A new angle on star forts Fri 24 March 2023

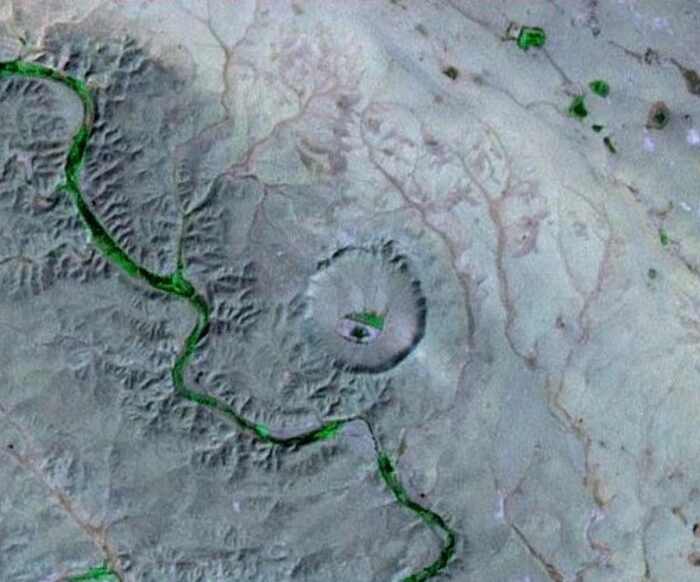

Amguid Crater, Algeria. Source: Meteorite Amguid - Argelia

Apparently, a river ran by it.

For scale, Amguid Crater (Google Maps) in Tamanrasset, Algeria, is roughly 500m (1,700ft) wide.

Aerial imagery suggests several of Africa's 20 acknowledged meteorite impacts also landed close to rivers:

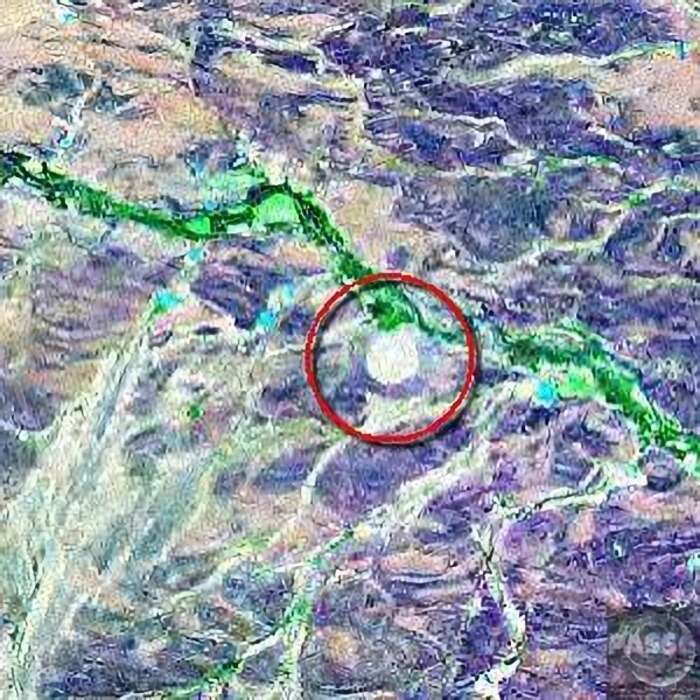

Talemzane Crater, Algeria. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa.

Talemzane Crater: Google Maps is roughly 1.7km (one mile) wide.

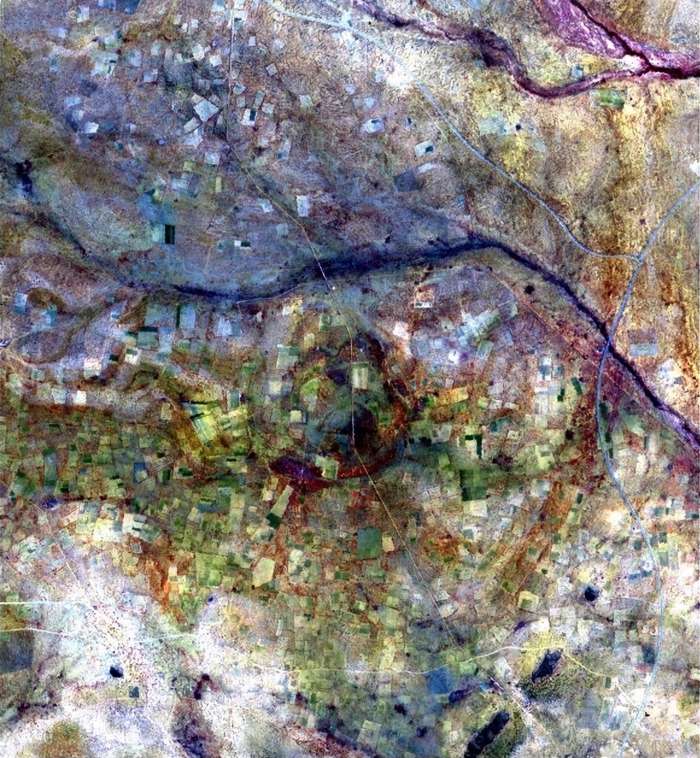

Kalkkop Crater, South Africa. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

Kalkkop Crater (Google Maps) is roughly 650m (half a mile) wide.

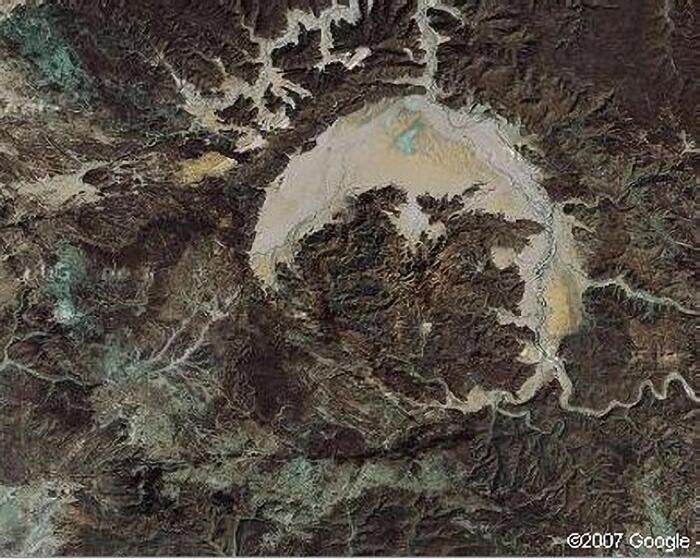

Kgagodi Basin, Botswana. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa.

Kgagodi Basin (Google Maps) is roughly 3.5km (two miles) wide.

Tswaing Crater, South Africa. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

Tswaing Crater (Google Maps) is roughly 1.13km (two thirds of a mile) wide.

Aerial imagery also suggests some meteorites landed close to meandering rivers and peculiar, linear landforms:

Gogui Crater, Raïchakh, Mauritania. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

Gogui Crater (Google Maps) is roughly 550m (1,800ft) wide.

Note the meandering landform (digitally processed to red and apparently disrupted near Gogui Crater) and the strange shaped landform superimposed upon it at upper right.

Traces of two parallel linear landforms reach towards the edge of the massive Gweni Fada Crater in Chad. They're visible on the left of the image below:

Gweni Fada Crater, Chad. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

Gweni Fada Crater (Google Maps) is roughly 14km (8.7 miles) wide.

These patterns - craters consistently appearing near meandering and linear features - suggest something more systematic than random cosmic impacts. But to investigate what we're really looking at, we need to step back and ask: what else on Earth creates circular or precise geometric structures near to meandering rivers and linear landforms?

Having examined the African evidence, let’s now compare it to structures found elsewhere in the world—specifically, the star forts of Europe and beyond. These military installations share striking similarities with the craters we’ve discussed, from their geometric precision to their proximity to waterways.

Kalah i Daráb, Darabjerb, Iran. Google Maps

Kalah i Daráb (Google Maps) is almost 1.9km (over one mile) wide.

Westerners know this destruction site as the Citadel of Darius. We're told it's the remains of a fortified town once protected by a 10m (33ft) high circular earthwork.

At its centre, rock peaks resemble the central uplift sometimes found in meteorite craters:

Kalah's inconvenient town centre. Source: Hidden and little known places Darabgerd, Iran

No records survive of Kalah's original, enormous construction project. Nor of its destruction.

Except for a curious detail of folklore.

From The Ancient Round City Of Darabgard:

sources suggest that Dara, either an Achaemenid king or one of the Frataraka “maker of fire” or “keeper of fire” rulers of Arsacid Persis, could be the founder of the city

That detail is reminiscent of the creation story of Henbury Crater in Australia.

From Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve - Wikipedia:

... older Aboriginal people would not camp within a couple of miles of the Henbury craters. An elder Aboriginal man ... claimed his paternal grandfather had seen the fire-devil and that he came from the Sun. An Aboriginal contact said of the crater field: tjintu waru tjinka yapu tjinka kurdaitcha kuka, which roughly translates in the Luritja language as "A fiery devil ran down from the Sun and made his home in the Earth. He will burn and eat any bad blackfellows."

It's off-topic just here but catch the recency in Aboriginal account: "his paternal grandfather". Traces of recency nestle like ticks in the folklore of various African and Middle Eastern meteorite sites.

However, their recency is for another time. We were looking for clues that might explain why meteorite craters seem to show up close to watercourses and unnatural-seeming linear landforms.

Across Europe and beyond, military engineers once built fortified settlements with remarkably similar characteristics to certain African meteorite craters: geometrically precise shapes, circular and polygonal layouts and strategically positioned near rivers:

Citadel of Alessandria, Italy. Source: What Do Star Forts Look Like From Space

Sometimes a river runs between a pair of star forts:

Terezin, Czechia. Source: What Do Star Forts Look Like From Space

Star fort architecture might also explain the nature of the "target terrains" RF Fudali and Philip J Cressy noted at three African craters.

In their 1976 paper, Investigation of a New Stony Meteorite from Mauritania with Some Additional Data on its Find Site: Aouelloul Crater, they contrasted the "perfect circle" of Tenoumer Crater with the polygonal rims of Aouelloul Crater and Temimichat Craters.

What components of star forts might present polygonal "target terrains" strong enough to deform the crater left by a meteorite strike?

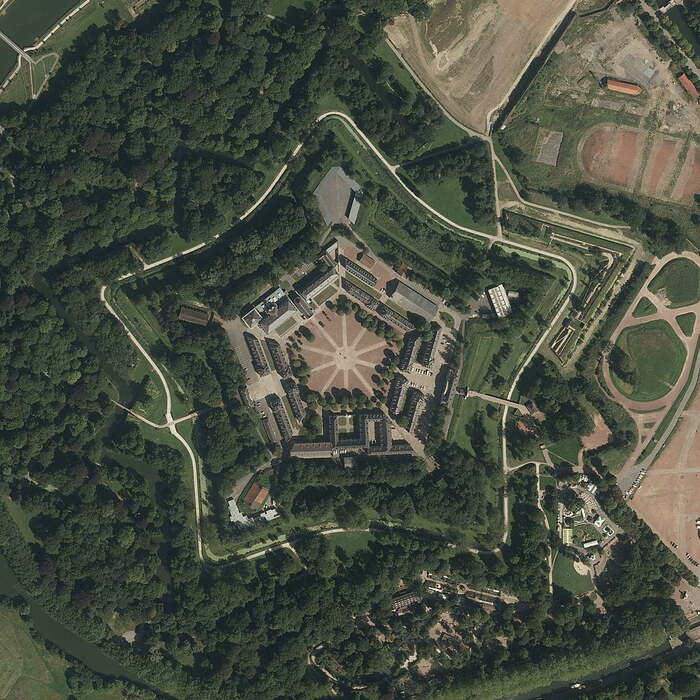

Naarden, The Netherlands. Source: Most Impressive Star Forts Around The World

Originally filled with water, the moats of the best preserved starforts (AKA bastion forts) are dry today:

Palmanova, Italy. Source: Most Impressive Star Forts Around The World

Note Palmanova's central, hexagonal "target terrain".

Here's another hexagonal "target terrain":

Almeida starfort, Portugal. Source: What Do Star Forts Look Like From Space

And here's a pentagonal "target terrain":

Citadel of Lille, France. Source: Star Forts - Complex Geometry of the Post-Medieval Era

Polygonal shapes at the centre of star forts are the remains of thick, earth embankments faced with stone:

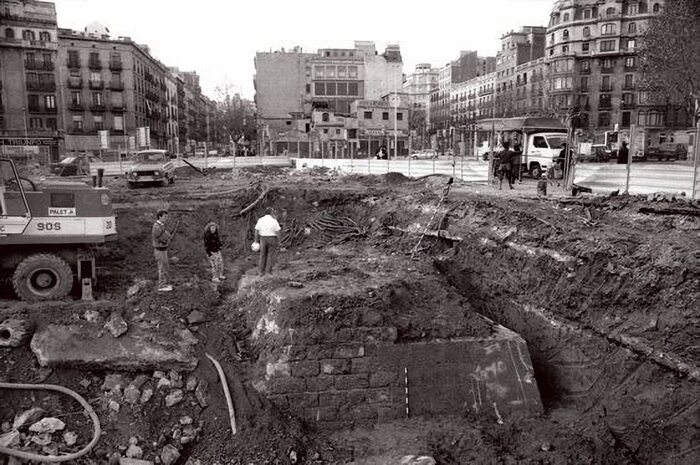

Barcelona's underground embarrassment. Source: Barcelona. Ancient buildings covered with 8 meters of soil

They're called curtain walls. They offer strength in all the right places.

Just not from above.

If we assume that some craters are remnants of star forts, then the following sequence of events could explain their polygonal shapes: a plasma event destroys the structure, causing walls to collapse and slump into moats, followed by demolition and quarrying that leaves behind subtle traces of the original geometry.

The Barcelona photograph hints at a little-known truth: more of these structures were destroyed or buried than survive today. In England, for example, both Oxford and Cambridge sit on top of star forts whose buried outlines few could now find. Even as they walk on top of them.

Oxford's extended beyond the modern town's centre:

Simplified plan of Oxford star fort. Source: Mapping The English Civil War

This plan shows just the outer edge of Oxford's ramparts. Earlier plans show its curtain walls were much thicker.

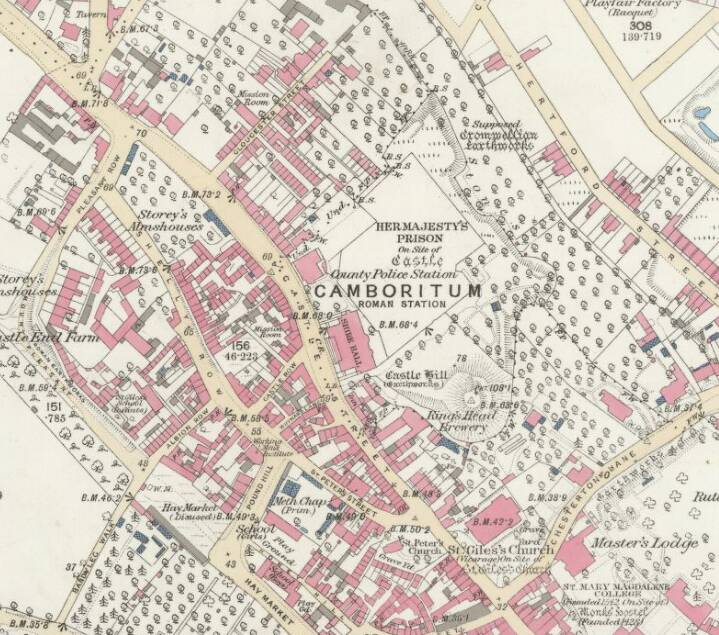

In Cambridge - or actually, beneath Cambridge - part of a star fort is buried east of Huntingdon Road beneath Cambridgeshire council's offices and the castle:

Star fort remains beneath north west Cambridge. Source: Cambrito - NLS

Cambridge star fort may have been paired with a second similar structure buried about six kilometres (four miles) away. Excavation on the site is forbidden but if so, it too was buried, but marled with chalk and over-planted with trees. A rural mystery finally over-planted with real and fake folklore.

Seemingly early in the 19th century, a great deal of effort went into burying star forts and star fort remnants. Along with a great deal of earth-moving. It required unimaginable volumes of soil.

That's what it took to cover this part of Barcelona star fort:

A cover-up uncovered. Source: Barcelona. Ancient buildings covered with 8 meters of soil

This high quality bridge and road construction was revealed during 1950s roadworks.

The result:

You get the point? Source: Barcelona. Ancient buildings covered with 8 meters of soil

The point is: the authorities know what to do about star forts.

Some polygonal "target terrains", however, survived. As long as they weren't in Africa:

Leopoldov, Slovakia. Source: What do Star Forts Look Like From Space?

Spit fort, Klaipėda, Lithuania. Source: Spit Fort

Fort Carroll, United States. Source: Carroll Fort

Many polygonal "target terrains" outside of Africa were apparently damaged and subsequently repaired:

Fort Jefferson, Florida. Source: Time After Time

Fort Jefferson where, as the narrator points out, the different upper brickwork suggests an older stone structure has been refurbished.

Many African impact structures are so enigmatic, scientists can't agree narratives that fit their strangeness. The resulting contortions generate bizarre continuity errors. Continuity errors like the crater line across Mauritania, where the craters were first considered to be meteoritic, then volcanic, and now three of them are considered meteoritic and the remainder volcanic.

And continuity errors like the narrative of Libya's Arkenu Craters:

Can you connect the dots? Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

Scientists once thought Arkenu craters were meteoritic. Today, scientists think both are volcanic.

Note the trace of a polygon to the right of the upper crater.

If you see other evidence in that photograph of other straight edges near the craters, then, well, quite.

For scale, they are 9 km (six miles) apart.

Explaining Arkenu Craters would require less contortion if scientists considered the possibility they were once a pair of star forts. Such as these two:

Petrovaradin, Serbia. Source: What Do Star Forts Look Like From Space

And if they considered the possibility that Arkenu Craters' creation story followed this sequence:

flowchart TD %% Original Structure A[Original Starfort Structure or Settlement: Polygonal Walls, Moats, Structures] -->|1. Plasma Event|B[Destruction Phase: Shock, Slumping, Collapse, Melting, Vitrification] %% Combined Demolition/Quarrying Phase B -->|2. Secondary Demolition/Quarrying| C[Removal of Usable Material] %% Resulting Crater C --> D[Resulting Crater: Shallow, Debris-Free, Hexagonal/Polygonal Traces] D --> F[Geology: Traces of Blast Damage, High-Temperature Minerals, No Meteorite] D --> G[Archaeology: None Found] %% Styling style A fill:#98FB98,stroke:#333 style B fill:#FFA500,stroke:#333 style C fill:#ADD8E6,stroke:#333 style D fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 style F fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 style G fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 linkStyle 0 stroke:#FFA500,stroke-width:2px linkStyle 1 stroke:#ADD8E6,stroke-width:2px

From star fort to science enigma

See also Fingerprints of the Clean Up Team.

Some craters are so bizarre, scientists seem too embarrassed to label them 'a crater':

Luizi Impact Structure, Democratic Republic of Congo. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

One possible reason Luizi was converted into the Luizi Impact Structure becomes apparent when Luizi is compared with Tilbury in Essex, England:

Tilbury's target terrain. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

If some African craters are the remains of destroyed forts or settlements, we should also find around them the remains of people. Or the remains of people's ways of dealing with the remains of people.

Before we explore this, be familiar with desert realities. Carrying the dead in, out and around deserts isn't usually practicable. So bodies - sometimes fossilised - are occasionally found where their owners died:

Note the location name: Ghallaouiya. Source: Ep. 3/4 HUMAN SQUELETON IN SAHARA - Ghallaouiya / Tichit, largest expanse of sand in Mauritania

That's from near Temimichat crater, Mauritania. How about the remains of people at Temimichat's neighbouring craters?

From Aouelloul Crater - Wondermondo:

In the rims of the crater are several ancient tombs.

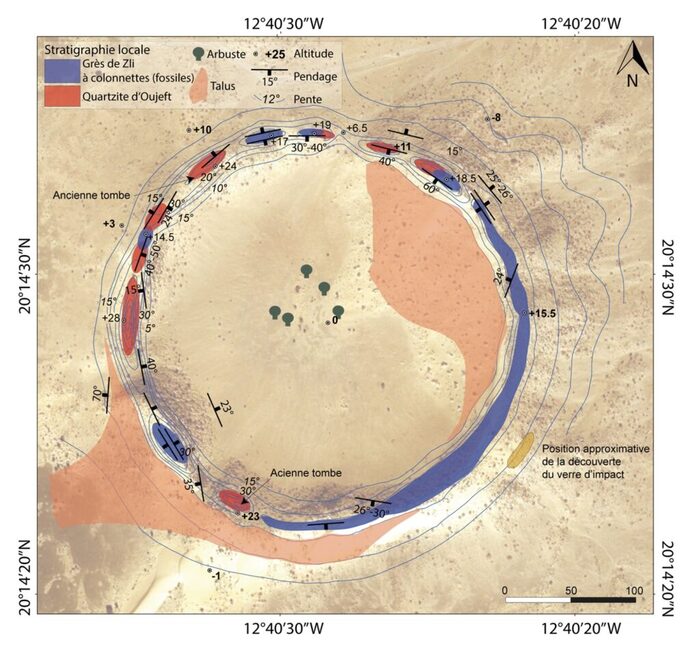

Visitors have described the area immediately south of Aouelloul's crater rim as two graveyards. This map locates tombs in both the southern and north western sections of the crater rim:

Aouelloul's tombs. Source: La cratère d’Aouelloul : sur les traces de Théodore Monod

Aouelloul is so remote it is unlikely that anyone would build tombs or graveyards there. Or even allocate camel teams to haul bodies to them. More likely, members of a community died here and were interred where they died.

And by the way, none of this explains the glass shown on the map as a yellow patch south east of Aouelloul's crater rim. Glass that was chemically more like Darwin Glass from Tasmania than local glass made by impact-melted Saharan sand. Explaining that glass requires extra contortion.

This pattern of meteorite craters being shaped by the target terrains they struck becomes even clearer when we examine the folklore surrounding desert destruction events. Local traditions don't describe random cosmic accidents; they describe the deliberate destruction of communities. Often they describe the specific targeting of communities that had become corrupt or defiant.

Aouelloul Crater has already been mentioned as a candidate for the disappeared town of 'Fulli' and a blast that destroyed a town of bad people.

If we head north east from Aouelloul Crater across the Sahara Desert to Wabar Crater in Saudi Arabia, we pass Tall el-Hammam in Jordan. It's sometimes presented as a candidate site for Sodom.

From Discovering Earth Impacts:

The first known impact to have taken place during human history obliterated the ancient town of Tall el-Hammam, in what is now Jordan

Excavations at Tall el-Hammam began in 2005, with archaeologists quickly realizing that something disastrous had happened to the town, with buildings smashed, the inhabitants blasted apart, and intense heat scorching the area.

Closer examination was that the damage indicated intense heat, with melted rocks and metal artifacts -- which wouldn't have happened if the town had simply burned down.

Continuing towards Saudi Arabia we pass Tell Abu Hureyra in Syria.

From Fire in the Sky: Cosmic Impact Obliterated Prehistoric Settlement:

The glass [excavated at Tell Abu Hureyra, Syria] was analyzed for geochemical composition, shape, structure, formation temperature, magnetic characteristics and water content. Results from the analysis showed that it formed at very high temperatures and included minerals rich in chromium, iron, nickel, sulfides, titanium and even platinum and iridium-rich melted iron -- all of which formed in temperatures higher than 2200 degrees Celsius.

Syria's wider landscape also suggests it was reformed by fire:

Ashes of a Syrian mega-town. Source: Lost Civilizations (Inconclusive Tour) Middle East Lands

He's looking at Daraa, north east of Izraa: Google Maps.

His "looks cooked out" area is the west edge of Masmiyeh: Google Maps. Here be clumps of cracked rocks and traces of derelict, Roman-straight roads.

The ruins he shows gradually being recovered are here: Google Maps

Syria contains many more cooked out areas but absence of people also means absence of explanatory folklore. So continuing eastwards to Wabar Craters in Saudi Arabia...

From Wabar Craters - Wikipedia:

In 1932, Harry St John "Jack" Philby was hunting for a city named Ubar, that the Quran describes being destroyed by God for defying the Prophet Hud. Philby transliterated the name of the city as Wabar.

Philby devoted much of account of Wabar's discovery to dismissing his guides' claims they were exploring the molten slag of a burned city. Expert vulcanologist that he wasn't (he was a former Foreign & Colonial Office administrator) he dreamed up a new explanation for the crater-riddled mass of blackened melt-rock that starts immediately east of Wabar's Craters.

From The Empty Quarter, H St John Philby, 1933, p165:

I reached the summit and in that moment fathomed the legend of Wabar. I looked down not upon the ruins of an ancient city but into the mouth of a volcano, whose twin craters, half filled with drifted sand, lay side by side surrounded by slag and lava outpoured from the bowels of the earth.

Philby's explanation for Wabar's black mass still perplexes visitors today.

From Google Maps:

I visited this place in 2004, it is very strange

As are several of the so-called 'volcanic' sites in Syria that we skipped over while following the folklore trail between Aouelloul to Wabar.

As is the fact that there is another crater (and possibly two) 30km (20 miles west of Wabar Crater).

Despite Philby's dismissive narrative, Arab folklore of targeted urban destruction does find support from an unexpected quarter: The Empty Quarter.

Wabar is deep inside the Empty Quarter. In Arabic 'The Empty Quarter' is Rub' Al Khali.

Khali.

Across multiple languages and continents, several of these locations share the 'Khali' phoneme. It suggests a common understanding of what happened in some of these places. Or perhaps even 'who' happened.

Temimichat - that peculiarly hexagonal Mauritanian crater - has a longer name: Temimichat Ghallaman. Or, depending who's talking, 'Temimichat-Ghallaouiya'.

Ghallaouiya is the location of the desert corpse found earlier. 'Ghallaman' and 'Ghallaouiya' are pronounced something like 'Halla-man' and 'Halla-weeyah' but with a harder 'H'. Somewhere between 'H' and 'K'. The bit that's common to both versions is 'Khalla'.

In Iran, we also saw the spectacular and unexplained Kalah i Daráb.

That's Kalah as in Kali and Cailleach. If you don't know who she is and her reputation for destruction, landscaping and climate change, do read Ice Age Sites of Britain's Serpents.

Kali/Cailleach's approach to landscaping is well known in parts of northern Europe.

From Kaali crater - Wikipedia:

Kaali is a group of nine meteorite craters in the village of Kaali on the Estonian island of Saaremaa.

It was created by an impact event and is one of the few impact events that has occurred in a populated area (other ones are: Henbury craters in Australia and Carancas crater in Peru).

That list rather adroitly leaves out impact events that occurred in populated areas and wiped out the population. Regardless, Estonia's Kaali event is thought to have created a high pillar of plasma that burned a two-mile wide fire zone. The Kaali event may account for the 'fire in a disastrous sky' imagery seen on some northern European coins:

The dates suggest early 17th century. Source: Jehovah vs The Star Cities

I mention that only because the very strange events around Kaali's main crater - too off-topic for here - also include 17th century cooked animal bones.

Oh Kali! What have you done?

Key:

- Fire marker: Individual Kaali crater impacts

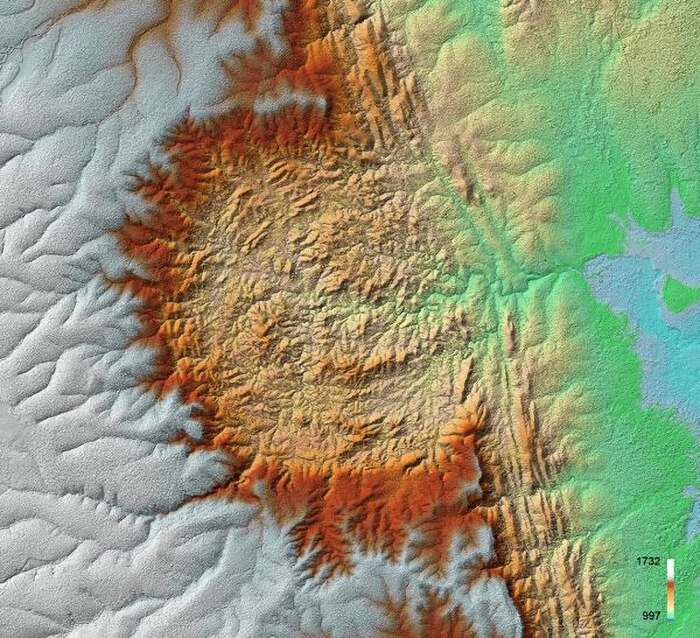

Whether they were aimed at settlements or were random acts of space, meteorite impacts struggle to explain how three huge craters acquired an outer ring:

Source: Sweden’s Siljan Ring

Source: Manicouagan Crater - NASA

Manicougan Crater and Aorounga Crater both acquired multiple rings:

Aorounga Crater, Chad. Source: Impact Craters on Earth - Africa

From Sweden’s Siljan Ring:

Surveys of the structure have shown that the ground is slightly raised up across parts of the crater’s center. It is surrounded by a ring-like graben, or depression, which today is partially filled with water.

From Manicouagan Crater - NASA:

it contains a 70 kilometer (40 mile) diameter annular lake, the Manicouagan Reservoir, surrounding an inner island plateau, René-Levasseur Island.

With their raised centre, their mysterious outer ring and the unknown mechanics of their origin, they present a creation mystery similar to the much smaller Kalah i Daráb.

However, a plausible alternative explanation for all bizarre crater shapes, their missing meteorites and their strange folklore is a variation on the same sequence of two events applied to large, pre-existing ring-shaped reservoirs.

- A plasma event that destroyed a structure or settlement at the 'impact' site. Then:

- A very large scale scavenging, demolition and quarrying event that removed usable or scrappable material from the ruins, leaving poorly explained rings, polygonal rims, relatively flat crater depths, strange folklore, and accounts of searches for missing meteorites, etc.

The inexplicable pentagons and hexagons in Mauritania's craters become explicable if the polygons are remainder artefacts of what was originally a starfort shape. In this sequence, the plasma event very severely damaged the original starfort structure, causing parts of it to collapse and other parts to slump into the large moats and water channels that formed its perimeter. Subsequent demolition/quarrying works left soft or subtle traces of these formerly clearly defined polygonal outlines.

A sequence like this:

flowchart TD %% Original Structure A[Massive Engineered Structure: Polygonal Walls, Moats, Star Fort Structures] -->|1. Plasma Event| B[Destruction Phase: Vitrification, Collapse, Slumping] %% Destruction Phase B -->|Extreme Heat| B1[Walls Melt or Vitrify] B -->|Shockwaves| B2[Collapse: Roofs Collapse, Walls Slump into Streets and Moats] %% Combined Demolition/Quarrying Phase B1 -->|Clean-Up Team| B3[Demolition/Quarrying of Remains] B2 -->|Clean-Up Team| B3 B3 --> C[Removal of Usable Material: Metal, Stone, Glass] %% Resulting Crater C --> D[Polygonal Crater Rim: Subtle Traces of Original Walls] C --> E[Structural Change: Moats Filled with Debris] C --> F[Geology: Missing Meteorites, Traces of Vitrified Stone, Unusual Glass] %% Evidence F --> G[Folklore: Divine Punishment, Fiery Devil, Fire from the Sky] E --> H[Archaeology: None, High-Temp Minerals, Rare Metals] %% Styling style A fill:#98FB98,stroke:#333 style B fill:#FFA500,stroke:#333 style B1 fill:#FFA500,stroke:#333 style B2 fill:#FFA500,stroke:#333 style B3 fill:#ADD8E6,stroke:#333 style C fill:#ADD8E6,stroke:#333 style D fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 style E fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 style F fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 style G fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 style H fill:#D3D3D3,stroke:#333 linkStyle 0,1,2 stroke:#FFA500,stroke-width:2px linkStyle 3,4,5,6,7,8 stroke:#ADD8E6,stroke-width:2px

How mis-labelled meteorite strikes leave polygonal crater rims, anomalous glass and no meteorite

Seems outrageous right?

I'm not sure it's more outrageous than the residents of Barcelona, Oxford, Cambridge unknowingly living their lives on top of the cleaned up remains of massive star forts.

And it would explain the location of Libyan Desert Glass and its enigmatic neighbours.

And - the 'bombarded star fort conjecture' - may also help us to get to the bottom of one of Earth's least publicised mysteries.

The very, very strange nature of its meteorites.

More:

- Darab - Wikipedia

- Dara (Mesopotamia) - Wikipedia

- The 2,500-plus-year-old Town Of Darabgerd In Southern Iran - Iran Front Page good for images of Citadel of Darius

- The Ancient Round City Of Darabgard Good for details of Darius

- Richat Structure (Eye of the Sahara) - Wikipedia

- Aouelloul Crater - Wikipedia

- Temimichat Crater - Wikipedia

- Tenoumer Crater - Wikipedia

- Chinguetti - Wikipedia

- The Age of Tenoumer Crater, Mauritania, Revisited

- La cratère d’Aouelloul : sur les traces de Théodore Monod

- Aouelloul Impact Crater, Mauritania: New Structural and Lithological Data

- Aouelloul Crater

- New Evidences of an Impact Origin for Temimichat Crater, Mauritania

- Exposure age, terrestrial age and pre-atmospheric radius of the Chinguetti mesosiderite: Not part of a much larger mass

- Aouelloul Crater - Wikipedia

- Temimichat Crater - Wikipedia

- Tenoumer Crater - Wikipedia

- The Fake History of Africa

- New evidence on the lost giant Chinguetti meteorite

- Seven Possible New Impact Structures in Western Africa Detected on Aster Imagery

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

More of this investigation:

Desert Forensics,

More of this investigation:

The Reformation Was a Reformatting,

More of this investigation:

Fingerprints of the Clean Up Team

More by tag:

#geology