Potsherds blow the whistle on a lost mass transit system. Wed 06 December 2023

Wild Hunt folklore went off the rails. Source: Cambridgeshire Coprolite publications

In Somerset Wild Hunt folklore, Gwyn ap Nudd worked at Glastonbury Tor. There he waited for deliveries of fresh Wild Hunt kills.

Gwyn ap Nudd seems to be the Somerset name for Nuada - a Wild Hunt leader with a thing for corpses.

From The Wild Hunt: A Midwinter Tale:

Arthur and his knights are said to ride over the hill fort at South Cadbury, (Cadbury Castle) in Somerset and down through the ancient gateway where their horses drink at a spring beside Sutton Montis church.

Below the hill are traces of an old track running towards Glastonbury, called Arthur's Causeway or Hunting Path

The causeway, also known as King Arthur's Hunting Path, links the hill fort at South Cadbury directly to Glastonbury Tor in a straight line, 11 miles distant. Glastonbury Tor is the abode of that other well-known “conductor of souls to the place of the dead”, and leader of the Wild Hunt, Gwyn ap Nudd.

In addition to writing Nudd/Nuada's job description, Somerset's Wild Hunt folklore provides a time-stamp.

From The Wild Hunt:

As late as the 19th century, rumors persisted that a king and his hunting party could be heard riding near Cadbury Castle on winter nights.

If you were searching for traces of an old track, King Arthur's Causeway direct to Glastonbury Tor, you'd probably explore along the red line below:

King Arthur's Cadbury Castle-Glastonbury wild hunt route.

Key:

- Red line: Folkloric wild hunt route

- Grey line: Possible route based on current roads

- Yellow line: Possible missing link

There are no obvious clues to a direct route between Cadbury Castle and Glastonbury Tor today. The grey and yellow alternative route shown on the map seems a more likely location for King Arthur's hunts and Gwyn ap Nudd's soul supplies.

Yet clues from other English towns show how King Arthur's now vanished causeway may have disappeared and how it was transformed into Wild Hunt folklore. Two of those clues lie beneath Lincoln and Oxford.

From High Street, Lincoln - Wikipedia:

The Roman road passed through low-lying wetland by the River Witham on a causeway.

In Roman times the river was much wider

The once wider river's former banks and the causeway that crossed it left underground traces of their grand-scale engineering.

From A Sketch Illustrative of the Minster and Antiquities of the City of Lincoln, Howlett Bartholemew, 1835, describing - on p59 - the northern bank of that older, wider River Witham, now under the northern end of Lincoln High Street:

In sinking a well at this part in 1826, at 8 yards deep, there was found the remains of the ancient wall, having an arched culvert, or sewer, of large size, with a level deposit of clean sea-sand and shells, beneath the arch.

The 'culvert or sewer of large size' in the bank of an apparent estuary is evidence of wetland civil engineering 200m north of today's River Witham.

The tourist-attracting bridge over today's River Witham seems to have been downsized:

Five arches reduced to one. High Bridge, Lincoln. Source

From The history of Lincoln - containing an account of the antiquities, edifices, trade, and customs of that ancient city - an introductory sketch of the county, author unknown, 1816, p149:

The High-bridge. A tradition exists that this bridge had no less than five arches, to cross as many channels of the river. It has now only one, twenty-one feet nine inches diameter, and eleven feet high, is at least four hundred years old. Many old houses remain on and about the bridge, which appear to have been religious buildings. It has this year (1815) been widened, and has received other improvements, which are a great accommodation to the public.

It's' easy to miss the comment that the bridge was 'widened' in 1815. The bridge was widened westwards - on the side away from the camera. The half-timbered 'medieval' coffee shop visible in the photograph sits on the section added in 1815.

Knowing the bridge was narrower before 1815 may help with grasping the timeline and scope of Lincoln's re-engineering. And Oxford's, St Ives' and probably many other English cities.

The mile-long stretch of Lincoln High Street south of High Bridge was a causeway. It was the top end of the Roman Fosse Way from Exeter. This ancient Norman-looking building was built on top of it:

St Mary's Guildhall, Lincoln High Street. Source: Roman ruins in Lincoln

From Roman Ruins in Lincoln:

A section of the original Fosse Way can be seen under protective glass in the foundations of St Mary’s Guildhall.

The Fosse Way remains [now] under St Mary’s Guildhall once formed part of the road’s northernmost section, just before it met Ermine Street south of the old city walls.

Like the High Bridge, Lincoln's High Street causeway was also buried and widened. Somehow, enormous amounts of material became available on site. Then they were added to the road's western side.

What we don't know is when Lincoln's 'ancient' stone heritage was built on top of its ancient causeway. But it seems likely High Bridge was was widened at the same time the road was widened. So the original Fosse Way was probably buried, then built upon, at the turn of the 19th century. Some time around 1800-1815.

Yet there is no record of who did the work or who funded the work.

While Lincoln buried causeway is hard to visualise, Oxford's buried causeways are - occasionally - easy to see:

Causeway found beneath Abingdon Road. 2004. Source: Medieval Grandpont and South Oxford

The stone-work in the foreground right is the top of an arch. But it too raises questions about massive, unrecorded urban engineering. And where the material around it came from.

Just like Lincoln's High Street, Oxford's Abingdon Road was originally a narrow, arched causeway crossing a much wider river.

Using the guy in PPE and a white hat as a six foot-tall guide, you can see the causeway is only about six feet (2m) wide. Not so obvious is just how much rubble and dirt has been piled (or has magically appeared) on both sides of the original causeway. And this is just one of Oxford's three lost causeways.

From Oxford Topography: An Essay, Herbert Hurst, 1833, describing Oxford's Abingdon Road on p13:

we come upon an embanked road, which was formerly a road raised on arches. This south road into Oxford, the east road and the west, all had these arched roads in former days

The two or three open arches of Magdalen Bridge will prove far inferior, for the purpose of carrying off floods, to the old Estbrugge with its twenty-five arches. On the south or Hincksey road, and on the west just beyond Oseny Bridge, embankments conceal the rows of arches

25 arches reduced to three. Magdalen Bridge, east Oxford. Source: Magdalen Bridge - Wikipedia

A trivial note is that he said 'Estbrugge' - East Bridge - as though in 1833, German words were still used for some Oxford place-names. And he didn't say the arched causeways were dismantled. He said they were concealed by embankments.

Where did the embankment material come from? When? Who did it and who funded it?

To appreciate just how much civil re-engineering is buried beneath those embankments, use Abingdon Road as an example:

From Oxford Topography: An Essay, p14:

Miles Windsor (Bal. p. 65, containing Wood’s notes) describes the Great South Bridge as extending 1,000 paces, probably 2,000 feet, on more than forty arches.

He seems the first to mention the number of arches

Hurst also quotes Leonard Hutten, who claimed the Great South Bridge - or Grandpont - was built on more than 40 arches before it was 'embanked'. That is - before its arches were filled in, the sides built out and the road above it widened.

40 arches reduced to three. Folly Bridge, south Oxford. Source: Folly Bridge and Folly Island

All by men with shovels and wheelbarrows.

What was possible around Oxford was possible around Lincoln. And it was possible around Glastonbury. Perhaps the noise and lights of mechanical equipment used for 'embanking' at this scale is what became the Wild Hunt folklore between Cadbury and Glastonbury.

For another sense of the scope of near magical building work that took place at individual sites, consider St Ives causeway in Cambridgeshire.

From St. Ives Bridge, Cambridgeshire: 15th Century Gem:

South of the bridge, the London Road proceeded across a swampy area on a causeway with piecemeal bridges built by various benefactors, from time to time and as the currents of the water shifted.

the causeway was totally rebuilt and opened in 1822.

With an astonishing 55 arches, it is the longest road causeway - as well as having the largest number of brick arches - in the country.

So St Ives was rebuilt shortly after Oxford's causeways were being embanked. And presumably around the same time as Lincoln's and Cadbury/Glastonbury's causeways were reworked.

Somehow a lot of civil engineering skills, labour, building materials and river control skills arrived in England in a very short space of time. Along with a lot of material from which to create new embankments.

Knowing large infrastructure has literally been covered up may help explain Wild Hunt folklore around Noke in Oxfordshire.

Again from Parishes: Noke - Victoria County History:

In the late 17th century [historian John] Plot found traces of what he took to be a Roman road running south from Noke to Drunshill, but this cannot now be located with certainty.

Well, not with certainty but crop marks help:

Parallel crop marks between Noke and Drunshill. Source: Google Maps

The avenue of trees near the top of the image is an above-ground clue to Plot's Noke-Drunshill line. Extrapolated south they become the parallel-line crop mark heading south to Prattle Wood. Extrapolated out of frame to the south, the lines pass very close to the clump of trees that now marks Drunshill.

And to the north?

Again from Parishes: Noke - Victoria County History:

In 1492 'Osyat Brugge' in Noke was said to be broken 'in uno se archs' [sic]. This structure may have carried the Greenway over the Ray towards Oddington.

That may mean Osyat Brugge was broken in one arch or in each of its arches. Either way Plot's Roman 'road' - the Greenway - could no longer cross the River Ray on its way north from Noke to Oddington.

Reading Parishes: Noke - Victoria County History, I would guess its author knew very well the nature and scale of the destruction they were hinting at. But again, we can't tell if Noke's Wild Hunt folklore describes former usage of the Greenway or its destruction.

What was it about causeways that caused them to be destroyed, 'embanked' into wider roads and the transformations hidden?

One clue lies in the peculiar English word for vehicles that carry people across rivers and sea channels:

'Ferry'.

'Ferry' doesn't seem related to any English word for river or sea transport. It doesn't seem related to words like 'ship', 'boat', 'punt' or even 'raft'. 'Ferry' is closer to 'ferrous' and 'farrier'. Words that relate to iron. Perhaps this helps explain why 19th century writers chose odd words to describe Roman roads.

From Romano-British remains: Roads:

Two metalled highways traversed Oxfordshire during the Roman period.

Of these roads, the Akeman Street, connecting two pre-Roman capitals, Verulamium and Corinium, may well have been an older track, metalled by the Romans.

Helpfully, we can still find 'ferries' working on the causeways of a remote outpost of the Holy Roman Empire. On the low-lying, flood-prone islands of Hallig Oland:

She's found the Hallig Grail. Source: Germans and Their Trains: A Love Story

Claudia said they used sails.

So did 18th century diarist John Byng.

On the 12 July 1791, he was travelling southbound along Ermine Street towards Stamford, Lincolnshire.

From The Torrington Diaries Vol. 2, Selection from Tours of John Byng (later Viscount Torrington) 1781-94, John Byng, edited by C Bruyn Andrews, 1935, p406:

thro' BrigCasterton, a pretty village, and mounting the hill above it, we spread all our canvas, and successfully, as to reach Stamford, (just as the storm fell,) and shelter in the gateway of the George Inn;

Byng is saying they spread all their canvas to climb the hill between BrigCasterton - now Great Casterton - and Stamford. Highlighted in orange below:

Ermine Street from BrigCasterton to The George Inn.

Key:

- Red marker: BrigCasterton (Great Casterton)

- Blue marker: Stamford

- Orange line: Byng's sailed stretch of Ermine Street

- Blue line: Ermine Street's old route through Stamford and branch to The George Inn

Their canvas helped carry them up a steady 4-5% gradient. While they may have been kite-surfing, the fact Byng carried baggage, canvas and presumably rigging suggests they were on wheeled vehicles. Presumably wheeled vehicles on tracks, as Claudia said.

On the map, the road curves away. But the original road over the top of that hill can be seen in the photograph between pages 192 and 193 or Roman roads in Britain vol.1: South of the foss way-bristol channel, Ivan D Margary, 1955. Along with its intriguing caption.

Through The Torrington Diaries, Byng often notes the wind direction before he set out and mentions how the weather helped or hindered his travels during the day.

From The Torrington Diaries Containing the Tours Through England and Wales of the Hon. John Byng Between The Years 1781 and 1794, Vol III, John Byng, edited by C Bruyn Andrews,1936, in a diary entry about a rainy day in June 1792 at Masham, North Yorkshire, p53:

I loiter'd for some time, thro' fear; but go I must; so I held down my head, but dared not to ride very fast over the pebbles: however I spread what canvas I could; and turning to the right cross'd the river Eure by horse-bridge

Crossing the River Eure from Masham would have put him in Low Burton, the site 40 years later of Masham's railway station.

Byng also refers to changing 'cars', 'curricles', 'chairs' and 'carriages'. If his cars, curricles and carriages ran on railed rural aggers, then Rome's logic-defying roads become more logical.

Such as along this well-preserved Roman agger:

They're banking upon your in-curiousity. Source: The Mystery Roman Object - that Defies Logic

Let's take another look at the top:

Carts and chariots travelling in opposite directions would struggle to pass each other on that narrow top. And any wrong move would have them sliding down its sides. Unless something kept them on track.

Add back this Roman road's less well preserved parts. Starting with a couple of soldiers on pest control duty:

Men obsess over battle tactics. Source: Stranger Things

Now we're back on track.

John Byng complained how difficult it was to use draft animals after causeways were 'improved'. In the following quote, a 'ramping' is Lincolnshire dialect for a causeway; 'turnpiked' means 'turned into a toll road'.

From The Torrington Diaries Vol. 2, Selection from Tours of John Byng (later Viscount Torrington) 1781-94, John Byng, Ed. C Bruyn Andrews, 1935 , in a journal entry dated 12 July 1791 near Riby, Lincolnshire, p390:

A rocky road, (here call'd a ramping road,) of a turnpike turn, led to Laceby, a pretty village, then thro' a variety of cross lanes, (leaving Riby village to our left,) wherein much trouble of driving was required, because our cattle are blundering upon bearing reins, (things not to be endured one moment); in a curricle every bump may overset you, it is a carriage of incessant care;

Byng also hinted that Roman infrastructure had made earlier vehicles easier to steer:

whereas in my old Italian chair, the horse chose his way, I loll'd in the corner, observ'd the country, and had my chat; now in the curricle it is an eternal looking to helm, & sail.

Photographs still exist of the descendants of Italian chairs, their occupants observing the country and having their chat:

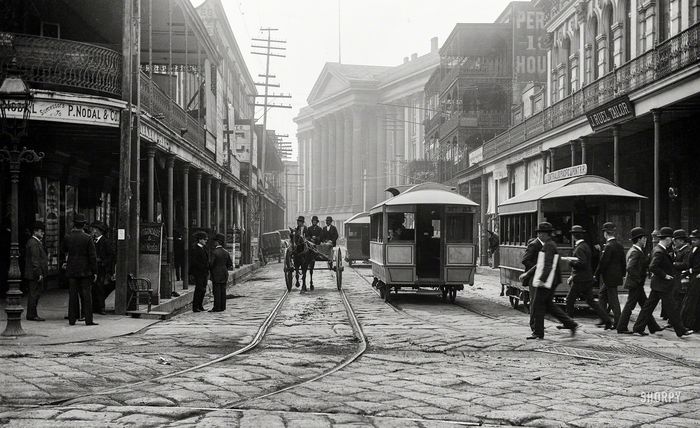

While their horse chose his way. Source: St. Charles Hotel from Canal Street - Library of Congress via 19th century: Russian Cast Iron Road

Those Holy Roman rails photographed in New Orleans look like plateway. Any narrow-wheeled vehicle can use it - so that specially cast flanged wheels are unnecessary:

And it's tough enough for quarry work. Source: History of the railway track - Wikipedia

Evidence of trams in tiny rural towns and villages suggests these small settlements were once interconnected by mass transit:

Source: Trolley-Forbidden Old-World Transit

These tracks were designed for trams, trolley cars, streetcars and ordinary carts to use. Their well drained, low friction iron rails hugely increased the distances even horse-drawn carts could travel.

From [History of the railway track - Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_railway_track:

The system found wide adoption in Britain.

Not just in towns and quarries:

Oopart agger crosses field at Folkingham, Lincolnshire.

Today, the road veers sharply away from this agger, hinting that the agger once continued as the direct route out of Folkingham.

Today it also appears to peter out after crossing the field:

But it continues as cropmarks across the countryside for a mile or so towards Threekingham's Acre Lane (Agger Lane). As it does, it weaves into and away from other linear cropmarks. They are reminiscent of John Byng's 'cross-ways'.

Their routes are easy to trace on a map:

Cropmark tracks visible between Folkingham and Northbeck.

Key:

- Orange line: Folkingham agger

- Blue lines: Linear cropmarks sometimes visible in Google maps

Extrapolated further north east, the cropmarks seem to head towards Northbeck's packhorse bridge:

All aboard for Scredington! Source: Packhorse bridge at Northbeck

That photograph plays down how Northbeck's packhorse bridge lines up with older 'roads':

It's another greenway. Source: Google Maps

From Packhorse bridge at Northbeck:

Known locally as Roman Bridge.

Did rural plateways once offer mass rural transport?

Did they have names like Green Lane and Greenway?

Make up your own mind. Source: Hallig Nordstrandischmoor, Lorenbahn

On Hallig Oland, they still use a wide range of curricles, cars and carriages.

You can still see their Dandy Dog eyes:

If you look at their roofs. Source: Lorenbahn Dagebüll-Oland-Langeness

More:

Side-saddle through Hallig Oland. Source: Hallig Nordstrandischmoor, Lorenbahn

In , Side-saddle through England in the Time of William and Mary.

Source: Lorenbahn Dagebüll-Oland-Langeness

Source: Inselbahn Schmalspurbahn Dagebüll Oland Langeneß Halliglore Lore 4

Source: Inselbahn Schmalspurbahn Dagebüll Oland Langeneß Halliglore Lore 12

Source: Inselbahn Schmalspurbahn Dagebüll Oland Langeneß Halliglore Lore 1

- Folly Bridge and Folly Island (Oxford). Note how the easy-to-remember illustrations underplay the number arches in the causeway compared to the number earlier visitor recorded.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis: Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt,

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis