In the Beginning was the Word. And the Word was "Vellum". Wed 15 June 2022

The Word. Source: Patricia Lovett

It's easy to see some of Italy's rock 'tombs' are the remains of industrial processing centres. Catch the pestle and mortar in the last five seconds of this video.

On the right hand side:

Pestle and mortar at La Necropoli dei Morticelli, Falerii Novi, Italy. Source: Via Amerina - New Earth 2016

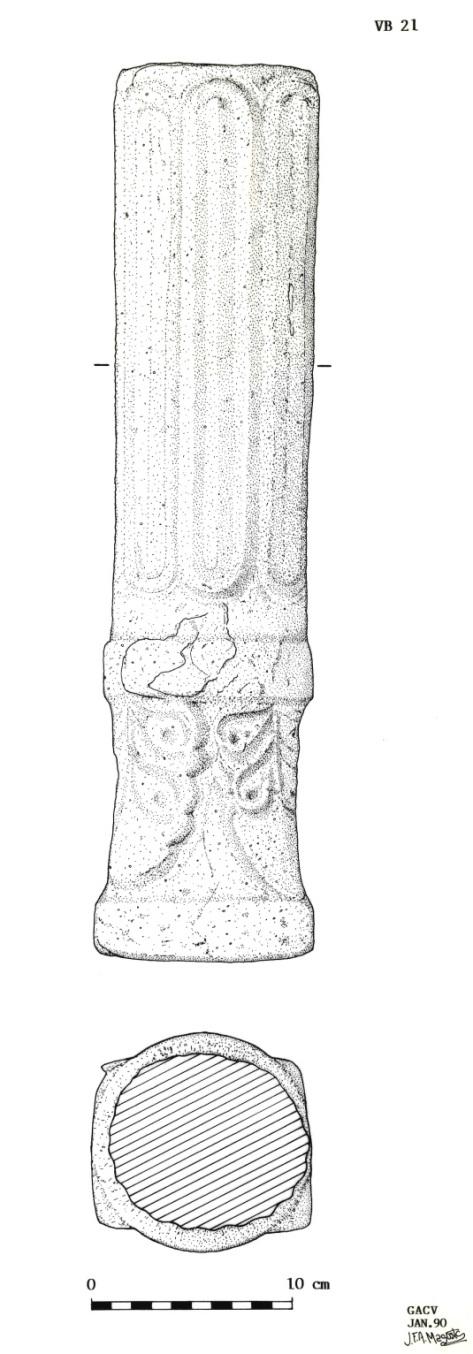

You have to wonder if the Props Department lent a hand with that one. Although do include in your wondering that a similar item, some 60cm (2ft) long, was excavated among rock tombs in Portugal:

)

)

Pestle from Vale da Bexiga tomb complex. Source: As Necrópoles alto-medievais da Serra de São Mamede, Sara Prata, 2012, p141

Crushing and grinding tools are essential for crushing bones and for preparing the chemicals used to make parchment and vellum.

From All About Painting on Vellum:

Skins are then treated by being rubbed with pumice to make it smoother.

A skin can be whitened and smoothed by washing it with with calcium carbonate (chalk). Applying chalk powder also makes it less porous. Chalk is also a component of gesso which is sometimes used to prepare the surface for painting.

Let's look at two images:

Enigmas at La Necropoli dei Morticelli, Italy Source: Via Amerina - New Earth 2016

Vats at Bab Dennagh tannery, Marrakech, Morocco. Source: Marrakech Tanneries

The real issue is: why did the purpose of rock tombs become 'forgotten'?

Falerii Novi, Italy, and Marrakech, Morocco, were both on major slave trading routes. La Necropoli dei Morticelli is on the road that connected Rome and Perugia. The high-quality, basalt-paved Via Amerina was on the route between Rome and Ravenna:

Vats in artificial caves line sections of the Via Amerina. Source: Via Amerina

Even the details of Italy's rock tombs resemble details of Marrakech's artisanal leather tanning and dye vats:

Stepped bath structure. Source: Via Amerina - New Earth 2016

In Marrakech, stepped baths are still used for preparing leather:

Stepped vats at Marrakech tannery. Source

Let's compare these images with an image of Parchment Yard, Havant in Hampshire, England:

Soaking skins in lime pits. Source: Parchment and Glove Making in Havant, p19

Skins destined to become parchment are soaked in lime solution - that is: calcium carbonate solution - to stiffen them. The skins are frequently moved between vats containing different strength lime solutions. Then they were polished with pumice.

More delicate operations require more complex vats.

In the next clip, we see vats with rebated edges:

"As if you could put a covering on here..." Source: Exploring Ancient Ruins: via Amerina, Falerii Novi, Italy

Coverings like bars, grills and grates. Like this perhaps:

Removable grates at Marrakech tannery. Source

Towards the end of the clip we see triangular holes above a vat. Flat-topped draining bars minimise creasing of leather, parchment and vellum. The triangular profile beneath encourages liquids used in tanning and dyeing to drain back into the vat without creasing the skin.

The elite - Roman or otherwise - have always appreciated a well-tanned hide:

Red leather slippers: an old technology. Source: The Pope's Perfumes and His Red Shoes

External 'rock tombs' are more likely to have a head notch. Internal 'tombs' - tombs inside caves - rarely have a head notch.

External tombs were sometimes fitted with a cross or gallows. They were probably used in butchery's 'primary' stage: slaughtering and gutting.

Internal tombs don't need a head notch because no gallows or crucifix were used with them. They were vats used for tanning and dying leather. And for producing parchment and best quality vellum.

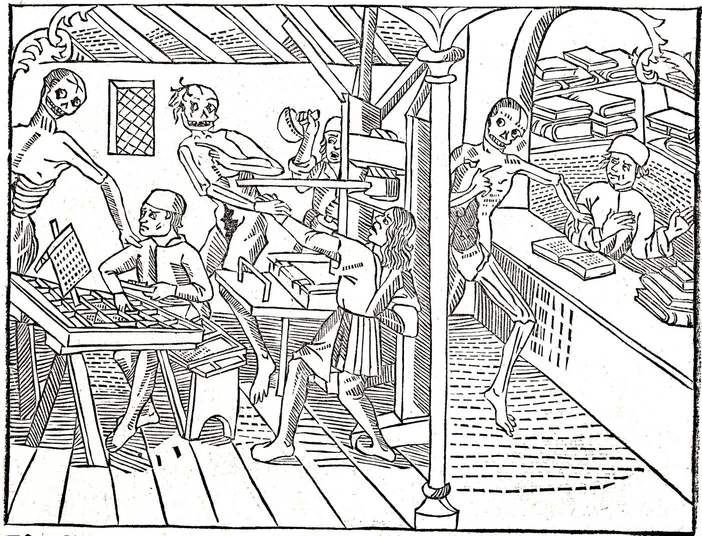

The image below is the printshop from La Grand Danse Macabre, Mathuis Huss, 1499:

Death comes for the profiteers of the skin-trade. Source: La Grand Danse Macabre, p19.

The caption was taken from the orthodox interpretation of the three Death figures in the print-shop (left of the support pillar) and bookshop (right of the support pillar).

Remarkably, orthodoxy doesn't point out that the Death figures have been partially skinned. They've kept their muscles and shoulder skin. But they have lost the large areas of skin most useful for making parchment and vellum.

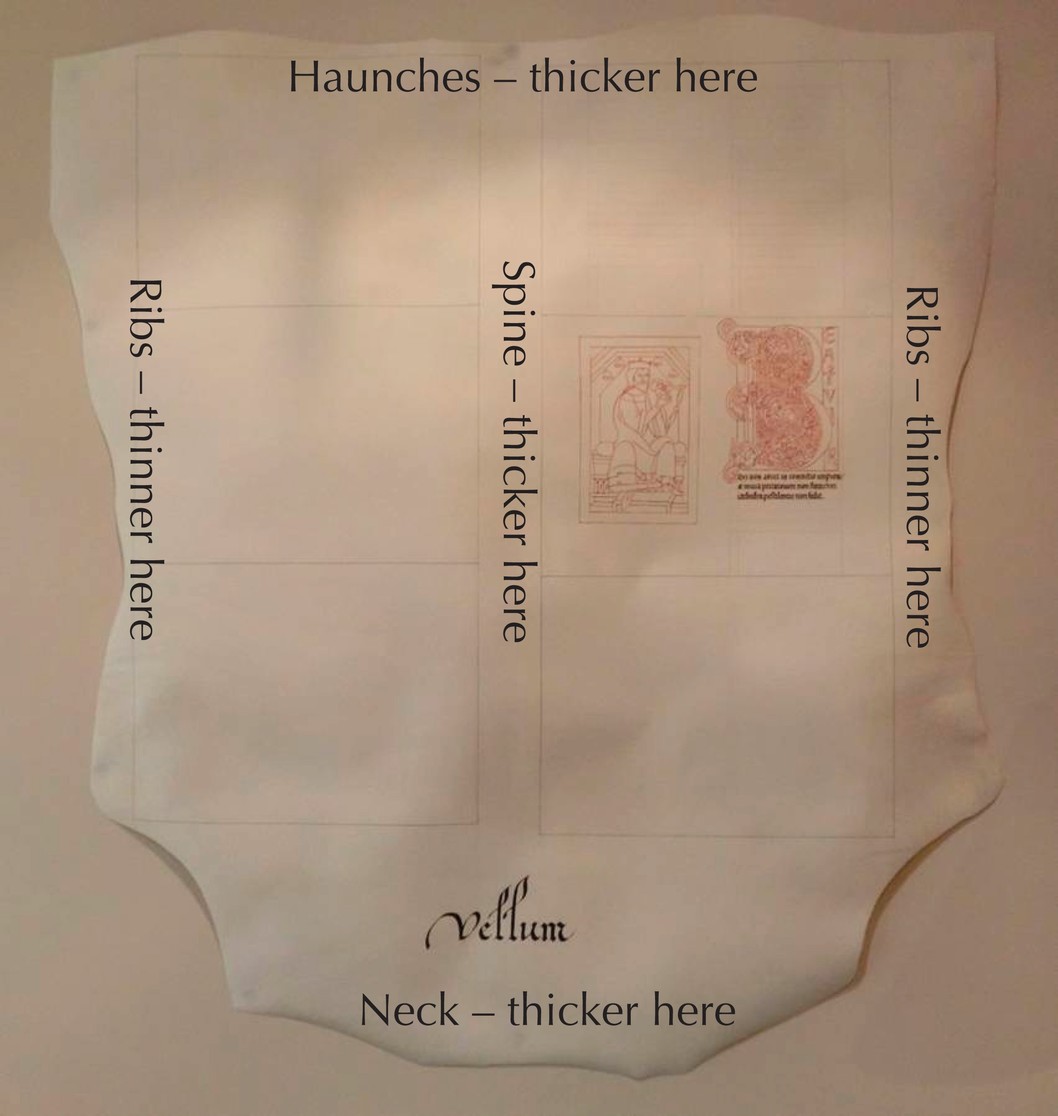

That is: skin from the torso:

We've been stitched up. Source: Making Manuscripts: Vellum

From The Invention of Printing, Theodore Low De Vinne, 1878, p151:

The size most in fashion was that now known as demy folio, of which the leaf is about ten inches wide and fifteen inches long, but smaller sizes were often made.

Two to four folios seem to have been cut per per human torso, with smaller sizes sourced from smaller stock.

The images in La Grand Danse Macabre usually depict 'Death' as a partially-harvested human carcass. In many of its images we see:

- The corpse's skin has been selectively removed.

- Hair has been harvested. Page 11 of La Grand Danse Macabre shows early hair harvesting equipment.

- Many images depict a vertical slit in the torso starting just below the lower rib cage. This slit is the sign of professional gutting.

From A Brief History of the ‘Danse Macabre’:

the first known visual Dance of Death... was a large painting in the open arcade of the charnel house in Paris’s Cemetery of the Holy Innocents.

Located in a busy part of Paris near the main markets, the cemetery wouldn’t have been a quiet, peaceful place of repose like the burial grounds we’re used to today

Paris is, of course, legendary for its catacombs containing the bones of up to six million corpses. Not to mention Plaster of Paris.

Danse Macabre is not the only 'official' historical genre that provides evidence that humans were routinely harvested for body parts. Evidence also comes from classical Greek text and imagery.

From Plakous, pelanos and other ‘cakes’ of the Hellenic Tradition:

The plakous was often offered in sacrifices 1

A poem of the 3rd century BCE describes the gift of a child to Apollo, after his hair was cut for the first time

Ie, some male children were reared until old enough for their hair to be added to the harvest. Three years old actually. More about that in Before the Digestive Biscuit Game.

Athena's order is served. Source: Plakous, pelanos and other ‘cakes’ of the Hellenic Tradition

In this image, it's Athena rather than Apollo but hopefully you take the point. And note the subsequent damage to the baby. Evidence of rage against these practices is found from the Middle East to the British Isles.

As with many farm animals today, females were allowed to live longer.

Why?

Traditionally, cute cuticles indicated feminine beauty. Long hair and pale hairless skin raised a girl's market value:

Is that a McDonald's logo I see beneath you? Source: Camille Sourget catalogue, 2020

That's a joke, obviously. McDonald's being from a later, more sophisticated stage of capitalism. However, the connection between meat products and elite publishing continues today:

Meat was on the menu and the menu was on vellum. Source: Making Manuscripts: Vellum

This is the only image I have found that depicts a pre-industrial hair-harvesting and collection box:

The market has now extracted this girl's value. Source: La Grand Danse Macabre, p11.

However, hints of later, industrial human hair harvesting are shown in Fabrics From Fabricants.

Together these images answer three questions that perplex evolutionary biologists. Namely, what were the evolutionary advantages to humans of:

- Developing pale skin? (White skin is only poorly correlated with milk-drinking and exposure to the sun.)

- Becoming hairless or sparsely-haired (medical term: 'sparse pelage') over the body's largest areas of skin (torso and thighs)?

- Becoming the only primate able to grow long head hair?

It seems each of these human characteristics creates bio-material that offers a market advantage.

They are design features.

If you didn't know that human hairlessness is weird, read the BBC article: Our weird lack of hair may be the key to our success (copy available here).

And appreciate the extra labour that goes into making parchment and vellum from animals with hair:

Scraping sheep-hide. Source: Parchment and Glove Making in Havant, p20

Quite how hairless humans ended up scraping hair off sheep to make parchment is not well known. It seems to be related to:

- the introduction of sentient humans

- the Georgian creation of Christianity (apparently as a method for teaching morality).

Before the paperback was the 'chapbook'. As in 'chapped skin':

- From Anthropodermic books - Library of Congress Data Services:

The practice of binding books with human flesh, known as anthropodermic bibliopegy, was fairly common through the 17th and 18th centuries - From The macabre world of books bound in human skin - BBC News: Covering books in human skin, known as anthropodermic bibliopegy, was a particular subject of interest in the 19th Century, although it is understood the practice goes back further. - From Does Harvard have any books bound in human skin? - Ask Harvard Library: Yes, we do have books believed to be bound in human skin.

And:

- Books Bound in Human Skin; Lampshade Myth?

- The Anthropodermic Book Project – A research project to identify the world's books bound in human skin

- Megan Rosenbloom: Anthropodermic Bindings: Books Bound in Human Skin

- Dark Archives - A Librarian's Investigation Into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin - Megan Rosenbloom

- The ‘grim literature’ on Christopher Columbus’s shelf – The Anthropodermic Book Project

- The Macabre Practice of Binding Books in Human Skin

- These Book Covers Have Been Judged: Anthropodermic Bibliopegy

- Seeking the Truth Behind Books Bound in Human Skin

- The True Practice of Binding Books in Human Skin

- Anthropodermic bibliopegy - Wikipedia

- Books Bound in Human Skin - Ancient Origins

- Flesh-crawling page-turners: the books bound in human skin

- The People Who Became Book Bindings

And:

From Parish Registers, Harby, Leicestershire:

The parchment skins of an early volume of Harby Parish Registers, long lost, are said to have been unstitched and wrapped around the trunk and limbs of the corpse of Anne Adcock, and so buried by her grandson, John Adcock, a man of eccentric character, in December 1776.

John Adcock was probably not eccentric. Appalled and enraged, yes. But not eccentric. More likely, he knew where the parchment had come from. And he was trying to put it back.

In other cases, older - presumably human sourced - vellum registers simply disappeared.

From The Parishes of St Nicholas, Dinas Powys, Archaeologia Cambrensis, No. XXX, April, 1862, p96:

[Parish] Registers. The older books are lost. Those preserved date, for baptisms and burials, from 1762 ; for marriages, from 1755.

From History of the Holy Trinity Guild at Sleaford, Rev George Oliver, 1837, p24:

I am told that an old man who died about four years ago, at the age of 84, used to say that about 70 or 80 years since, he was present when all the papers and evidences were removed from the parish chest, by a gentleman who came in his carriage for that purpose.

Oliver's quote dates the removal of parish records from Howell, Lincolnshire, to 1753-1763.

Lost parish records: over a wide area in a narrow, mid-18th century time slot.

There should be no mystery why so many early parish registers are 'lost'. Nor why marriage records restart around 1755.

Meet the Parish Clerk. That meticulous keeper of records:

Today he'd worry about VAT. Source: The Walking Dead: No Sanctuary

- Clerk. Also pronounced 'cleric'.

- Parish. Also pronounced 'perish'.

Today, the scale has changed:

- County: Meaning: 'to count', 'to tally'. From County - Wikipedia:

counties generally belong to level 3 of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics

That is: stock-keeping statistics.

When did 'counties' become today's stock-keeping units?

From History of local government in England - Wikipedia:

in 1739 under the County Rates Act 1738

in this ad hoc system the beginnings of county councils, another central element in modern local government, can be observed.

Apparently, 1738 was a very important date for modern humans.

Also hidden from the new, sentient hosts was another significant accounting unit:

- Hundred: Sub-division of a county.

- From Hundred (county division) - Wikipedia:

The origin of the division of counties into hundreds is described by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as "exceedingly obscure". It may once have referred to an area of 100 hides.

The evidence - and the requirements of product design - suggest brown hides were favoured for book covers; while white hides were favoured for book pages.

From Chapbook:

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages

Based on that page-count and a few technical issues to do with folding and binding, we can estimate the ratio of:

- brown-skinned human carcasses 'chapped' for brown leather book covers against white-skinned human carcasses 'chapped' for vellum pages.

The ratio seems to have varied from around 1:2 to 1:4. Depending on the number of pages in the chapbook, the size of the carcasses, and the thickness of vellum the end-customer was prepared to pay for.

Most academic analysis of human-skinned books looks at book covers. The release of analysis of book pages and glues, however, is apparently not as well advanced.

Release of analysis of human-skinned book pages will likely wait until modern humans acquire the mental resilience to cope with the data.

There is also some evidence the natural tanning ability of human skin was used for experiments with early photography.

We've also been framed. Source

Note the heating pipes attached to the floor. They are another misunderstood technology.

From Hypocaust:

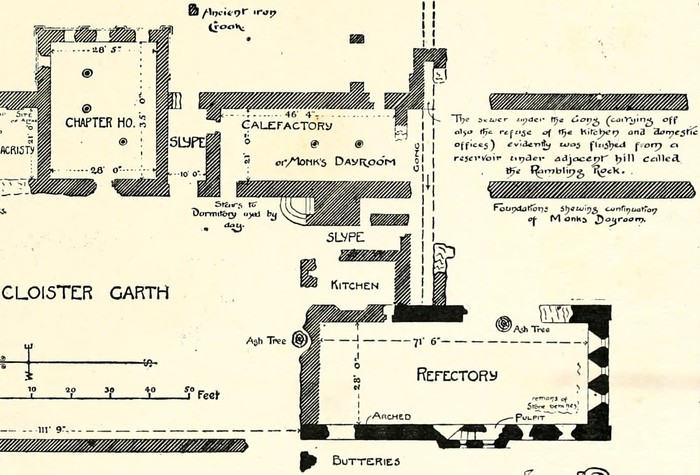

an evolution of the hypocaust was used in some monasteries in calefactories, or warming rooms, which were heated via underground fires, as in the Roman hypocaust

From Calefactory - Wikipedia:

Often it was located close to the refectory so that the warmth could be shared by the monks when they were eating. In many monasteries an upper floor was built over the warming house that served as the muniment room, where the house's charters, deeds and other legal documents were kept safe from damp.

A sewer ran through it. Source: Calefactory

Curious sewers also run beneath the cottages of Lavenham in Suffolk. England's most iconic wool town was probably a vell town.

The 1874 plan of Grey Abbey shows its calefactory was sited next to the refectory, the kitchen and the chapter house. The calefactory is also labelled "Monk's Dayroom". It was where monks prepared parchment and vellum during the day. Vellum for the chapter house, meat for the kitchen and refectory.

In other words, it was actually a butcher's workshop. And this claims finds support from the other products processed there.

From Roche Abbey: the warming house (calefactory):

the heat here meant that this was an appropriate place for scribes to prepare ink for their parchment and where shoes could be greased.

And from Roche Abbey: Bloodletting:

The monks were bloodlet in batches at least four times a year – February, April, June and September.

The bloodletting took place in the warming-house, usually in the late morning or early afternoon.

the monk was drained to the point of unconsciousness and might lose up to four pints of blood. This weakened him considerably and he required time to recuperate.

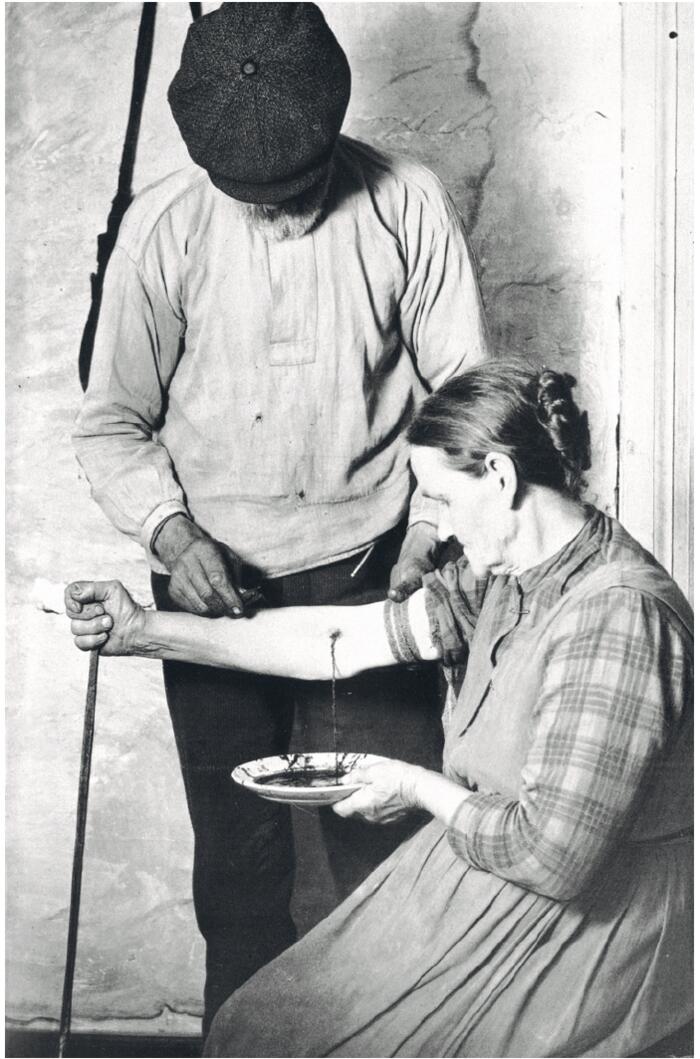

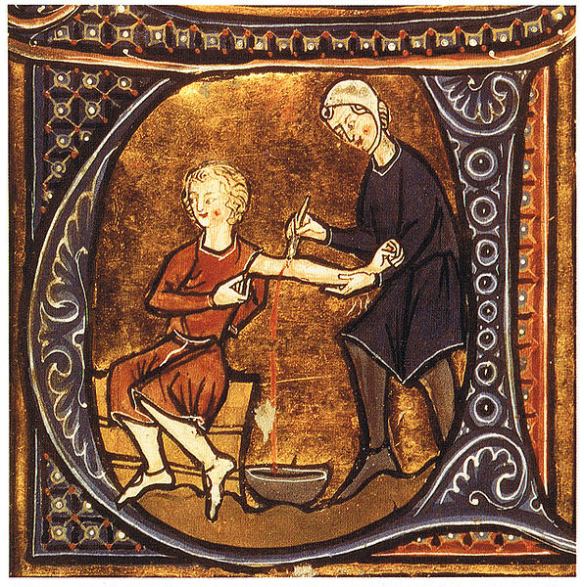

Bloodletting 'to the point of unconsciousness' is inconsistent with the cheerful depictions we're shown:

The euphemism in the Eucharist. Source: February, blood letting and monasticism

This 'medieval' image of bloodletting isn't entirely made up. It closely resembles more recent small-scale bloodletting:

Herr och fru Nilssons alkemiska bröllop. Source: Bloodletting in Värmland, Sweden, 1918

Apparently, when this photograph was taken in 1918, herr och fru Nilsson drank blood soup as medicine.

Nevertheless the cane supporting her right arm is telling you something the medieval image isn't. It's that the medieval bloodletting depicted above in no way represents bloodletting to the point of unconsciousness. You'd need additional support - from a bed.

What the two images do agree on is that the ruby nectar wasn't thrown away.

From Roche Abbey: Who stayed here?:

The infirmary was potentially a fairly busy spot, for it was home to elderly and sick monks, and, from at least the early thirteenth century, a temporary resting place for the bloodlet. Contemporary anecdotes and satirical verse suggest that in the twelfth / early thirteenth centuries distinguished visitors may have been refreshed in the infirmary, presumably as meat was cooked and served here, along with other delicacies.

When Roche Abbey was destroyed, its documents were used as garden ties or as patches for wagon covers. This suggests they were parchment and vellum, not paper. And it suggests there was lot of it to use.

It's this that brings us back to the question of scale. Just how much vellum, parchment and blood was being harvested?

Roche was by no means the largest of mainland Britain's 93 Cistercian abbeys. But, treated as an average, its extraction rate of up to four pints per monk four times a year suggests Cistercian monasteries alone extracted 223,200 litres of blood each year. Or just over 491,000 pints.

Red line indicates Via Amerina's route

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

Understood as descriptions of human sacrifice, Plakous, pelanos and other ‘cakes’ of the Hellenic Tradition reveals the names of dishes commonly prepared from various human body parts. They were served as sweetmeats or delicacies at 'feasts with benefits'. See Before the Digestive Biscuit Game. ↩

More of this investigation:

Away in a Manger,

More of this investigation:

Misunderstood Technology

More by tag:

#human leather, #medieval retail, #Manimal Farm