A map of pre-Victorian Grimsby helps us understand why mystery and mimic plays were suppressed. Sat 05 February 2022

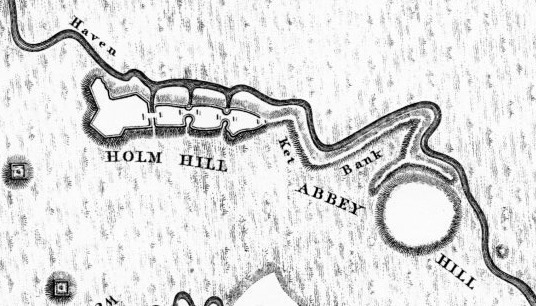

Holm Hill, Ket Bank, Abbey Hill. Grimsby, UK. Source: The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby, Rev George Oliver, 1825

The above image is from Rev George Oliver's 1825 book The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby. It was clipped from Rev W Smith's plan of Grimsby - the only known depiction of Grimsby's Ket Bank serpent mound complex:

Smith's pre-1825 plan of Grimsby serpent mound. Source: The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby

It's drawn as if approaching Grimsby from the north-east. From the sea.

Re-oriented with north at the top, it looks like this:

One old Grimsby mystery is the nature and purpose of the curved line of small, square islands Smith labelled "Block Hills". More visible in the first image.

Perhaps the "Block Hills" looked like this:

Apparently blast damaged artefact in Gulf of Finland. Source: The Lost Legacy

So "Block Hills" may have been mooring posts. They may have been gun emplacements whose cannon were re-mounted as mooring posts. Or they may have been something else.

Whatever they were, there seems to be no trace of them in Grimsby today.

For an idea of how that intersection between Ket Bank and Abbey Hill looked, see the Construction Techniques section of Twists in the Tale of the Serpent Mound. The construction technique shown in Durham University's image of a motte and bailey mound on that page resembles Rev George Oliver's description of Grimsby's Ket Bank complex. Though Grimsby's mounds may have used more stone than timber.

Where was the Ket Bank and Holm Hill complex? Sprawled over the south eastern side of Grimsby. East of today's Bargate:

Ket Bank serpent mound superimposed on Grimsby's modern street plan.

The southern end of Ket Bank's Holm Hill are still called Holme Hill. The remains of Ket Bank's extreme north eastern end are visible as raised ground beneath St Mary's Church:

Elevated ground level beneath St Mary's church. Source: Google Maps

The next map attempts to identify the locations of all the hills Smith plotted:

Ket Bank serpent mound complex, Grimsby, Lincolnshire

Key:

- Red marker: Named hill or mound

- Grey marker: Unnamed hill or mound

There are few obvious clues about who built Grimsby's serpent mound complex. Nor when, nor why.

We're given one clue about why it was destroyed.

From the early 19th century onwards, Grimsby's mounds were dismantled. Their materials - mostly sand and stone - were used for building. But there is also evidence of a destructive aerial event over Grimsby in the 16th or 17th century.

'Ket Bank' brings to mind the so-called cattle 'rest places' called 'Coldharbours'. Just like serpent mounds, 'Coldharbours' are always near rivers and estuaries. They are usually sited near a village or hamlet called 'Little London' 1. There is a hamlet called Little London on Stallingthorpe Road halfway between Grimsby and neighbouring Immingham.

'Little Londons' tend to be associated with pottery making. Which means kilns and access to the consumables of pottery making:

- clay

- wood

- bone, and wind or watermills to grind bone.

If bone-milling seems a speculative stretch, bear in mind Rev George Oliver wrote that the high Lincolnshire Wolds were 'marled' to make them fertile. 'Marl' being ground bone: bone-meal.

Rod Collins' Grimsby hills research linked the 'Ellyl Hills' on Smith's plan to the Welsh word for demon or fiend: 'ellyl'.

Oliver gave us a similar clue when he described Grimsby's three 'Ellyl Hills' and their residents.

From The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby, p58:

The principal hill... is called El hill, Hell-hill, or Ellyll.

And on p59:

... the appellation of Hell-Hill, as applied to a British place of residence, may be accounted for on very rational principles. It is a remarkable fact, that many places in this country have the name of the prince of darkness attached to them

Another British name for 'the prince of darkness' is 'Grim'.

But none of this explains the engineered intricacy of the Holm Hill section of Grimsby serpent mound:

Holm Hill close up. Source: The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby

Rev George Oliver gave us a possible explanation for Holm Hill.

From The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby, p21:

at the time of the Roman invasion, the tides in this country forced their way amidst hills and mountains, so as absolutely to form bays and islands for several miles in land. To no place can this observation of the Roman historian Tacitus apply with more propriety than to Grymsby. It is well known that the influx of waters brought by the tide into the two havens, which were situated on the east and west of modern Grymsby, overflowed the adjacent low lands, and, passing by Holm and Abbey Hills, covered the east marshes on the one side, and the west marshes, Saltings, and part of the common fields on the other

Oliver says the notches in Holm Hill were bays for loading and unloading boats. Given their shape and small size - they look to have been just a few metres across - this seems unlikely. At least for conventional boats. But Oliver also says ceremonies around the mounds included launching 'aspirants' into the estuary in small boats:

...the aspirant, at the conclusion of the ceremony of initiation, was placed in a small boat, to represent the confinement of Noah in the ark... and committed to the waves, with directions to gain a proposed point of land, which to him was a shore, not only of safety, but of triumph. ...the candidate, at the highest time of the tide was committed to the mercy of the waves, from the point now known by the name of Wellow Mill (between Abbey Hill and Sand Hill); and he had to struggle against the declining tide, until he was cast, at the foot of Holm Hill, upon the bank of Ket, the presiding Deity, under whose especial protection he was ever after placed.

If he survived.

We may be able to uncover what Oliver is getting at:

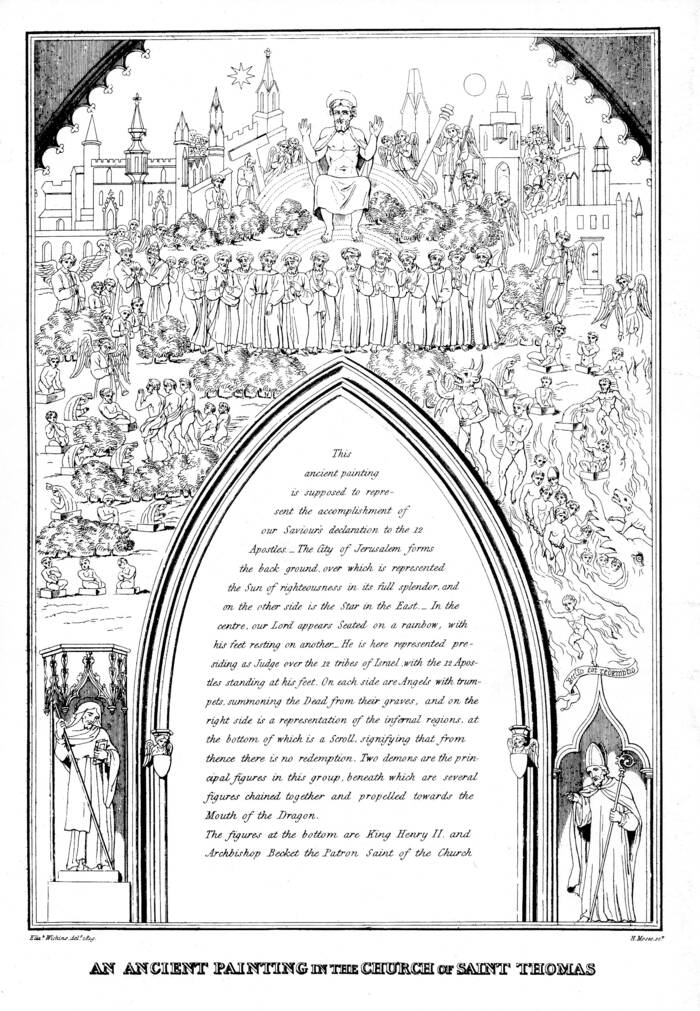

Chained sinners being led to Hell in the Doom painting at St Thomas and St Edmund church, Salisbury. Source 2

New to Doom paintings?

The orthodox explanation of Doom paintings. Source: What is a Doom Painting?

The lefthand sides of doom paintings often show souls rising from under-sized boxes. The orthodox narrative is that the dead are rising from their coffins on the day of judgement. Sometimes they are shown discarding a winding sheet, their death shroud.

Why don't we see ecstatic souls lifting coffin lids? Why do the dead rise from small boxes rather than graves? Why are the 'coffins' painted to appear half in the ground and not at the bottom of graves?

Perhaps because Doom paintings are being mis-described.

Some of England's few surviving Doom paintings depict:

- some coffins as boat-shaped: Chesterton, Cambs, Blyth, Notts, Bacton, Suffolk

- demons carrying anchors or 'weighting stones', or attaching weights to the doomed

- Hell's mouth as the fire and human-stuffed mouth of a sea monster, Leviathan:

- an S-shaped approach to Hell's mouth, as at Broughton, Cambs

Mouth of Hell from St Thomas' Church, Salisbury. Source

So we have Oliver's description of boat-shaped coffins and baskets, Holm Hill's odd shape and the claim it was a launching point for 'aspirants'... We have doom paintings showing boat-coffins, giant serpent-fish, anchors and anchor-stones, and a candidate selection process...

All this suggests something more earthy than divine: living people being cast adrift in tiny boats, all watched over by approving spectactors, some becoming food for sea or estuarine animals.

We should also note, from Great Coates:

Also granted in 1313 (to Lord of the Manor, the Bishop of Winchester, John Sandale) was the right to the manor's 'wreckage of the sea and all animals called waifs, found within the said manor'

In some cases doom paintings appear to have been have been tweaked to help maintain the coffin narrative. Let's look more closely at the St Thomas doom painting for connections with activities at Grimsby.

Below the fish's mouth at St Thomas we see a demon - an 'ellyl' in Grimsby's original language - with an 'alewife'.

Bizarrely, the alewife holding the pitcher is sometimes described as brewer who served half-measures and therefore a sinner being taken to her doom.

The ale-wife from St Thomas' Church, Salisbury. Source

A better fit is that this scene portrays an Ellyl who has sold his human stock for cash. And drunk his earnings. 'Money' having the same root as 'monastery', 'manor' and 'man'. She's not an ale-wife; she's an ellyl-wife. Historically, she shows up as the innkeeper or innkeeper's wife. For example, in a trial from Old Hatfield, Hertfordshire, luridly detailed in The most cruell and bloody murther committed by an Inkeepers Wife, called Annis Dell, and her Sonne George Dell and - until she was censored - in Chester's Mystery Plays.

Analogously, George Orwell opened Animal Farm with a portrayal of drunken Farmer Jones of Manor Farm and his wife.

From The Monumental Antiquities of Grimsby, Grimsby Ellyl Hills chapter, p64:

Notwithstanding their poverty, they are recorded as having been kind and hospitable to strangers (just like 'monks', who were remembered for their ovens); but addicted to excessive drunkenness (just like Lincolnshire's 'monks', according to Oliver), which produced violent quarrels, that frequently ended in bloodshed and death.

It was reckoned a piece of manhood to drink until they were drunk; and there were two men with a barrow attending punctually on such occasions. They stood at the door until some became drunk, and they carried them upon the barrow to bed, and returned again to their post as long as any continued fresh; and so carried off the whole company one by one, as they became drunk.

Wheelbarrow scene from Taymouth Hours, Yates Thompson MS 13, f139v Image source

From Doom (painting):

In yet other cases the Damned are brought into Hell while being forced to ride in wheelbarrows or carried in baskets

As at Bacton, Chesterton, and Yaxley.

We can also see evidence that at St Thomas, the doom painting itself has been modified during the Victorian church restoration era. The right side of the painting may have been modified to look more like land. Compare today's painting with what purports to be a copy of it from around 1800:

The Hell-side of St Thomas's originally had no trees. Source

And, apparently, the trees on the left side have been downgraded to match:

Zealots grabbed all the pruning jobs in God's Garden. Source

Just possibly, someone built Grimsby's mounds as a dock - a Cold Harbour - and occasionally used them to celebrate Mystery Plays. One of several town-sized venues for watching enactments of the Day of Judgement.

Whatever they were for, something intervened, practices changed, and things are looking up for Grimsby now:

Source: The Brothers Grimsby (2016)

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

The Antiquaries Journal, 2 (1922), pp240–254, republished in Journal of Geomancy, Vol II, No. 4 ↩

-

That link also hints at the real identities of 'monks'. ↩

More of this investigation:

Serpent Mounds

More by tag:

#mounds, #Tennyson friend, #human leather