A river of bullshit. Sat 02 December 2023

A blue river of bullshit. Source: A Vanished Industry: Coprolite Mining

Part one of this series exposed the rather suspect narrative of medieval ploughs and unwieldy oxen that supposedly created England's distinctive ridge and furrow patterns. Like most official histories, it turns out to be less about historical accuracy and more about shoveling manure.

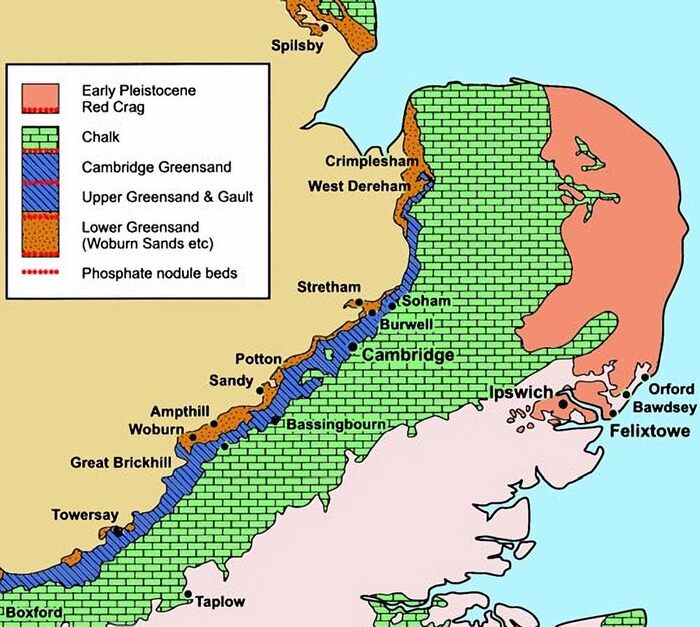

We concluded our first investigation with Robert Liddiard's awkward discovery that Norfolk's ridge and furrow is suspiciously clustered in the west of the county. This cluster sits directly above a specific geological feature: a narrow band of so-called Greensands and Gault clays stretching from Norfolk to Oxfordshire.

That little geological detail wouldn't raise eyebrows if not for what lies along this strip: phosphate-rich nodules that were extensively mined during the 19th century. According to the orthodox narrative, these nodules represented an ancient "river of shit" - fossilized dinosaur excrement that somehow formed a neat, five-mile-wide band across eastern England.

From A Vanished Industry: Coprolite Mining, Trevor D Ford, Bernard O'Connor, Mercian Geologist, 2009:

Phosphatic nodules... occur mainly in... a SW-NE belt from Norfolk to Oxfordshire with outlying patches in Yorkshire and Kent and... Suffolk.

The nodule distribution was noted as being in a belt of country rarely more than 8 km (5 miles) wide along the foot of the Chalk escarpment from Cambridgeshire into Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire, roughly the outcrop of the Gault and Greensand Formations.

How convenient that ancient dinosaurs formed their fecal queue along such a tidy geological line. And how peculiar that this waste matter - normally quick to decompose - managed to fossilize so perfectly along a riverbed, an environment of constant change where fossilization rarely occurs.

Perhaps we're dealing with exceptionally organized dinosaurs with rigid digestive schedules. Or perhaps we're being fed a rather different type of dinosaur product altogether.

Hill and dale: what quarries leave behind

Our first smoking gun comes from an aerial photograph of crop marks at Bassingbourn, Cambridgeshire:

Bassingbourn cropmarks: evidence of medieval farming or industrial activity? Source: 'John O'Gaunt's House', Bassingbourn, Cambridgeshire, Susan Oosthuizen, Christopher Taylor, plate II, p64

Take a good look at the top and right-hand sections of this image. Notice those parallel lines? The caption in the original source describes them as "the remains of the late nineteenth-century coprolite workings." For those of us with less-than-perfect prehistoric fecal pattern recognition, I've outlined them below:

Source: 'John O'Gaunt's House', Bassingbourn, Cambridgeshire, Susan Oosthuizen, Christopher Taylor, p64

These striations aren't remnants of ridge and furrow farming. They remnants of "hill and dale" quarrying.

As explained by Oosthuizen and Taylor:

During the 1880s large areas in the north of Bassingbourn parish were worked for coprolites by the usual 'hill and dale' method (Penning & Jukes-Brown 1881 pp126-9; Fisher 1872; O'Connor 1999).

So here's the awkward question that medieval plough enthusiasts might prefer we don't ask: can you tell the difference between these industrial quarrying patterns and what we're told is ancient ridge and furrow farming? Go ahead, I'll wait while you struggle to find a distinction.

The uncomfortable truth is that they're visually identical. Which raises a rather inconvenient possibility: what if much of England's cherished "ridge and furrow" landscape isn't evidence of medieval farming at all, but the scars of 19th century shallow quarrying operations? What if our quaint agricultural heritage is actually industrial exploitation dressed up in peasant clothing?

Down in the trenches

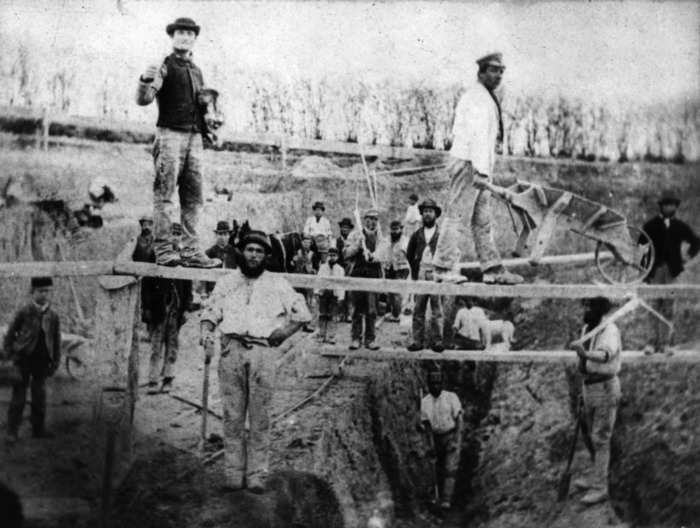

To understand how hill and dale quarrying created these distinctive patterns, we need to examine how the process actually worked. Fortunately, we have photographic evidence from the period when people still remembered what they were really doing:

Orwell, Cambridgeshire. 1860-1870s. Source: Coprolite Mining

Here we see workers excavating a system of trenches, with wooden planks slung across to facilitate the movement of wheelbarrows. It's a busy photograph so I'll describe the bits that matter. Each trench is approximately 1.6m (5ft) deep, with narrower trenches dug into the floors of wider ones. The bottom of the lowest trench sits about 4m (12ft) below ground level.

And yes, it does look like an archaeological dig. In a way, that's exactly what it was: a massive excavation dug for valuables buried beneath.

This trench structure is crucial for understanding how hill and dale quarrying created ridge and furrow patterns. The trenches weren't simply dug straight down; instead, each successive deep trench was offset to one side of the previous trench, creating a stepped system across the field. A system which once backfilled, produces the same profile as ridge and furrow. The same profile that academics attribute to medieval ploughs with supernatural soil-moving abilities.

Another example - from Great Brickhill in Buckinghamshire - shows the same method:

Great Brickhill, Buckinghamshire. Source: Coprolite Mining

Bernard O'Connor's description of the process provides the crucial detail that explains how these trenches eventually created ridge and furrow patterns:

As the coprolite seam was exposed the diggers shovelled it into wheelbarrows or emptied it into trucks. These were then pushed by hand or pulled by horses along a tramway that wound out of the pit, along the edge of the field or trackway to the washmill.

The soil above the seam on the new face was removed after undercutting

and, for convenience, it was just thrown into the trench already worked. This "backfilling" meant that the labourers gradually progressed across the field and onto adjoining property where a new lease was sought. Sometimes pits were opened at opposite ends of the field and two gangs of diggers gradually dug their way towards each other.

Well, would you look at that? This systematic excavation and backfilling created exactly the pattern of alternating ridges and furrows that historians have been attributing to medieval farmers and their gravity-defying oxen teams. As the workers progressed across a field, they partially filled in the previous trench while digging a new one alongside it - creating, in effect, a series of parallel ridges and furrows.

And suddenly, all those peculiar features of ridge and furrow that defied agricultural explanations - the width, the height, the orientation - make perfect sense when viewed as industrial quarrying operations. No more need for oxen with superhero strength or medieval farmers who somehow piled soil several yards sideways and upward.

The Brentingby ramp: a feature no plough could create

Consider this remarkable feature near Brentingby in Leicestershire:

Causeway of the plough-god. Source: Google Maps

What we're looking at is a flat-topped embankment running parallel to a railway line, before turning approximately 60 degrees south and tapering down into a ridge and furrow area. This feature makes about as much sense in medieval farming operations as a smartphone at a jousting tournament. Why would farmers build a ramp into the middle of their ploughed field?

However, it makes perfect sense as part of a quarrying operation. From Trevor Ford and Bernard O'Connor's research:

Processing was sometimes carried out at a single nearby locality using temporary tramroads with horse-drawn trucks running on L-shaped rails.

The embankment is likely the remnant of just such a tramroad, built to transport quarried materials away from the site. This location's physical evidence even suggests the tramway was originally shorter and ended to the west. And that it was extended eastward as quarrying progressed - precisely what we would expect from an industrial extraction operation moving systematically across the landscape.

Here's how those L-shaped rails might have looked:

Tough enough for quarry work. Source: History of the railway track - Wikipedia

Another detail that contradicts the agricultural explanation: ridge and furrow patterns typically run between the shorter sides of each patch. If these were truly the result of ploughing with difficult-to-maneuver oxen teams, it would make far more sense to minimise the number of turns by ploughing in long lines, not short ones. This is the sort of common-sense observation that seems to elude academics with their romantic notions of medieval peasantry.

Recent, not ancient

If ridge and furrow patterns represent 19th-century quarrying operations rather than medieval farming, that would explain why they remain so well-preserved. They're not ancient at all - most are less than 200 years old, barely enough time for the History Channel to film a special about them.

This timeline aligns perfectly with what we know about the coprolite mining industry:

The mining of coprolites (somewhat incorrectly known as fossilised dinosaur dung) provided a short lived economic boom in... approximately 1860 to 1890

It also explains why some obstinate locals insist their ridge and furrow is much more recent than academics claim:

Source: What is ridge and furrow

When farmers tell historians that their local ridge and furrow was created by their great-grandparents - making it less than 150 years old - perhaps they're actually telling the truth. The historical photographic evidence supports this timeline:

Early 20th century ridge and furrow team. Source: Ridge and Furrow

This evidence suggests that oxen teams may indeed have been used in connection with ridge and furrow - not to create it through some mystical ploughing process, but to spread topsoil and, well, bullshit, over the trenches left by hill and dale quarrying. They made the top level of soil suitable for subsequent cultivation while leaving behind the distinctive pattern we still see today.

The stately home paradox

Perhaps the most telling evidence against the medieval farming explanation comes from the grounds of England's stately homes. These meticulously landscaped estates, often completely remodeled in the 18th century by luminaries like Capability Brown, should have obliterated any traces of medieval farming. Yet puzzlingly, many contain perfectly preserved patches of ridge and furrow.

Take Burghley House near Stamford, site of what was allegedly Brown's largest and most radical landscaping project:

Ridge and furrow (just) visible in Burghley House landscaped park.

The ridges and furrows are more clearly visible viewed against the hedge line:

Ridging highlighted against fence and woodland plantation.

Although they are hard to see from above, it's just possible to make out the neat rectangular patch of ridge and furrow sitting incongruously in the midst of Brown's carefully designed landscape:

Click on the image to see it bigger and clearer. Source: Google Maps

Burghley House is just out of shot to the right.

Why would Capability Brown, renowned for his meticulous attention to detail and obsession with creating the perfect English landscape, preserve patches of medieval farmland in his grand design? The answer, of course, is that he wouldn't. These patterns almost certainly postdate his landscaping work - which is a rather awkward fact for the medieval farming narrative.

Similarly, in Leicestershire, Stapleford Park's extensively remodelled 500-acre grounds contain neat patches of ridge and furrow just south of the main house:

Ridge and furrow at Stapleford Park house. Source: Google Maps

Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, whose grounds were completely re-landscaped in the 18th century, also shows ridge and furrow patterns in front of the house:

How did ridge and furrow survive Chatsworth's landscaping? Source: Shadow Rome - III: The Earth Movers

The traditional explanation for ridge and furrow simply cannot account for these anomalies. But if these patterns represent 19th-century quarrying operations, specifically targeting the locations of earlier structures to salvage valuable materials, then their presence in carefully landscaped grounds makes perfect sense.

Understood in this way, small patches of ridge and furrow in bigger fields and stately home gardens becomes explainable. And individual ridge and furrow patches that run counter to conventional explanations can be seen for what they really are: the scars of resource extraction.

Examples:

Grounds of Gunthorpe House. Source: Google Maps

Many ridge and furrow patches are shaped like a stretched hexagon. Often with the lines of ridge and furrow running between the shorter sides not between the longer sides.

A mile south of Oakham, Rutland:

Near Manton, Rutland. Source: Google Maps

Many are lone little patches, often next to a road or railway line:

West of Thistleton. Source: Google Maps

Sometimes they are lone patches within larger boundary lines kept company by oddly-shaped tree plantations and 'fish ponds'. All of these hint at infrastructure quarried out, then covered up. The roots of tree plantations helpfully destroy stone foundations of ruins not worth the effort of quarrying:

1.6km north-east of Kirby Hall, Deene, Northampstonshire. Source: Google Maps

The nature of the beast: what was really being quarried?

If we accept that much of England's ridge and furrow landscape represents industrial quarrying rather than medieval farming, we must ask: what was actually being extracted?

I'm not suggesting that England's stately homes were being mined for "fossilized dinosaur shit." Rather, the evidence points to the recovery of valuable materials from earlier structures - metals like lead, copper alloys like brass and bronze, perhaps gold and silver, along with tiles and cut stone. All items with considerable salvage value, especially when you're not paying their original owners.

The very geology associated with these quarrying operations raises additional questions. The so-called "Greensand" (green being the color associated with copper contamination) and "Gault clay" (a name suspiciously similar to "gold") suggests the true nature of what was being extracted may have been quite different from the official narrative of dinosaur droppings.

Even the terminology is revealing. As Bernard O'Connor notes:

Fourteen different variations have been found in the 1861-1891 census data. They include coprolite, copperlight, copperlight, copperlite, coupperlite...

It was Rev. William Buckland, the Dean of Westminster and the first professor of Geology and Mineralogy at the University of Oxford, who coined the word Coprolite.

Yes, the same Buckland who formulated the idea that a five-mile-wide river of fossilized dinosaur excrement ran across eastern England. A story that defies basic principles of fossilization:

From How Fossils Are Really Formed:

It turns out the textbook explanation is wrong.

Fossils are actually formed by a cataclysmic event that includes widespread catastrophic flooding. The silt-laden flood water washes indiscriminate amounts of wildlife into an area where they collect and are buried immediately and deeply.

The term "coprolite" itself appears to have undergone a certain linguistic sleight-of-hand. Note the censuses recording variants like "copperlight" and "copperlite" - suggesting the material being extracted was associated with copper, not coprolites. This kind of linguistic transformation is a common technique for obscuring the true nature of historical activities.

Transport networks hidden in plain sight

The hill and dale quarrying explanation also illuminates other landscape features that have been historically obscured. Consider Exton Park:

Ridge and furrow at Exton Park. Source: Google Maps

The ridge and furrow patch northeast of Exton Hall aligns with a "ride" that continues in the same direction as a path between trees. The notion that ridge and furrow masks removed transport infrastructure throws light on accounts from Gas Stations of the Past - Part Three, which presents evidence that certain historical journeys must have been assisted by now-vanished transport infrastructure.

Rawnsley and Farguharson's improbably lengthy "walking" journey from Exton Park hall to Grimsthorpe Park makes considerably more sense if they were travelling along now-removed transport infrastructure - the traces of which remain in our landscape as ridge and furrow and these connecting "rides."

If you're struggling to understand how the ridge and furrow cover up fits into IHASFEMR, try seeing yourself from outside the box.

Try seeing yourself as someone else who struggles to recognise transport infrastructure:

Does ridge and furrow look like anything to you? Source: Westworld

If these revelations are a bit harrowing, don't feel too bad. Ridge and furrow in England is subtle compared to ridge and furrow in Namibia:

Western Kalahari, Namib Desert. Source: Kalahari Desert - Wikipedia

From Namib - Wikipedia:

Southern Namib (between Lüderitz and the Kuiseb River) comprises a vast dune sea with some of the tallest and most spectacular dunes in the world, ranging in color from pink to vivid orange. In the Sossusvlei area, several dunes exceed 300 meters (1,000 feet) in height. The complexity and regularity of dune patterns in its dune sea have attracted the attention of geologists for decades, but it remains poorly understood.

They don't look like anything to geologists.

They might do better if geologists considered the resemblance of 'Kalahari' to "Kali's Harrow".

Conclusion: an industrial cover-up of almost medieval proportions

The evidence presented in this two-part series suggests that England's ridge and furrow landscape is not primarily the result of medieval farming practices, but rather the scarring left by 19th-century shallow quarrying operations. This industrial activity targeted the remains of earlier structures and infrastructure, extracting valuable materials while literally burying the evidence of what came before.

The supposed "river of fossilized dinosaur excrement" provides a convenient cover story for what appears to have been a systematic program of resource extraction - one that has been deliberately misattributed to medieval agricultural practices. After all, who wants to admit they're digging up the past for profit when they can claim to be preserving it?

This reinterpretation resolves the inconsistencies identified in part one of this series. It explains why ridge and furrow patterns run counter to efficient ploughing practices, why they appear in recently landscaped stately grounds, why they're suspiciously well-preserved, and why they're clustered along specific geological features.

It also raises profound questions about what exactly was being recovered from beneath England's surface in the 19th century, and why the true nature of this industrial activity has been so thoroughly obscured behind a façade of medieval farming and fossilized excrement.

The lie of the land, it seems, goes deeper than we thought. But perhaps not as deep as the material that was extracted from it.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

More of this investigation:

The Lie of the Land,

More of this investigation:

Writing Past Wrongs

More by tag:

#enigmatic landscaping