Impact sites aren't what they used to be. Tue 21 March 2023

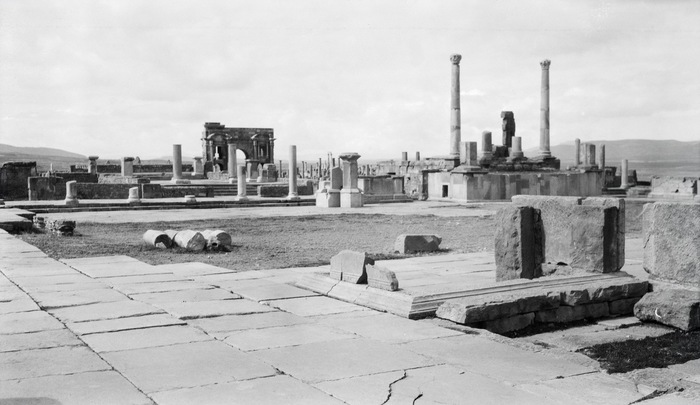

The sun set on Timgad. Source: Timgad - Wikipedia

From Timgad - Wikipedia:

At the time of its founding, the area surrounding the city was a fertile agricultural area

This quote attempts to link Timgad's rise with a narrative that claims the Sahara cycles between aridity and fertility.

From Sahara - Wikipedia:

For several hundred thousand years, the Sahara has alternated between desert and savanna grassland in a 20,000-year cycle

Unfortunately, Timgad is a poor fit for the '20,000-year Saharan fertility cycle' narrative.

From Timgad - Wikipedia (and summarised and clarified):

The Romans founded Timgad in AD 100. But with the 5th Century AD (meaning: after 400 AD) collapse of the Roman Empire, Timgad was repeatedly looted. It was finally abandoned in the 8th Century AD (meaning: 700 AD or later).

The Timgad narrative claims that when Timgad was re-discovered 1,000 years later, the Sahara had become the arid desert we know today.

If Timgad was founded by the Western Roman Empire, the Sahara transitioned from fertile-to-arid in about 2,000 years. Five times faster than the Saharan fertility cycle narrative claims.

If Timgad was founded by the Eastern Roman Empire (AKA the Byzantine Empire), the Sahara transitioned from fertile-to-arid in about 1,500 years. Seven times faster than the narrative claims.

If Timgad was founded by the Holy Roman Empire (Holy Roman Empire), the Sahara transitioned from fertile-to-arid in about 1,000 years. Ten times faster than the narrative claims.

Something seems awry.

But what? Are there other clues?

One clue is this from Sahara - Wikipedia:

For several hundred thousand years, the Sahara has alternated...

Which suggests some event occurred several hundred thousand years ago. What event?

From Sahara - Wikipedia:

One theory for the formation of the Sahara is that the monsoon in Northern Africa was weakened because of glaciation during the Quaternary period, starting two or three million years ago. Another theory is that the monsoon was weakened when the ancient Tethys Sea dried up during the Tortonian period around 7 million years ago.

So they are blaming glaciation for weakening African monsoon. But they can't agree on when.

This matters because the various 'age-of-the-Sahara' narratives and the Sahara 'fertility cycle' narrative can't be reconciled with the the Libyan desert glass narrative.

From How a Meteor Crash Formed Stunning Desert Glass:

"About 20 million years ago, either a meteor impact or atmospheric explosion got to the desert part of the lower atmosphere, heated it up and fragmented and exploded,” she says. “It dumped a huge amount of heat, like in thousands of Fahrenheit degrees, into that portion of the desert, which was a relatively pure deposit of quartz sand."

In this theory, the Sahara already existed when Libyan desert glass was created about 20 million years ago. And therefore Libyan desert glass has decorated Saharan sand for about 20 million years.

But if the Sahara cycles from fertile to arid and back to fertile every 20,000 years, then Libyan desert glass is hardly likely to still be lying on its surface.

If the Sahara formed at least 20 million years ago then the theory of aridity-fertility cycles is nonsense. The glass would have disappeared by now.

For the same reason, if the Sahara formed only seven million years ago then the theory of aridity-fertility cycles is nonsense.

For the same reason, if the Sahara formed only three million years ago then the theory of aridity-fertility cycles is nonsense.

And if the Sahara only started its aridity-fertility cycle "several hundred thousand years ago" then the 20 million year old Libyan desert glass theory is nonsense.

Either the Sahara doesn't cycle; or Libyan desert glass has magic resurfacing properties. Or Libyan desert glass is much younger than 20 million years. Or any one or two or all of those three.

But problems with the Timgad narrative give us a clue to how old the Sahara might really be.

Paraphrasing Timgad - Wikipedia again:

After discovering Timgad in 1765, explorer James Bruce brought it to Western attention in his 1790 book Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile.

Well done if you noticed the 25-year gap between discovery and publication. Clearly, Bruce wasn't desperate to cash in on his discovery or to raise public funds to continue exploring the enormous Roman site.

Another 'well done' if you added 1,000 years... to Timgad's '8th century abandonment' and found yourself wondering if Bruce's 18th century discovery of Timgad came just a few years after it was abandoned.

Bruce's account intrigued 19th century Robert Lambert Playfair, who popped over in about 1877 and found there was even more to Timgad. On the hills outside of it.

From Timgad - Wikipedia:

These hills are covered with countless numbers of the most interesting mega-lithic remains.

Sounds like the Timgad area had been fertile enough to support a lot of manual labourers and their labours.

Fifty years passed between Playfair's visit and the following photographs taken in 1928. In that time, the vast Timgad site was, as Wikipedia puts it, "systematically excavated":

Or systematically cleaned out. 1928. Source: Timgad - Wikipedia

Note the little weeds in the near foreground. There is no high contrast with the soil so the surrounding soil is probably not sand. And there is no debris trapped among the ruins. It really has been swept clean.

Timgad's cleaners had even tidied the lawn:

Perhaps it's just dark raked sand. Source: Timgad - Wikipedia

With that tidy square and with its streets neatly laid out Roman grid-style, Timgad is reminiscent of small-town America - after the American Civil War.

This last photograph is titled "Exhibition Buildings in Timgad":

Note the windows, roofs and chimneys. Source: Timgad - Wikipedia

You have to wonder for which visitors this level of cleaning, tidying and rebuilding was thought worthwhile. But perhaps it wasn't worthwhile. Perhaps this level of cleaning, tidying and re-building were collateral benefits of five decades spent scouring Timgad's ruins for artefacts. And sifting out the interesting finds.

Clearly, there is more to Timgad than meets the eye.

And there is much more to the Sahara than meets the eye:

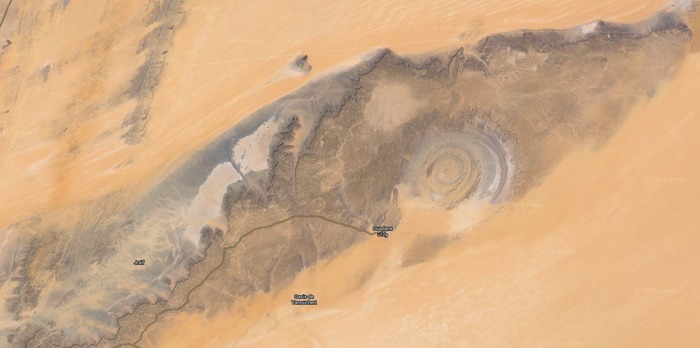

Er Richât - the Eye of the Sahara. Source: Google Maps

The blue is fake. A photo-processing technique to show areas with high salt levels. When you see the Richât Structure in its natural colours, it's looks like every other 40 km (30 mile) wide desert anomaly:

A 40 km (30 mile) wide desert anomaly. Source: Are the so-called impact craters in Mauritania kimberlite pipes?

Er Richât is a big brown stain on Saharan narratives.

With a little companion:

Although little Semsiyat isn't so little. Source: Are the so-called impact craters in Mauritania kimberlite pipes?

At 5 km (3 miles) wide, Semsiyat is big by 'normal' crater standards. It only looks little when compared to its enormous neighbour 50 km (30 miles) to the north east.

Neither structure contains as much crushed rock or shatter-cones as a meteorite crater so both structures are described as 'of terrestrial origin'.

And that works. As long as you ignore their companions.

From Richat Structure (Eye of the Sahara) - Wikipedia:

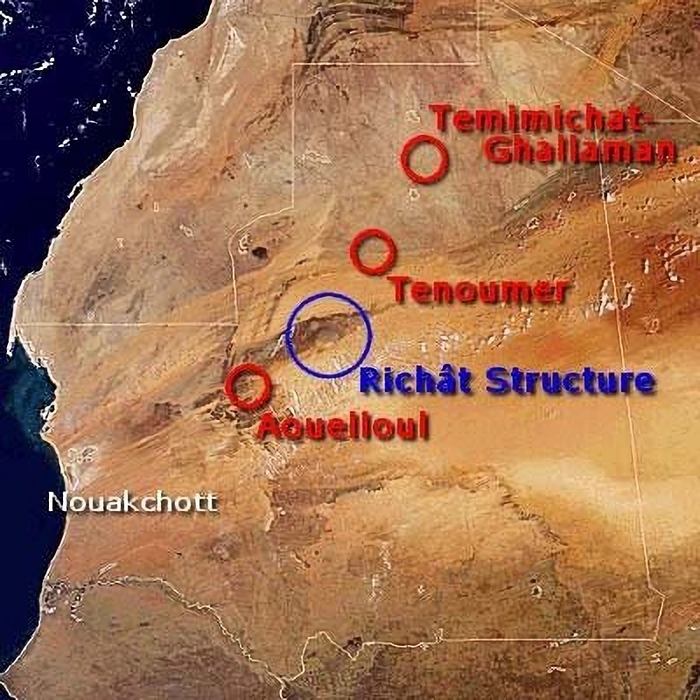

A geological expedition to Mauritania led by Théodore Monod in 1952 recorded four "crateriform or circular irregularities" in the area, Er Richât, Aouelloul (south of Chinguetti), Temimichat-Ghallaman and Tenoumer.

Monod later added Semsiyat, bringing his list of craters to five.

Their french discoverers had an amusing euphemism for the three "crateriform or circular irregularities" either side of Er Richât.

This is the Aouelloul "crateriform accident":

Diameter: 390 m. Source: Aouelloul Crater - Wikipedia

This is the Temimichat "crateriform accident":

Diameter: 700 m. Source: Are the so-called impact craters in Mauritania kimberlite pipes?

And this is the Tenoumer "crateriform accident":

Diameter: 1,800 m. Source: Tenoumer Crater - Wikipedia

You can probably see why some people thought the Richât Structure was another "crateriform accident" in the meteorite crater style.

From Richat Structure (Eye of the Sahara) - Wikipedia:

It was initially considered to be an impact structure (as is clearly the case with the other three), but a closer study in the 1950s to 1960s suggested that it might instead have been formed by terrestrial processes.

Note that says:

suggested and might

What are they dancing around?

From Investigation of a New Stony Meteorite from Mauritania with Some Additional Data on its Find Site: Aouelloul Crater, RF Fudali, Philip J Cressy, p266:

Aouelloul crater is almost perfectly aligned with two other Mauritanian craters - Tenoumer (1800 m in diameter), a proven impact crater and Temimichat Ghallaman (700 m in diameter), a probable impact crater . The straight line joining these craters extends over 600 km. Meteorites impacting planetary surfaces randomly do not normally create non-random alignments

That's very delicately put. Aouelloul crater is almost perfectly aligned with Tenoumer and Temimichat.

But not as perfectly aligned with them as Er Richât is:

A 600 km long coincidence. Source: Eyes of the Sahara

Astronomers call this 'a crater line'.

Earth scientists call it 'a coincidence'.

Earth scientists have subsequently tried to make the coincidence go away by claiming one or more of the craters were caused by various types of magma burp. And by dating Mauritania's line-loving craters to different events occurring in different eras.

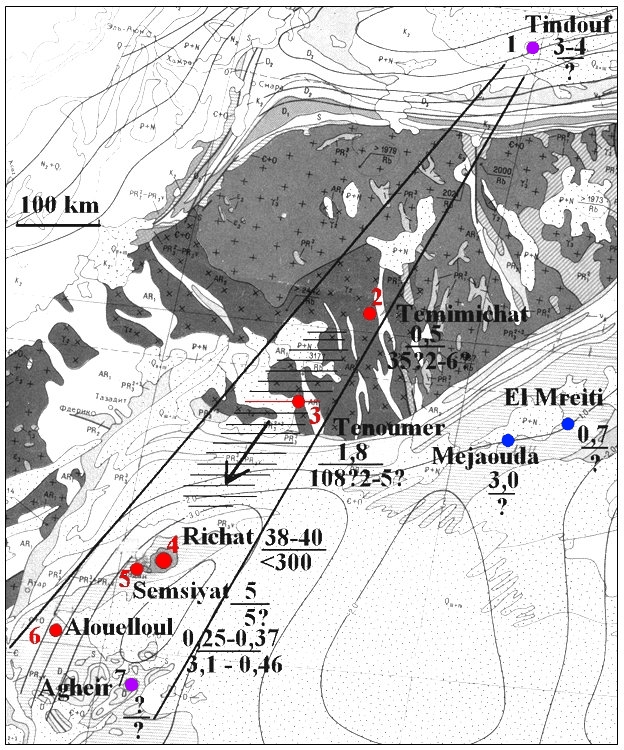

Unfortunately for scientists, motorcyclists also pay close attention to holes in the ground. And Saharan motorcyclists have also mapped Mauritania's craters:

The seven potholes of wisdom. Eyes of the Sahara

Key:

- Red dots: Theodore Monod's five west Saharan craters

- Purple dots: Adds two craters within west Saharan crater cone

- Blue dots: Undiscussed craters east of Tenoumer Crater

Saharan motorcyclists say:

- The craters you've mentioned (coloured red on the map above) fall - or fell - in a narrow cone rather than a line.

- The cone's apex is at Ourkziz Crater (coloured purple), near Tindouf in Algeria (formerly 'Tindouf Crater').

- The cone expands as you ride 208 deg south west from Ourkziz Crater.

- After passing Aouelloul Crater you pass Agheir Crater (also coloured purple).

- If you have the fuel and water, you may want to divert eastwards and check out El Mreiti and Mejaouda craters.

- Not far from El Mreiti Crater is El Mrayer Crater, though we didn't include it on our Potholes of Mauritania map.

If you want to ride the line, someone helpfully created this zoomable map of it on Google Maps.

A destruction cone that starts at Ourkziz Crater is a destruction cone that has been near Timgad:

Locations of west Saharan craters.

Key:

- Red marker: Well-known craters

- Blue marker: Less well-known craters in line with Er Richât

- Yellow marker: Less well-known craters in line with Er Richât and Semsiyat

- Black marker: Chinguetti

Which reminds us we were looking for clues that help explain why Timgad's "Roman and 1,600 years old" narrative doesn't reconcile with the Sahara's 20,000 year fertility cycle narrative. And why the age of Libyan desert glass doesn't reconcile with any of the many 'Age of the Sahara' narratives.

Here's Mauritania as mapped in (allegedly) 1630:

Per Willem Janszoon Blaeu. 1630. Source: [Virtual Map Collection]https://www.chartae-antiquae.cz/en/globes/78916)

The red circles are my guesses for - listing them from top to bottom - the relative locations of Temimchat, Tenoumer, Er Richât and Aouelloul. Er Richât seemingly being covered by three animals fighting.

Blaeu's 1630 map (actually a globe) is revealing. Note the text over what is now a crater-rich part of Mauritania. The text details which settlements were at that time depopulated and which were still partially occupied.

And Blaeu's map may tell us more about Aouelloul. That it's a crater because something kicked the 'F' out of a town called Fulli.

Source: The 100 Meter Meteorite That Just Disappeared | Fer de Dieu of Chinguetti | Spark

Unfortunately, the mosque is in Chinguetti and so this tale seems to refer to an cratering event east of that town. While Fulli/Aouelloul is 40 km south west of Chinguetti.

The mystery of what happened south east and south west of Chinguetti is what led the french military, surveyors and specialists from other countries to be criss-crossing this part of Africa finding "crateriform accidents". The ostensible reason they were there is very well covered in popular accounts. It's what their story distracts from that is of real interest so that's next up for examination.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

More of this investigation:

Desert Forensics,

More of this investigation:

The Reformation Was a Reformatting

More by tag:

#geology