Behold a cracked narrative. Wed 22 March 2023

Barringer Crater squares the circle. Source: Meteor Crater, Arizona, USA

America's most well-known meteorite crater has a curious shape:

And a cracking story. Source: 10 impact craters seen from space

Looking at the lower and right-hand corners, it resembles half of a hexagon.

Perhaps it was a hexagon before Standard Iron Company spent 30 years quarrying it for a single ten million ton chunk of iron.

From Daniel Barringer (geologist) - Wikipedia:

It was unable to find the meteorite, however.

I doubt that the little bay - the dimple - in the lower, straight edge of its rim is all that was dug out in 30 years of quarrying.

Over in the western Sahara, Mauritania's Temimichat Crater is also a curious shape:

Staring down the hexen. Source: Ep.2/4 IMMENSITY OF SAHARA - Aïn Ben Tili / Ghallaouiya, north Mauritania, 580 km no water point

From Théodore Andre Monod and the lost Fer de Dieu meteorite of Chinguetti, Mauritania, UB Marvin, 2007, p201:

Thus, of Monod’s five Mauritanian ‘cratériform accidents’, two were of impact origin and two were volcanic. That left the crater of Temimichat Ghallaman, with its dramatically hexagonal rim, c. 670 m across, the origins of which remain uncertain.

A dramatically hexagonal "crateriform accident" with uncertain origins is at sixes and sevens with the official narrative. That may be why we find attempts to explain away Temimichat's shape.

From New Evidences of an Impact Origin for Temimichat Crater, Mauritania:

its outline was described as hexagonal. We interpret this polygonal shape of the crater [as] derived from differential erosion of the rim.

That would be very geometrically-minded differential erosion then. And if you don't mind me saying, I think the video shows Temimichat Crater remains visibly hexagonal.

And that we're being rimmed.

In Mauritania's case, it is a double rimming.

From Investigation of a New Stony Meteorite from Mauritania with Some Additional Data on its Find Site: Aouelloul Crater, RF Fudali, Philip J Cressy, 1976, p267:

We note that both Aouelloul and Temimichat have polygonal rims, indicating the target terrains exhibited enough strength to control the crater shapes. Conversely, Tenoumer is almost perfectly circular, indicating the target rocks behaved as a low strength, homogeneous medium - presumably due solely to the greater impact energy expended.

'Target' is an interesting word and 'the target terrains exhibited enough strength to control the crater shapes' is an interesting phrase. But before trying unpack them, let's double-check that Aouelloul crater really is a polygonal "cratériform accident" and not your everyday circular "cratériform accident".

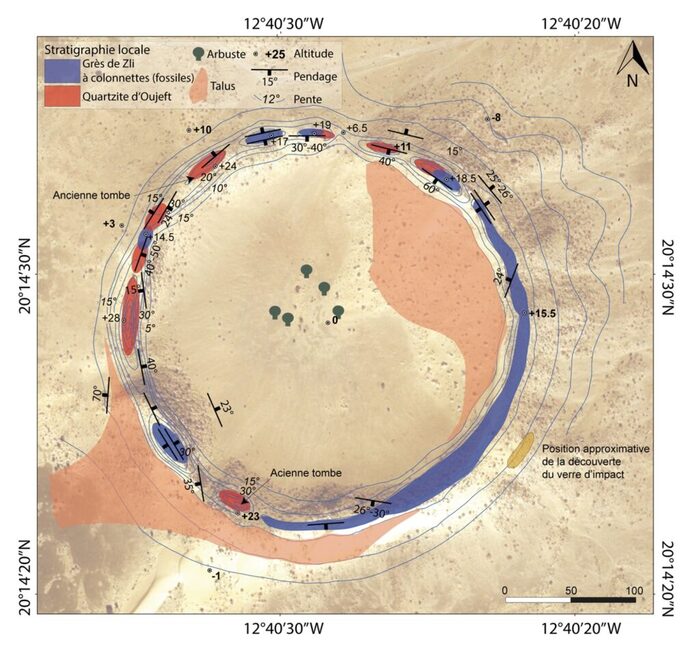

Here's a map of Aouelloul Crater, drawn to show the two rock types found along the crater's rim:

Quartzite in pink; sandstone in blue. Source: La cratère d’Aouelloul : sur les traces de Théodore Monod

Looks circular - more or less - to me.

And here's a satellite image of Aouelloul crater:

Another angle on Aouelloul. Source: Are the so-called impact craters in Mauritania kimberlite pipes?

Give it a good look.

The next image was taken from about 45o around to the west.

Yet another angle on Aouelloul. Source: Are the so-called impact craters in Mauritania kimberlite pipes?

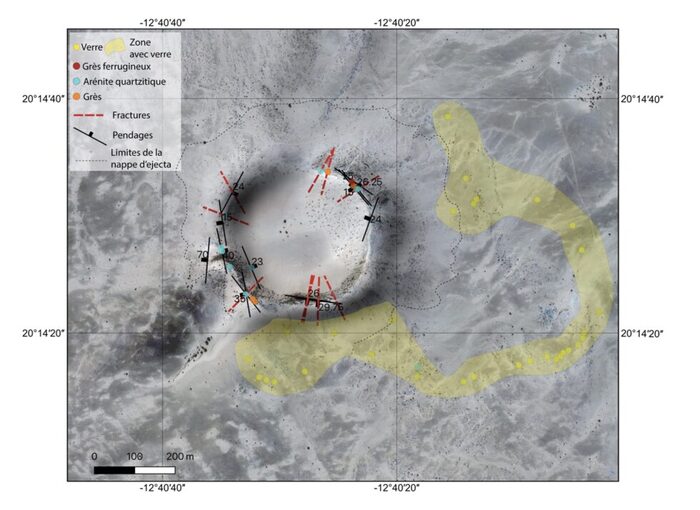

Here's another photograph of Aouelloul with a map overlay. The map was drawn to locate fused glass (yellow patch) and enigmatic cracks (red lines) around the crater rim:

Read between the lines. Source: La cratère d’Aouelloul : sur les traces de Théodore Monod

Aouelloul's rim is another cracking story. As its very peculiar fused glass.

Perhaps this last image - marked up by me - helps settle any questions about Aouelloul Crater's shape:

Based on image from Are the so-called impact craters in Mauritania kimberlite pipes?

That should raise questions.

Although you can't see it in satellite imagery, there's another dimension to Temimichat Crater's hexagonal shape.

It's curiously shallow.

From New Evidences of an Impact Origin for Temimichat Crater, Mauritania:

Gravity data indicate that the structure is shallower than what is expected for a simple crater of that size.

And it turns out its hexagonal partner Aouelloul crater is curiously shallow too.

From Investigation of a New Stony Meteorite from Mauritania with some additional data on its find site: Aouellel Crater, RF Fudali, Philip J Cressy, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Vol 30, Issue 2, 1976:

An additional (and perhaps related) peculiarity is that the negative gravity anomaly associated with the crater is most simply interpreted in terms of an unusually shallow original depth for an impact crater of Aouelloul's diameter. These features have led us to speculate elsewhere that there was something unusual about the projectile responsible for the crater.

The 'unusual projectile' that may have created Aouelloul Crater was once thought to be the enormous, missing 'Fer de Dieu' meteorite. In the 1920s and 1930s, one eyewitness account of this million ton iron set western specialists exploring this area. Back then it was called the 'Adrar Meteorite'.

The Adrar or Fer de Dieu's story is well summarised in The Meteorite that Vanished and in The World's Largest Meteorite Seemed to Vanish in 1916. Why Can't We Find It?.

Originally I was going to summarise it here. But I realised the utterly weird story was likely composed to draw attention away from other Mauritanian craters. I decided to analyse the method of distraction - but then realised the effort would distract from identifying what the distraction was attempting to hide. Which seems to be: the true nature and origin of these craters. So, for skeptical analyses of the many problems in every part of every version of the 'Adrar/Fer de Dieu' and Aouelloul Crater narratives, see:

- Théodore Andre Monod and the lost Fer de Dieu meteorite of Chinguetti, Mauritania, UB Marvin, 2007:

- The Adrar (Chinguetti) Meteorite, Mauritania, Lincoln Lapaz, Jean Lapaz, 1976

- NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) 19700032528: Physical chemistry of the Aouelloul crater glass, John A O'Keefe, 1970

Summarising very heavily, two of many problems around just one of these craters - Aouelloul - are its fused glass and its lone, tiny meteorite find.

1. Aouelloul's Fused Glass:

From Investigation of a New Stony Meteorite from Mauritania with some additional data on its find site: Aouellel Crater, RF Fudali, Philip J Cressy, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Vol 30, Issue 2, 1976, p262:

Compared to other terrestrial impactites the Aouelloul glass is unusual in several respects.

From NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) 19700032528: Physical chemistry of the Aouelloul crater glass, John A O'Keefe, 1970, Abstract p1:

The data do not support the hypothesis of impact origin for the Aouelloul glass.

From p5:

Campbell Smith and Hey showed that the composition of the glass is very much different from one kind of local sandstone, and resembles Darwin Glass.

The comparison of the Zli sandstone as analyzed by Chao, et al (1966a), with the Aouelloul glass shows a number of discrepancies.

Special explanations are available from these discrepancies

Reasons will be given below why neither of these explanations will work;

From p18:

Summing up, we may say that the production of glass of the composition of the Aouelloul crater glass from sandstone of the composition of the Zli sandstone... is impossible.

If I understood O'Keefe's insinuations correctly, he was hinting Aouelloul's fused glass matches glass from the other side of the planet (Tasmania) and had been manufactured to very high purity.

2. Aouelloul's Meteorite:

From Théodore Andre Monod and the lost Fer de Dieu meteorite of Chinguetti, Mauritania, UB Marvin, 2007, p201:

In 1973, Raleigh Drake, a member of a Smithsonian team searching for impactite fragments found a small, 76 g (3 oz) stony meteorite on the rim of the Aouelloul crater. His discovery was particularly surprising because the stone was mostly covered by a fusion crust that clearly distinguished it from all the [local] country rocks. Furthermore, the meteorite lay on the southeastern portion of the rim which already had been picked-over by searchers for glass fragments on their hands and knees. From the first, it seemed doubtful that the small stone could have been a fragment of the body that excavated the crater.

From Investigation of a New Stony Meteorite from Mauritania with Some Additional Data on its Find Site: Aouelloul Crater, RF Fudali, Philip J Cressy, 1976, p263:

it is somewhat surprising that it was not found long ago

and:

The meteorite's areal association with the impact crater is merely coincidental.

From all of which the following emerges:

- The Fer de Dieu story was likely developed as a distraction designed to firmly link several curious holes in the western Sahara with volcanoes and/or meteorites.

- That the evidence a meteorite created Aouelloul Crater relies solely on:

- the miraculous 1973 appearance of a small, mineralogically ill-fitting piece of meteorite on an already meticulously searched section of Aouelloul Crater's rim, and

- the miraculous discovery around the crater of fused glass that doesn't chemically resemble Aouelloul's local sand but which strongly resembles fused glass from Darwin Crater in Tasmania.

- That Aouelloul's glass - and therefore presumably Darwin Crater's glass - were originally created in highly controlled conditions - the type of conditions applied when manufacturing glass.

- That Aouelloul's structure and layout is incompatible with any (publicly known) crater formation process, volcanic or meteoric.

We're being rimmed again.

Though you will actually have to read the papers - and read them carefully - to appreciate why I say this.

If it's hard to believe someone is creating stories about giant meteorites creating giant craters and populating some of them with glass and iron sourced from elsewhere, then feel free to consider the opposing claim. That someone is creating stories that giant meteorite impacts don't create giant craters.

Or any crater.

Such as the Hoba Meteorite:

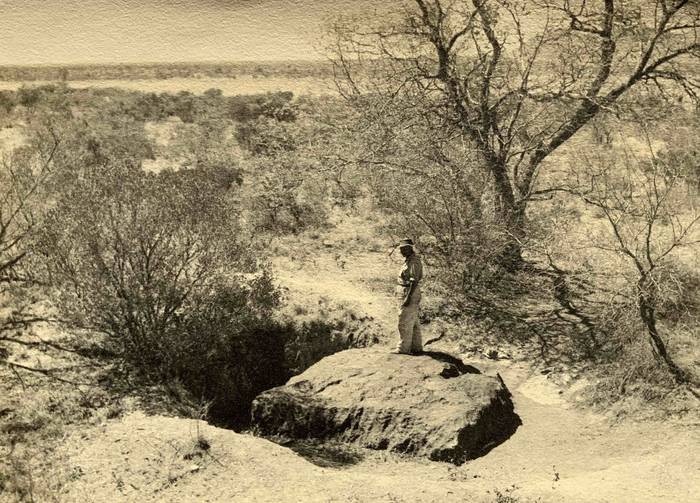

Hoba in its after-market crater. 2014. Source: Hoba meteorite - Wikipedia

This 61 tonne iron-nickel behemoth - the largest meteorite known to man - allegedly settled into the Namibian savanna at a sedate 6,140 mph - or Mach 8 - with barely a dent. Well actually, without any dent. It just sort of integrated itself onto a layer of limestone below a thin layer of Kalahari dust:

Hoba after a quick dig to assess its thickness. Early 1920s. Source: Hoba meteorite - Wikipedia

Apparently, the Hoba Meteorite entered Earth's atmosphere weighing 70 tons but lost nine of them to heat ablation and souvenir hunters.

Nevertheless, Hoba is the largest single piece of iron known to man. And its story is quite possibly the largest pile of bullshit narrated to man. Starting with the claim that its thorn tree-studded site was being ploughed when the curiously regular slab of ferronickel alloy was first discovered.

There's so much else wrong with the Hoba impact narrative, the various Hoba discovery narratives (see pages 87 and 89) and the subsequent Hoba management narrative that it feels insulting to set them out.

Yet Hoba is not alone in its pitiful craterlessness.

From The 'Barratta' Meteorite, Australia:

some time around 1845 unusual pieces of heavy stone were found on Barratta station, lying flat on the ground without any noticeable crater. The largest piece was reported to be about 76 cm in diameter and about 30 cm thick, and would have weighed about 100-150 kg (360 lbs).

And from Mundrabilla meteorite - Wikipedia:

In April 1966 two very large iron masses of 12.4 tonnes and 5.44 tonnes were found in the Nullarbor Plain at 30°47′S 127°33′E by geologists R.B. Wilson and A.M. Cooney during a geological survey. The two masses were lying 180 metres (590 ft) apart, in clayey soil within slight depressions. The masses were surrounded by a large number of small iron fragments. The meteorites were named Mundrabilla, while the largest fragment, the eleventh largest found in the world as of 2013, is distinguished as Mundrabilla I.

If hexagonal meteorite craters dent the official narrative, you should see the hole made in it by craterless impacts.

From Théodore Andre Monod and the lost Fer de Dieu meteorite of Chinguetti, Mauritania, UB Marvin, 2007:

scientists faced the conundrum posed by large iron meteorites that lay on the surface of the Earth with no associated craters.

How, then, was it possible to account for certain huge irons that showed no signs of having disrupted the landscape where they fell. There was the 31 ton Ahnighito iron that lay on the rocky west coast of Greenland with no sign of a crater when it was first seen in 1897 by Lt Robert H. Peary; and the 70 ton Hoba iron, first recognized as a meteorite in 1920, that lay on undisturbed ground in the desert of Namibia (SW Africa). In addition, there was the alleged million-ton iron in the Adrar desert near Chinguetti in Mauritania.

That last one is the missing 'Fer de Dieu' mentioned earlier.

The solution was simple, Marvin explained; scientists came up with a plausible explanation:

a huge iron could make a soft landing if it were to approach the Earth tangentially, at an angle of 1o or less, and follow a long trajectory until it decelerated to a terminal velocity of less than 1 km/sec

If you've ever been in a car crash, you too will appreciate how modern car paintwork stands up to being hit by a 61 ton chunk of fiery-hot iron decelerated to less than 3,600 km/hour. Though it still doesn't explain Hoba.

Marvin also highlighted one of several implausibilities about the explanation:

They said nothing about deep grooves it might make as it scoured its way across the ground.

Which circles around another problem with the meteorite crater narrative: there's no obvious reason why so many alleged meteorite craters are circular:

Source: 536 ad "The Worst Year in History" the Hidden Impact Event That Led to the "Dark Ages"

Well, two craters aren't circular and one looks like a squared off circle. And a few craters actually are elliptical:

Source: You Expect Me to Believe Rocks Float in Space?

That last one is the Middlesboro Crater in Kentucky. Note that it plays a role in a human migration and resettlement story - as did two areas of fused desert glass in Desert Forensics - Part One.

We're told Daniel Moreau Barringer was also very puzzled by Barringer Meteorite Crater's circularity. He believed - it is alleged - that a 10,000,000 ton iron meteorite had descended at an angle and buried itself below Barringer Meteor Crater's southern rim.

From Unique History: A Crater Is Born:

All previous explorations of the crater had been based on the assumption that the meteorite struck from directly above. Barringer, however, began to test that assumption by firing rifles into mud at various angles, and discovered that a projectile traveling at an oblique angle at high velocity would nevertheless create a round hole.

The scientific method at its best.

Presumably, Barringer tested the theory because he couldn't find a meteorite anywhere in Barringer Meteorite Crater. Perhaps he should have looked have looked in the spoil that seems to have been carted away. But then again, perhaps he did.

Anyway, all we have left to explain is hexagonal craters.

And at least three ring craters:

Some craters run rings round logic. Source: 10 impact craters seen from space

That's Manicouagan Crater.

Aorounga Crater, northern Chad. Source: 10 impact craters seen from space

This next one is called Siljan - pronounced "Silly 'Un":

Siljan Crater, southern Sweden. Source: 10 impact craters seen from space

It's probably called that for a reason.

We are confronted by big meteorites without craters and big craters without meteorites. And big craters that are oddly shallow and big craters with rings. By big craters that look like trigonometry exercises. And by big craters arranged in lines where one or more of them weren't created by the same event.

Plus glass where it shouldn't be, a pocket-sized meteorite where it hadn't previously been.

And with iron meteorites that aren't iron but high quality ferronickel alloy and stone meteorites that are aren't 'stone' - but we will come to both of those.

If we actually read the skeptical links provided and understand that you have to bend both chemistry and rationality to get, say, Aouelloul Crater to be a meteorite crater, then what else might explain these holes - and rings - in the ground?

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

More of this investigation:

Desert Forensics,

More of this investigation:

The Reformation Was a Reformatting

More by tag:

#geology, #enigmatic landscaping