fact that Ermine Street curved to cross the southern side of Burghley Park suggests the road served a settlement near there. The curve supports local claims that Burghley Park was landscaped ('emparked') over a pre-existing settlement. As does the Burghley Park evidence analysed in The Lie of the Land.

Clues to a Vanished Town. And Palace

Like Stukeley, Charles Frederick also suspected a bigger population had once lived in this area. He suspected the amount of materials recovery going on just south of Ermine Street's inexplicable curve also pointed to a lost settlement:

it passes through the parish of Barnack in Northamptonshire, where the ground on each side of the road has been opened a large space to dig for stone; and these pits from a small Hamlet in this parish, are called Southrope [sic] pits.

In those of the west side of the road many Roman coins and antiquities have been found.

From which remains it is evident that this was a considerable burying place during the government of the Romans in this island;

evident from the vast quantity of cinders and fragments of urns found there

Helpfully, Frederick identified the northern edge of these excavations:

After passing these pits, the Erming-street enters a small paddock belonging to Thomas Noel, Esq; at Walcote

The small paddock is probably today's 'Southorpe Paddock' - just north of two more or less oblong, water-filled pits:

Southorpe pits and paddock.

Key:

- Blue marker: Southorpe pits and paddock

- Red line: Ermine Street

Frederick explained what he found odd about Southorpe's stone remains, coins and artefacts:

That it was the custom of the Romans to bury their dead without [meaning: 'outside'] their towns or cities, and most usually by the sides of their highways, is a fact known to everyone who is the least conversant in their antiquities; but the distance of this burying-place from any known Roman station, seems indeed a little extraordinary, it being at least three miles from Durobrivae [Castor]

Frederick doesn't say it but he must have thought there was an unknown Roman station nearby.

Frederick's sighting of Mr Noel's paddock offers a clue that he was hiding something or that his account has been edited.

Because if Frederick passed Noel's paddock, he must have passed the ruins of Southorpe Palace:

Site of the unmentionable: Southorpe Palace.

Key:

- Blue marker: Southorpe pits and paddock

- Black marker: Southorpe Palace site

- Red line: Ermine Street

For some reason, neither Stukeley nor Frederick mentioned Southorpe Palace, its extensive outbuildings, or its former owners. Even though, over a century later, its ruins and an alleged fishpond still appeared on maps:

The ruins are Grange Farm today. Source: National Library of Scotland

Perhaps they forgot. Perhaps their journals have been sanitised. However, there is another good reason to suspect their accounts were pruned. It's that neither Stukeley nor Frederick mentioned a very curious Ermine Street oddity just south of Southorpe palace and pits.

It's that Ermine Street comes apart as it crosses Sutton Heath:

Sutton Heath's twin Ermine Streets as mapped in 1895. Source: National Library of Scotland

Broken roads are inconvenient for road users. So roads only 'break' where it is convenient to break - in major towns. Even then, Ermine Street tended to charge straight through the middle of towns. As it had at Durobrivis a couple of miles south:

Perfect for a coach and six. Source: National Library of Scotland

Even the zigzag bridge - to the left - crossing the River Nene is a later addition.

The broken red lines on the map above show how in 1895 the northern branch of Ermine Street kinked a little to the west and ran down to what is now Sutton village. However the southern branch continues in a straight line - as if it had previously merged into Ermine Street's northern branch. This strange break suggests more than just roadway is missing from Ermine Street along its Sutton Heath stretch.

Perhaps Sutton Heath was the Roman station Frederick hinted at.

Sutton Heath's boggy land suggests Ermine Street's Roman drainage was destroyed along this stretch of road. Roman roads are characterised by attention to drainage. By their side ditches and carefully managed intersections with streams and rivers.

Absence of archaeological comment about Ermine Street's strange gap and the obvious Sutton Heath anomaly suggests they have been deliberately ignored. That suspicion is augmented by a second ignored gap. Ermine Street's missing intersection with the Fen Causeway.

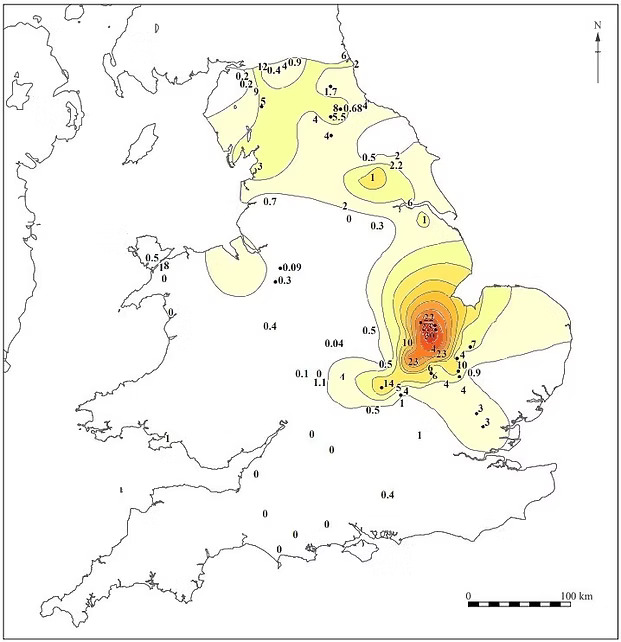

The Fen Causeway is - or was - an astonishing Roman road. Running 24 miles across the southern fens, it crossed several tidal rivers and miles of marsh on a long, large causeway. The Romans - or more likely Rome's slaves - built this engineering feat by piling gravel into an agger up to 18m (60ft) wide at its base:

Fen Causeway route. Source: Roman Britain

Key:

- Blue line: Acknowledged Fen Causeway route

- Red line: Suspected eastern Fen Causeway extension to Castle Acre, Norfolk

- Blue marker: Known Roman sites

Popular descriptions of the Fen Causeway - like Fen Causeway - Wikipedia and Fen Causeway - Roman Britain - say it connected the Roman salt works at Denver in Norfolk to the Roman port of Durobrivis (Castor/Water Newton).

That's the accepted narrative of its route.

Some investigators suspect the Fen Causeway continued east to Castle Acre ('Acre' is possibly a modern pronunciation of 'agger'). But not much is said - let alone disputed - about Fen Causeway's western end: its intersection with Ermine Street at Durobrivis/Castor/Water Newton. And it certainly should be disputed.

Fen Causeway's route was published in 1955 by Ivan D Margary who used survey data from Britain's Ordnance Survey mapping agency. This matters because Margary and Ordnance Survey mapping of Roman roads are considered to be evidence-based and authoritative.

And unlike modern narratives, Margary didn't claim Fen Causeway intersected Ermine Street at Durobrivis/Castor/Water Newton. He mapped its intersection with Ermine Street further north. To Ermine Street's strange break next to what is now Sutton Heath bog.

This map plots the details of the two roads' intersection using Margary's mapping data:

Fen Causeway intersection with Ermine Street at Sutton Heath.

Key:

- Red line: Ermine Street

- Blue line: Fen Causeway

Why would the Romans build a road most of the way to a port, then divert the road to the north and bypass the port? Roman stevedores hardly needed the extra exercise and Roman shippers didn't need the delays in loading and unloading.

Just like Stukeley, and his mention of Lady Ketilborough, this map is telling you something. Two major Roman roads joined at Sutton Heath. Then disappeared both from the ground and from the orthodox narrative. Along with Southorpe Palace and surrounding buildings. And the Ermine Street's engimatic bend.

All there is in that gap is weird Wild Hunt folklore.

Here is this enigmatic stretch of Ermine Street mapped against Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt:

A story that history won't tell.

Key:

- Red line: Ermine Street

- Blue line: Fen Causeway

- Grey line: Track of Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt

One earlier map hints when the area around Sutton Heath was sanitised:

Ermine Street crossing Sutton Heath approx 1805. Source: Archi Maps - Sutton Heath

The map shows Ermine Street still had its Sutton Heath stretch in 1805. That suggests the road disappeared in the 90 years between 1805 and the 1895 map shown above.

The earlier claim was that between those two map dates - from around 1851 onwards - this area's history was re-written.

Also suggestive on the 1805 map is the complexity of roads around Sutton Heath. The parallel stretch and road crossing to the north; the criss-cross pattern at Sutton Heath itself. They are laid out more like railway tracks in a goods yard. The changes visible in the 1895 map also suggest requirements for roads in this area were becoming more simple.

The 1805 map shows the western end of the Fen Causeway had already begun to disappear. One reason the Fen Causeway is hardly known today is its attractive gravel agger. Apparently, local farmers sold off most of its 24-mile length as building material.

Faced with missing roads and numerous roadside 'Roman quarries', conventional archaeology does admit a Romano-British settlement straddled Rome's key north-south artery at Sutton Heath. But a settlement so small most maps don't show it.

Instead archaeology prefers to draw attention to the iron and pottery finds west and south of Sutton Heath:

Nene Valley Ware find-sites. Source: Nene Valley Pottery Distribution - NVAT

We're seemingly west of Wild Hunt folklore here but that's OK because both Wild Hunt folklore and orthodox history play down the extent of physical finds and 18th century accounts of this area.

For example, from Nene Valley Roman Potteries - NVAT:

The potteries of the lower Nene Valley are concentrated on the town and suburbs of Durobrivae between Water Newton and Castor, with a further cluster close to the river near modern day Stibbington.

And here's how Stukeley described that 'cluster' in February 1736:

From The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, M. D. - Vol III, p54:

I went to Silberton, in Wansford parish... Siberton lodg (as now called) is now the only house in this once considerable town

All about here, for many acres of ground, lyes the extended carcase of a large town, houses and streets very visible.

The mass of Roman iron-working sites buried beneath woods and plantations for miles north and west of Castor tend to support Stukeley's claim. One of our challenges appreciating this is that we think Roman towns and cities were dense like ours. We don't envision them as more like vast garden surburbs connected by excellent causewayed transport networks.

The Fen Causeway being one example. Lady Coneyborough's miraculous paved way being another.

On the map below, the location of Stukeley's 'considerable town' of Silburton is suggested in yellow. Sutton Heath is shown in orange:

Ermine Street's lost suburbs in yellow and orange.

Key:

- Blue marker: Southorpe pits and paddock

- Black marker: Southorpe Palace site

- Red line: Ermine Street

- Yellow circle: Centred on Stukeley's destroyed 'considerable town'

- Orange circle: Centred on Frederick's cinder-strewn Roman remains

- Blue circle: Ruined city of Durobrivis/Castor/Water Newton

The size of the circles is my guess. Though various clues suggest even this map underplays the extent of this 'cluster' of 'Romano-British settlement'.

Curiously, in 1727, Francis Peck noted a similar pattern in the Roman settlements north of Stamford. Peck pointed out the Romans usually built settlements a day's march apart. Ten to 30 miles depending on the terrain. But despite the easy terrain, Roman towns north of Stamford - such as Great Casterton and Little Casterton - were spaced only a few miles apart from Stamford and each other.

Peck suspected all these towns had been part of a much larger complex of Roman suburbs roughly centred on Stamford 4.

A third gap hints at more deception about when the events that created these ruins might really have occurred.

Here's the conventional narrative:

From Nene Valley Pottery Distribution - NVAT:

The colour coated pottery and mortaria produced in the lower Nene Valley were widely traded across Britain from the mid-second to the end of the fourth centuries.

Yet the rediscovery of this pottery only began about the time Sutton Heath and Fen Causeway were being dug away. About the time the area's history seems to have been re-written.

From Nene Valley Pottery Assemblages NVAT:

The early examples of Nene Valley Roman pottery discovered by Artis in the 19th century were beautifully illustrated but leave many gaps in our knowledge. The vessels are lost, their precise origin is often undefined, and they were not comprehensively documented.

It's odd that wealthy local landlords didn't collect this stuff for their neo-classical stately homes, leaving traces of it in itineraries and later auction catalogues.

And it's odd that early finds were - just like nearby Roman roads - 'lost' and 'not comprehensively documented'. Odd because as pottery goes, the most common Nene Valley Ware is eye-catchingly impractical:

Beaker 41 was marketed to the steady-handed. Source: Nene Valley Pottery Assemblages - NVAT

According to Nene Valley Grey Ware - NVAT, tippy-toppy beakers like Beaker 41 are the most common form of Nene Valley cookware found.

Archaeologists helpfully photograph Nene Valley beakers next to actual usable kitchenware so people familiar with cooking, eating and drinking can see for themselves:

Usable crockery flanked by joke crockery. Source: Nene Valley Grey Ware - NVAT

Telegraph linesmen also joke about beakers.

From Glass Insulators - Beachcombing Magazine:

Imagine turning one of these babies up-side-down and drinking champagne out of them so you could fit in with the bigwigs?

Porcelain threadless insulators. Source: Glass Insulators Conducting fascination for over 100 years – Beachcombing Magazine

Or even with archaeologists.

Frederick and Stukeley's accounts put rediscovery of Roman remains at around 1736. At that time, Stukeley suggested, former Roman England was still remembered as it was being pulled down and dug up. Both Stukeley and Frederick suggested population centers were in the process of being quarried.

But neither describes artefacts from the intervening 1,400 years of England's busy history. Especially the Normans. Perhaps the carving of Castor's church dedication date to 1137 was no stonemason's mistake but a misguided attempt to plug the gap in Castor's history.

Instead, slightly more detail about what might have really happened comes from studies of the iron works to the north of Stukeley's 'extended carcase of a large town'.

In 1997, archaeologist Frances Condron described the curious features of Roman iron smelting furnaces found at Thornhaugh and Sacrewell - less than a mile west of Sutton Heath and Sibburton.

It was a long paragraph so I've extracted only the essential parts. You can read the original in Part 2 of Iron Production in Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire in Antiquity in Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 71. Vol 71, pp. 1-20:

several bowl and shaft furnaces were built over demolished out-buildings. The excavator suggested that these belonged to a post-abandonment phase, though earlier finds of 18 furnaces may show longer-term interests in smelting or forging (though these remain undated),

That's a lot of Roman iron smelting furnaces (and the count is now over 26). They needed a lot of energy. Theoretically, that means they needed vast amounts of timber. Or perhaps those impractical beakers had something to do with it.

Condron continues:

At present, Sacrewell is unusual in the close association between dirty, polluting iron smelting and high-status residence, which favours interpreting the remains as a smelting and forging centre established over a newly abandoned villa.

Just so it's clear: Condron suspected the Sacrewell furnaces were attempts to build new smelters on top of a recently destroyed residential structures.

He wouldn't say it but I can: it sounds like people were trying to get the heat and lights back on after a natural disaster or a stunningly destructive war.

Today, Stukeley's ruined 'considerable town' around Sibburton is presented as one smelting complex a couple of miles south of a patchwork of Roman ironworks and quarries extending over 20 km (15 miles):

Iron smelting complex south of Stamford.

Key:

- Red line: Ermine Street

- Yellow circle: Centred on Stukeley's destroyed 'considerable town'

- Orange circle: Centred on Frederick's cinder-strewn Roman remains

- Grey circle: Large scale iron smelting site (allegedly Roman)

- Red circle: Condron's iron smelting complex at Thornhaugh/Sacrewell

The evidence - and gaps in the evidence - suggest the events covered by Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt folklore involved much more than removal of Holy Roman suburbs. They involved the removal of specific individuals and technologies.

Part two will show how other Wild Hunt locations in England are sited amid more signs of large-scale destruction.

Part three will look at a possible candidate for the Wild Hunt's innocent victim and female demon.

Part four will look at a bystander rescued from the destruction and one example of a removed technology.

More:

- Wild Huntsman Legends

- Dartmoor Wild Hunt and 'kennel' locations

- Northern Wild Hunt folklore - the Gabriel Hounds

- Legends of Sir Francis Drake

- Penance, Power, and Pursuit: On the Trail of the Wild Hunt by Ari Berk and Willliam Spytma

- "Into the Woods" series, 53: the Wild Hunt

- Wisht Hounds Part 1 - Wistman's Wood

- Wisht Hounds Part 2 - Abbot's Way & Richard Cabell

- Wisht Hounds Part 3 - The Dewerstone

For more evidence of a late-Holocene terraforming of the fens, see:

- Eloi Was South Holland, Lincolnshire

- On the Level About Lincolnshire - Part One

- On the Level About Lincolnshire - Part Two

- On the Level About Lincolnshire - Part Three

- Depopulated England. Eyewitness Evidence

-

Bronze Age houses uncovered in Cambridgeshire are Britain's 'Pompeii' Note the anomalous glass beads... They are only anomalous if the barrio they were found in has been mis-dated.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

The natural history of Northampton-shire, John Morton, 1712, p 510 and Historical Legends of Northamptonshire, Alfred Thomas Story, 1883, p 35. ↩

-

Peterborough's religious accounts also speculated the road was called Kinneburga's Way because the locals had forgotten Castor had been a "Roman city quite lost". However, John Morton's description of Castor's Roman remains on p509 of The natural history of Northampton-shire;makes it pretty clear that locals knew what remains they were living among. And Stukeley's account suggests they were still pulling down its ruins down 1737. ↩

-

They mean 'd' for 'died' not 'b' for 'born'. ↩

-

In Academia tertia Anglicana; or, the antiquarian annals of Stanford in Lincoln, Rutland, and Northampton shires. Containing the history of the university, monasteries, gilds, churches, chapels, hospitals and schools there ... in XIV books, Francis Peck, (allegedly) published 1727, p15 ↩

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis: Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt,

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis