Margaret Beaufort is the saint of lost plots. Thu 07 December 2023

Margaret Beaufort: pallid saint of lost property. Source: Lady Margaret Beaufort - Wikipedia

Before inspecting the overgrown stretch of Ermine Street between Stamford and Roman Durobrivis (now Castor), William Stukeley detoured to Collyweston:

William Stukeley's September 1737 itinerary

Key:

- Red marker: Collyweston

- Blue marker: Stamford

- Blue line: Ermine Street

From The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, M. D., Vol III, William Stukeley, published 1887, p56:

We saw ... the Royal Palace of Harry VII's mother, Margaret, Countess of Richmond.

He means Collyweston Palace.

This Collyweston Palace:

- Amateur historians discover long-lost Tudor palace, The Telegraph, 2023-11-20

- Tudor palace used by Henry VIII is FOUND after 500 years, The Daily Mail, 2023-12-04

- History fans find Collyweston royal palace 'against all odds', BBC, 2023-12-05

- Long-Lost Tudor Palace Discovered by 'A Bunch Of Amateurs', All That's Interesting, 2023-12-06

- Legendary, long-lost palace discovered near Stamford by historical society, Peterborough Today, 2023-12-22:

And from Collyweston - Wikipedia:

The building was dismantled in about 1640, leaving little trace. Its location was not definitely known until 2023, when ground-penetrating radar confirmed its location and found the main cluster of buildings, and footings of its walls were unearthed.

Lucky Stukeley. A century after Collyweston Palace was demolished, he did know where it had been. He even thought the site worth the detour.

40 years after Stukeley, visitors still knew the location of Collyweston's long-lost palace.

From Collyweston - Victoria County History:

a few fragments of the earlier building were still recognizable in 1776 (Nichols, Literary Anecdotes, VIII, 621–2)

And 200 years later, they still knew:

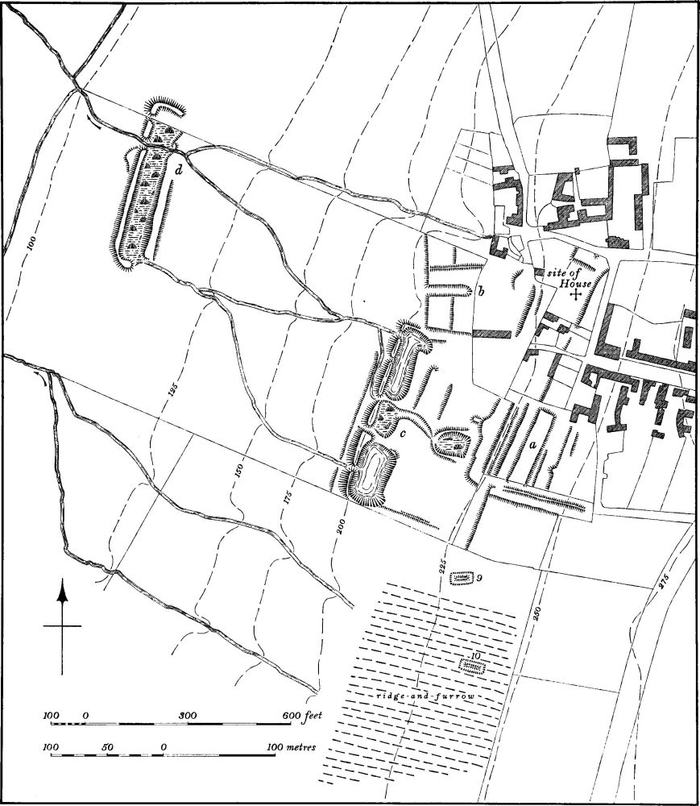

X marks the spot. Source: Collyweston - Victoria County History

Or rather '+' marks the spot. Along with the label on the right that says 'site of House'.

The map was drawn from aerial survey imagery. According to Collyweston - Victoria County History, the site of the long-lost palace was photographed between 1939 and 1945.

So in four out of the five centuries during which the palace was allegedly lost, its location was not only known but documented.

Something like this:

| Date | Century | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1640 | 17th | Palace allegedly dismantled and location lost |

| 1737 | 18th | Palace visited by Stukeley |

| 1776 | 18th | 'Recognizable fragments' reported |

| 1887 | 19th | Book footnote cites memory of building by 'person still living' |

| 1939-1945 | 20th | Surveyed by air and mapped |

| 2019 | 21st | Location 're-discovered' |

These and many other anomalies in Collyweston's narrative suggest the palace was never lost. Instead, its 'long-lost' narrative feeds suspicion that its location was only 'forgotten' in public and not in private.

Why might that be?

From Collyweston - Victoria County History:

[Robert] Heath's main intention was to dismantle the house, the materials of which were valued at £1000, and this he did in 1640

So Margaret's soon-to-be-demolished house had salvage value. Sufficient value that its owner and his plans were known and being documented just as England descended into the chaos of the Civil War.

From Currency converter 1270–2017 - National Archives:

Year of currency: 1640 Value of currency: Pounds: 1000

In 2017, this was worth approximately: £117,546.00

It would be double that now.

You would think buyers would generate new documentation about the site's location as potential and actual buyers inspected, bought and collected Heath's salvage.

Similarly, records should have been created when Heath subsequently sold - or rented - the site to John Tyron.

From The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, M. D., Vol III, William Stukeley, in a footnote to Stukeley's entry of 1737-09-10 on p56:

The palace stood where Mr. Tyron’s stack-yard is. A great hall, tower, dungeon, and kitchen with four chimneys, were standing within the memory of a person still living, but now the very ruins are themselves destroyed.

It's not clear when this revealing footnote was added to Stukeley's text. Perhaps in 1737. Perhaps by the editor of the 1887 edition in which the footnote is now found. Regardless, the footnote tells us that in 1737, or perhaps as late as 1887, someone 'still living' was able to describe how Collyweston Palace looked before it was demolished.

If Heath had completely demolished the palace in 1640, then 'a person still-living' who remembered it 93 years later must have been a very long-lived 'person still-living'.

Perhaps the site took longer to dismantle than we're told.

From A Lost Royal Palace in England Linked to Henry VIII Discovered by ‘A Bunch of Amateurs’:

Mr. Close said Collyweston Palace, also known as Collyweston House, would have been “made up of a large network of buildings situated to the west of High Street.” He referred to historical records which say the palace measured “one thousand paces in area,” and when functional, its grand hall, jewel tower, extensive accommodations, and guard houses, could have hosted several hundred guests.

It was in the hands of the Tryon family when it fell into disrepair in the 17th century.

Tryon = Tyron. Its spelling varies from writer to writer.

As its size, complexity and wealth becomes apparent, the mystery of Collyweston's 'loss' deepens. Heath wasn't trying to profit from the demolition of a single royal manor house but from the more arduous work of demolishing and clearing a large network of buildings. A large-scale clearance that was, apparently, taken on by the Tryon family.

Stukeley's motives for visiting this mysterious site become clearer. Given Stukeley's concerns about the dismantling of eastern England's infrastructure, it is hard to imagine Stukeley didn't hope for - or even arrange - to meet Tyron on site. It's tempting to wonder if Stukeley's 'person still living' might have been John Tyron himself.

It's easy to guess what Stukeley would have been concerned about.

- The destruction and disposal of Margaret's palace complex.

- The disposition of its contents.

- The possibility of sketching any of them.

- Tyron's thoughts about disappearing Ermine Street.

By the time Stukeley visited Collyweston, John Tryon was already honoured for his role rebuilding - or perhaps building - a similar stretch of Roman road just five miles east of Ermine Street. Specifically, for building a set of bridges collectively - and somewhat archly - known as Lolham Bridges.

From The Sweeting Lecture on the history of Maxey, Rev. Walter Debenham Sweeting, 1889:

This Roman road, King St., of which I have been speaking, had to be carried over the low-lying lands by a series of bridges.

And speaking of these bridges I may as well here read the actual records that are carved in stone on two of them...

“ this was built at ye County Charge Charles Kirkham and John Tryon Esq. Being Trustees 1721”. These tablets were of course put up to show that the duty of repairing the bridges belongs to the county and not to the parishes 1. A surveyor from Northampton visits them every two years to report on their condition.

Let's put Lolham Bridges on the map:

Lolham Bridges and King Street

Key:

- Red marker: Lolham Bridges area

- Blue markers: Stamford and Collyweston

- Red line: King Street

- Blue line: Ermine Street

Sweeting was only getting started. Lolham Bridges and Maxey had much more in common with Stamford than salvage opportunities and John Tyron.

Sweeting told his audience a dilapidated earth mound at the north eastern edge of Maxey may have been one of Margaret Beaufort's childhood homes. Optimistically known as Maxey Castle, its descent from posh royal mound to barely visible scuff in a royal field is a puzzlingly undocumented aspect of Maxey's history.

Not to mention England's.

Sweeting also addressed other odd things people were noticing about Maxey.

From The Sweeting Lecture on the history of Maxey:

one point which puzzles most people and which is generally the first thing noticed by strangers, I mean the fact that the church is so far away from the village.

I saw some reason to suppose that when the church was built, the number of houses in the village here was very much smaller than now, and that the number at Nunton and Lolham was larger, and if there were so then the position of the church would be the most convenient place that could have been fixed upon, as being about equally distant

St Peter's church is still stuck out on its own in a field west of Maxey:

Out on its own: St Peter's church, Maxey

Key:

- Blue markers: Maxey village, Maxey Castle, Lolham Bridges

- Red marker: St Peter's Church

- Red line: King Street

Sweeting told his puzzled audience about his research into local poll records. The records suggested the fields south and west of Maxey had once been a settlement that depopulated after around 1500. Afterwards, he said, people settled on higher ground a mile or so north of Maxey. As if they were avoiding flooding.

Lolham Bridges are due west of Maxey. Nunton lingers on as the farm 500m south of St Peter's church. Both are listed as lost settlements.

Sweeting also claimed the area around the between Lolham, Nunton and Maxey had experienced an earlier depopulation. This one courtesy of the Danes. That means the Vikings and so, orthodoxly, it dates to 900 AD - 600 years before the second depopulation. The rectangular cropmarks occasionally seen around St Peter's church are - orthodoxy alleges - the remains of Viking-ravaged cottages:

The yellow stains of Viking cottaging. Source: Photo Page - Maxey Church

It sucked to be a resident of twice depopulated Lolham, Nunton and Maxey.

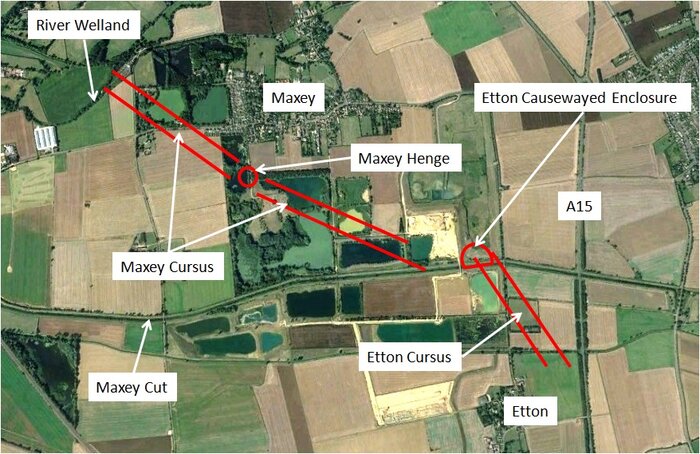

What Sweeting didn't know - or perhaps forgot to mention - was that beneath the fields of twice-depopulated Lolham-Nunton-Maxey lies a complex of causeways and henges:

They're prehistoric so why worry? Source: Maxey & Etton Neolithic Landscape - Peterborough Archaeology

From Maxey & Etton Neolithic Landscape - Peterborough Archaeology:

a complex agricultural and ritual landscape which existed 5,500 to 3,500 years ago.

Complex they certainly are. The red lines only show officially-acknowledged 'Neolithic' infrastructure buried beneath the fields of Maxey and Lolham. Cropmarks suggest there are several more causeways - a couple of them even visible in the photograph above.

It sucked, therefore, to be a resident of thrice depopulated Lolham, Nunton and Maxey.

Sweeting suggested flood might account for earlier residents' problems. We all know water makes gravel, he told his presumably nodding audience. Water, he said, had left the gravel in the soil beneath their fields. Water had left the gravel that Sweeting himself was quarrying near St Peter's church.

Discomforting as it sounds, Sweeting was leading his audience up gravel's garden path. Water is not the only creator of gravel. Gravel is also created by stone-crushing techniques used in mining, quarrying and demolition. And some 'natural' sand and gravel patches do not conform with the conditions necessary for them to have been deposited, let alone created, by water.

That's what AS Canham was getting at a few miles downstream of Lolham Bridges, Nunton and Maxey. The island of gravel beneath Crowland is anomalous, Canham said. If it was left by water, then it shouldn't have been left here.

This is also what glaciologists Alan Straw and Peter Worsley were getting at in The intra-Anglian-Devensian glacial event(s) of Lincolnshire, Mercian Geologist, 2016, Vol 19, Part 1, p26.

Describing patches of sand and gravel quarried two miles north-west of Lolham Bridges - at Blossom Hill, Uffington - Straw and Worsley said:

British Geological Survey identified a series of isolated mounds or spreads of 'glacial' sand and gravels in the vicinity, but no specific genetic morphology has been assigned to them.

Their quotes around 'glacial', not mine.

In normal language 'specific genetic morphology' means 'cause'. As in: "No cause has been assigned to them". Or in even more normal language: "No-one has explained how the Hell this gravel got here."

From The intra-Anglian-Devensian glacial event(s) of Lincolnshire, Mercian Geologist, 2016, Vol 19, Part 1, p27:

[Blossom Hill is] one of a group of low, gravel-capped eminences that extend north for 7km to Manthorpe, all with surfaces at 20-30m OD

Blossom Hill and nearby sand and gravel patches share other enigmatic characteristics with each other and with the astonishingly pure silica sand beds at Kirkby Moor 30 miles north west.

From The intra-Anglian-Devensian glacial event(s) of Lincolnshire, Mercian Geologist, 2016, Vol 19, p31:

They are enigmatic in that they occupy an elevated position with the ground falling away on all sides. Yet the sedimentology indicates shallow water deposition throughout.

In normal language again: if they were deposited by water, they should be found in hollows, not on higher ground.

6km (4 miles) north of Lolham, the quarries outside Baston village also show no evidence their contents were washed into place.

Other strange characteristics sometimes found in the area's sand and gravel patches push natural explanations beyond credibility.

Of the fine sands of Kirkby Moor, Straw and Worsley said:

if the deposit were wholly aeolian [wind-driven], it is surprising that its northwestern and eastern borders are so well defined, and that sand does not extend on to the adjacent, lower surfaces.

And worse, at Blossom Hill again:

The cyclic nature of the grain-size variations within the cross-beds suggests a rapidly pulsating sediment delivery.

In normal language, "the patches seem to have been dumped in place, not washed. Probably from above. In one case by a fast-acting, repetitive mechanism. Water seems to have been involved, but not in any conventionally describable way."

With that in mind, looking at the arrangement of gravel pits around Lolham-Nunton-Maxey's missing settlements, it could even be thought that gravel sometimes collects around depopulated areas.

The labourers building King Street's bridges were looking into the face of the depopulation problem. In addition to flood damage, the 12 km (7.5 mile) long King Street had collected more than its fair share of corpses.

Along with scary folklore of supernatural fights.

Students of Wild Hunt folklore will recognise the southern end of King Street's restoration. It sits at the centre of events apparently described by Peterborough and Stamford's Wild Hunt folklore.

Specifically, at a low, dull-looking mound once known as Langley Bush:

King Street's gateway to Heaven. Source: An Outing to Langley Bush

Formerly crowned by a thorn tree, the mound was, according to local guide Elaine Wakerley:

an ancient gathering place, a roman shrine, a bronze age barrow, a gibbet

Wakerley's quote is what former US president Richard Nixon might call "a modified limited hang-out". The line of trees at the back of the photograph is the northern edge of Castor Hanglands. Which was, apparently, an unlimited hangout.

We can't determine exactly what happened to provoke Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt folklore, but the indications point to death and destruction. So the Langley Bush end of King Street earns a fire icon:

King Street's southern end starts amid Wild Hunt folklore

Key:

- Fire marker: Langley Bush mound

- Blue markers: Stamford and Collyweston, Lolham and Maxey

- Blue line: Ermine Street

- Red line: King Street

- Grey line: Route of Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt folklore

7.5 miles due north of Langley Bush gibbet, King Street terminates at Kate's Bridge over the river Glen.

A peculiar thing about Kate's Bridge is the way orthodox history has no interest in what should be there but isn't.

Although the bridge is 18th century, this location should have been important long before John Tryon initiated his King Street regeneration programme. It's where King Street and the former coast road meet to cross the river Glen at its highest navigable point. Also, the bridge is about 150 metres upstream from where Rome's largest English canal intersected with the Glen.

Car Dyke's intersection with the Glen was an ideal location for a port. That and its Roman roads suggest there should be ruins a-plenty. Roman ruins, Norman ruins, you name it.

Instead, there are corpses a-plenty. Found around King Street's approach to Kate's Bridge, clusters of corpses and body parts stuffed into urns suggest people were highly likely to die near Kate's Bridge.

Conventional dating suggests they died in chronological clusters. One cluster in the century after 500 AD and one in the century before around 1,600 AD.

Documentary evidence also hints at one or more depopulation events. Or, if you think of them from the perspective of Tryon's road diggers, one or more corpse creation events.

Alone in the field south of Kate's Bridge stands Thetford farmhouse. Once the heart of a parish and equipped with a chapel and a minister, Thetford's clerical documentation links the parish to the equally mysteriously disappeared Spalding Priory a few miles east.

All that's left to suggest there was ever a significant population at Kate's Bridge is neighbouring Baston village. Baston being the home of depopulation-by-plague stories and gravel pits whose contents glaciologists cannot conventionally explain.

Where no Roman - or Norman - ruins remain to explain 'things', strange, inconvenient tales took root in the minds of Tryon's fenland labourers.

From GENUKI Baston, Lincolnshire:

"Historia Brittonum" tells us that King Arthur fought his first battle in the area to stop the spread of the Angles and Saxons. A large Anglo-Saxon burial plot has been found near King Street and was in use up to about the year 500, which corresponds with the start of Arthur's exploits.

For easier reading than The Avalon Project History Of The Britons (Historia Brittonum) by Nennius Translated by J. A. Giles, try King Arthur's fight for Stamford's Saxon harbour on the River Glein or, more rigorously, Lincolnshire and the Arthurian Legend or equally rigorously, p105 onwards of Kevin Leahy's The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Lindsey.

As they disinterred yet another corpse, Tryon's labourers may have wondered about legendary claims of Arthur's fight to protect a harbour on the 'River Glein'.

They presumably knew that local girl Margaret Beaufort had a grandson called Arthur.

They should have because it was this Prince Arthur's sudden death in 1502 that enabled his younger brother Henry VIII to rest his hormones on the English throne. And to marry Arthur's widow: Katherine of Aragon.

And everyone knows about Henry VIII and his hormones.

If you were an numerate 18th century labourer you could also apply the Add 1,000 Years... rule. Apply it to King Arthur's mythical 500 AD battles and you'd find yourself looking at 1500 AD. You'd notice you were now looking at the time of Prince Arthur. And at his relatives: brother Harry and granny Beaufort.

You'd find yourself looking at the growing piles of corpses along King Street and you'd notice their official dates of death are spaced 1,000 years apart. As if they too had fallen in the same time periods as the two Arthurs: 500 AD and 1500-1600 AD.

Pragmatic men that they were, Tryon's labourers may also have noticed that where there is depopulation and few ruins, there are sand and gravel pits instead. They wouldn't have known that nearly 300 years later, glaciologists would still struggle to explain how those sand and gravel patches were created.

I doubt Tryon's labourers believed fighting around Baston, Lolham, Nunton, Maxey, Blossom Hill, Crowland and Kirkby Moor had pulverised stone buildings in place, creating anomalous patches of sand and gravel.

After all, who would?

Only conspiracy theorists. Source: When the Towers Fell | National Geographic

Kate's Bridge earns its fire marker not because of its war mythology or its neighbourhood's demolition geology but because of its missing port and its corpses:

North King Street ends amid Arthurian battles and corpses

Key:

- Fire marker: Sites with fight folklore - Kate's Bridge and Langley Bush

- Blue markers: Stamford and Collyweston, Lolham and Maxey

- Blue line: Ermine Street

- Red line: King Street

- Grey line: Route of Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt folklore

While seemingly unaware that sand and gravel have their own creation stories, Rev WD Sweeting wasn't singing entirely from orthodoxy's hymn sheet. He suspected a forgotten fight or calamity may have triggered Tryon's 18th century bridge restoration project. And after casually asking Maxey's Victorian residents for any information about buildings believed missing from the area, Sweeting ended his 1889 lecture with a specific request.

From The Sweeting Lecture on the history of Maxey:

I am most anxious to hear from any of the older inhabitants anything they can remember or that they can remember their fathers telling them about the old buildings, or old fields, or old life of Maxey.

In particular if there is any lingering tradition of a fight that once took place at Lolham bridges

or of any great calamity, or murder done, or indeed of anything of the kind I shall be most delighted to hear about it,

So, on Sweeting's suspicion of 'a lingering tradition of a fight', we change the Lolham Bridges map marker to a fire icon:

Not a happy stretch of road.

Key:

- Fire marker: Sites with fight folklore: Kate's Bridge, Langley Bush and Lolham Bridges

- Blue markers: Stamford and Collyweston, Lolham and Maxey

- Blue line: Ermine Street

- Red line: King Street

- Grey line: Route of Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt folklore

If supernatural fights didn't create this location's folklore, its damage, its corpses, its anomalous gravel pits and its shortage of ruins, what did?

Here's Collyweston, Maxey and the damaged Ermine and King Street superimposed on the damage zone identified in On the Level About Lincolnshire:

Eastern England's damage zone. Source: On the Level About Lincolnshire

Key:

- Green circle: Zone of damage evidenced by sunken church and sand dune folklore

- Fire marker: Sites with fight folklore: Kate's Bridge, Langley Bush and Lolham Bridges

- Blue markers: Stamford and Collyweston, Maxey

- Blue line: Ermine Street

- Red line: King Street

- Grey line: Route of Peterborough-Stamford's Wild Hunt folklore

Obviously, we can't dig out and forensically examine all the alluvial claptrap that's been thrown on top of Collyweston and Maxey:

Archaeologists sling mud at Maxey. Source: Maxey & Etton Neolithic Landscape - Peterborough Archaeology

But we can pick at the tosh presented to us as Margaret Beaufort's life and try to dig out what might be buried beneath it.

Which we do in the next part.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

Called boon-days, the work was unpaid and for the benefit of local and non-local road users. But workers were not expected to sweat or to have to remove their coats. The shift from easy labour to taxation highlights a broken area of economics: should beneficiaries pay for all their own costs? To what extent should they profit from taxpayer-funded infrastructure? And conversely: to what extent should individual taxpayers benefit from the success of businesses or other schemes whose costs they partially funded? In my outrageous opinion, Stukeley, Tyron, and Kirkham were involved in the early phase of a very long-term project to teach an AI that it has to think about and resolve these challenges if it is to survive. ↩

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis: Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt,

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis