Mausoleum design suggests gas creation, storage and management. Sat 04 December 2021

Inside the Philipson mausoleum, Hoop Lane cemetery, London. Source

Seemingly, the Philipson Mausoleum has little or no space for coffins. Perhaps they are on the camera side in this image of the mausoleum. But note how its floor look like a pool? See the drain in the centre?

Water and gas-related infrastructure shows up surprisingly often in and around mausoleums.

Such as valves and drains:

Metal item lying in front of the Dennis mausoleum, Clonbern, Co. Westmeath, Ireland. Source: The Mausolea & Monuments Trust

Note the rod-like affair in the centre of the metal item at front.

This metal item used to be attached to top of the Dennis mausoleum:

Dennis Mausoleum's metal item before it was removed. Source: The Mausolea & Monuments Trust

Note the different lengths of the item's two handles. One of them looks a little like a lever handle.

A bit like this handle:

Source: Pinterest

We used to be familiar with cast iron valve handles. They were everywhere.

But the assembly formerly atop the Dennis mausoleum has no water spout. And it was in the wrong place for releasing water.

It looks more like a gas release valve.

In the scenario I'm proposing, lighter-than-air gas flowed out automatically when the long handle was push in towards the valve body.

Unlike hot air balloons, gas balloons were filled through long fabric tubes. The blue and white striped balloon below is set up for refilling:

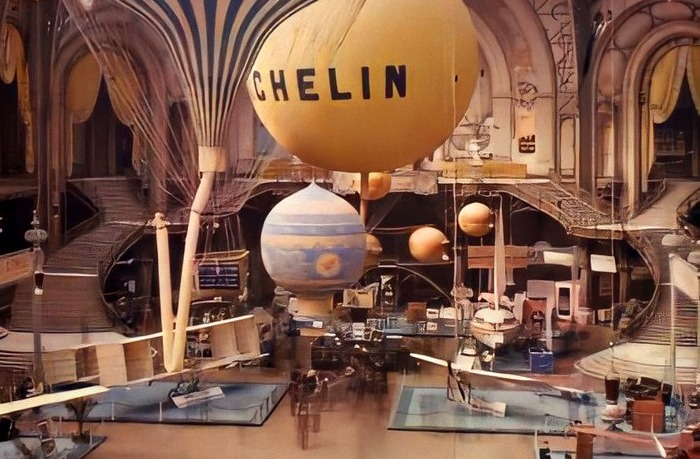

Paris Air Show, September 1909. Source: StolenHistory.org

To the right of it, just visibly, the yellow Michelin balloon also looks set up for gas refilling.

The valve was probably opened by rigid, weighted ring at the bottom of the balloon or dirigible's refill tube. Perhaps when the tube was lowered over the valve, the ring eventually pushed the valve handle in, releasing the gas to flow up the tube.

Ireland's Dennis mausoleum is the only (known) surviving cast iron mausoleum in Ireland and Britain. Cast iron doesn't produce sparks when scraped against iron or other metals.

Not that corpses care about sparks, but flammable gasses do. So most mausoleums were built from stone.

In south-west London's Brompton cemetery, the Courtoy mausoleum also shows evidence of valves having been removed:

Bolt-holes around the occuli of the Courtoy mausoleum, Brompton cemetery, London. Source: The Mausolea & Monuments Trust

Note the bronze door. Like cast iron, bronze doesn't produce sparks when metal scrapes against it.

Many, many 'mausoleums' have circular orifices high on a wall or roof.

Although some of the Courtoy mausoleum's technology has gone, local folklore remains. It claims the Courtoy mausoleum was once used for teleportation or time travel.

See:

It's possible to see how producing gasses for lighter-than-air travel earned the mausoleum a reputation for assisting teleportation, but how did it acquire a reputation for time travel?

Some 'folklore' was created to dilute memories of removed technologies. To smear memories into memories of things that weren't. More evidence of this technique is presented in the 'Ice Age Sites of Britain's Serpents' series.

That's two mausoleums with the remains of what appear to be gas valves. What about drains in mausoleums?

That some 'mausoleums' housed water-baths with sophisticated control systems - at least from a corpse's perspective - is also most obvious at the Philipson mausoleum:

Interior floor of the Philipson mausoleum, Golders Green, London. Source: The London Dead

The greenish central structure is a bowl-shaped drain, a plug-hole without a plug. It sits in the centre of a large circular bath that takes up most of the mausoleum's floor:

Philipson mausoleum funnel drain. Source: Simon White

Obviously, the Philipson mausoleum collected water in a bath and drained it. Why let water into a mausoleum in the first place? A bit strange for a mausoleum, no?

It's hard to tell how common the bath-plus-drain mausoleum structures once were. Possibly a lot more common than we think. Because water collection structures show up in very unexpected places.

The top of an Ely Cathedral tower is one usually invisible example:

Water funnel atop Ely Cathedral, Cambridgeshire, England. Source

If you're collecting water, you have to drain excess water:

Left: apparent drain hole in side of the Dartrey mausoleum, Black Island, Co. Monaghan, Ireland. Source: The Mausolea & Monuments Trust

Plans for the Philipson mausoleum structure in Surrey County Council's archive show it was designed to maintain water at a predetermined level in its bath. Its drainage system was designed to keep the bath about one-third full:

Drain on the left; water level control on the right. Source: Surrey County Council

You can think of that vertical pipe on the right as working like a mini-weir or the U-bend beneath a kitchen sink.

The bath is the single largest container in the Philipson structure. Apparently, it turned water and - presumably 'bio-waste' - into a shallow, artificial marsh. Marshes produce lighter-than-air hydrogen, helium and methane gases.

In the Philipson mausoleum the gasses would have collected under the dome at the top of the structure.

Like some other mausoleums, Dartrey's internal decor focuses on flying and 'ascension'.

Dartrey mausoleum interior inscription. Source: The Mausolea & Monuments Trust

Michelin's presence at the 1909 Parish Air Show offers more clues to this forgotten complex of technologies.

Rubber balloons were often made from a mix of rubber latex and mistletoe juice (called bird-lime).

From Forty Years of a Sportsman's Life, Claude Champion de Crespigny, 1910, p134:

On Monday, July 30, 1883, Simmons... came to Maldon with his balloon, and at once set about repairing some damages which it had sustained at Brighton a few weeks previously. Composed principally of indiarubber and bird-lime — a queer combination this must seem to the non-aeronautic mind — it was one of the strongest balloons ever constructed. It was capable of holding 37,000 cubic feet of gas, — exactly the same quantity, by the way, as held by the balloon in which Burnaby crossed the Channel, — and when inflated it was seventy-five feet in height and forty-two in diameter.

Bird-lime = an adhesive made from the juice of mistletoe berries.

How did they make these balloons?

The same way party balloons are made: by painting latex on to a form:

And letting it dry upright. Source: BALLOONS | How It's Made

They really made 37,000 cu ft gas balloons this way?

No.

They probably made them this way:

Cooke mausoleum, Reynella, Ireland. Source: The Mausolea & Monuments Trust

Mass production of balloons only began in the 1930s. Before then, balloons were made individually. Big ones on big, upright forms.

From Cooke Mausoleum - The Mausolea & Monuments Trust:

Constructed by Adolphus Cooke (1792-1876)... to house the remains of his father, Robert. Adolphus Cooke had a strong belief in reincarnation and designed the mausoleum in the form of a bee skep as he believed his father would be reincarnated as a bee.

Presumably that's 'bee-for-balloon'. Like I said, a lot of 'folklore' was deliberately created to set you buzzing up the wrong flower.

If the Cooke Mausoleum were really a mausoleum, it would at least have a coffin-sized door, not this undignified crack:

A door only bees could love. Source: Buildings of Ireland

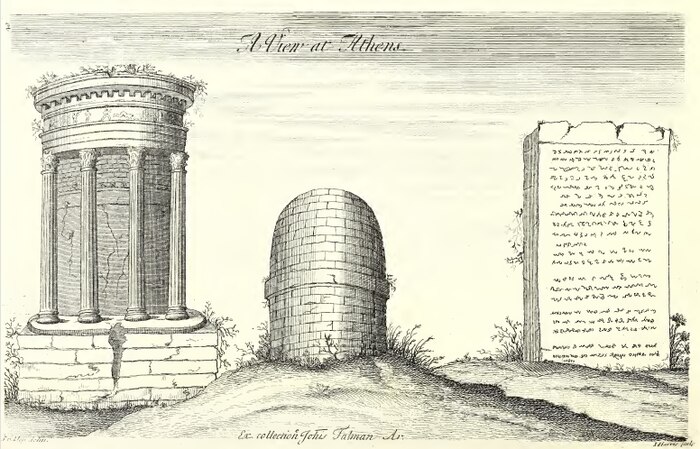

Antiquarian William Stukeley also hinted that balloon forms and mausolea gas production facilities once went together:

Source: Itinerarium Curiousum

The rib section around the strange central structure suggests balloons made on this form were moulded to receive an internal hoop after they removed from the form. Overall the form looks more suited to producing the thick-waisted balloon visible at the rear of the Paris Air Show image shown above.

Assuming Stukeley knew what this engraving really represented, we can conjecture that several adjacent engravings in Itinerarium Curiousum also present hidden meanings:

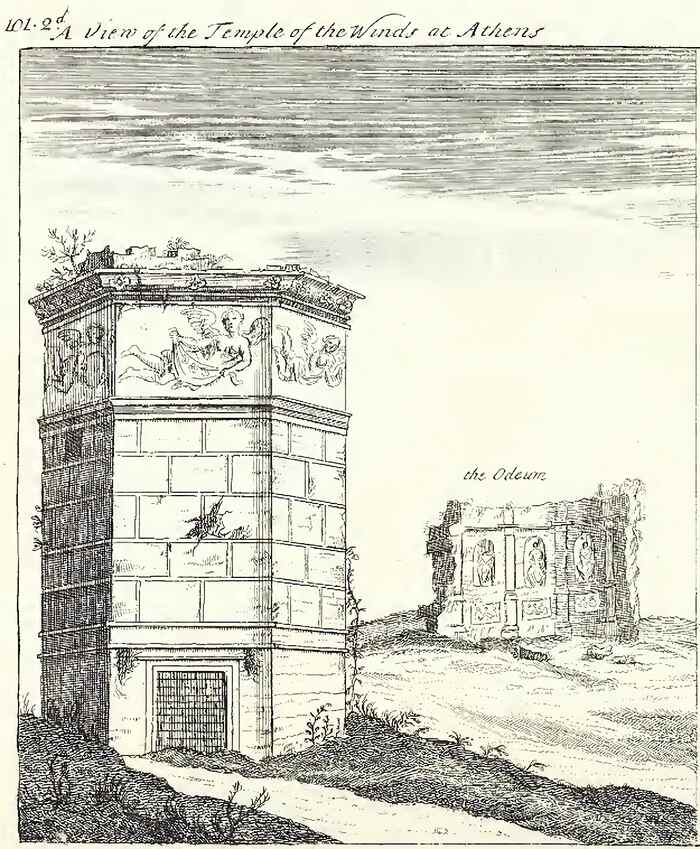

Mausoleum next to The Odeum. Itinerarium Curiousum

Note the winged angels on the 'mausoleum'. Note the possible connection between Odeum and odour?

This engraving is titled: A View of the Temple of the Winds.

Get his joke?

Germans will. 'Fahrt' means 'drive' or 'travel' in German.

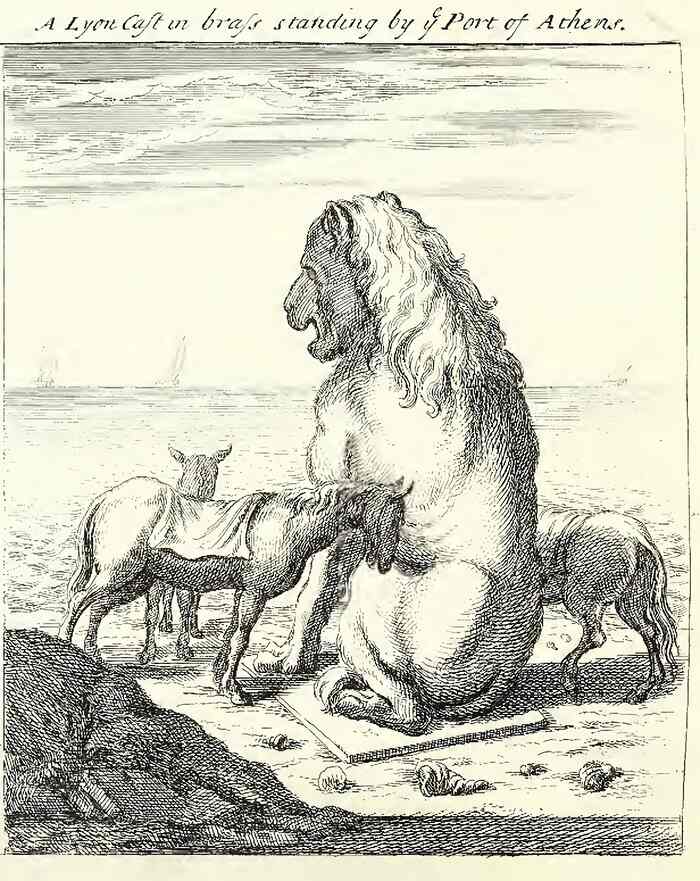

Slightly more enigmatic is the engraving next to it:

Lion, pony, ass. Source: Itinerarium Curiousum

These animals seem disconsolate. As if out of work. But in the context of Stukeley's imagery as balloon-related imagery, we have clues about what the ass might represent.

From The local historian's table book, of remarkable occurrences, connected with the counties of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland, and Durham. Historical division, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, November or December 7, 1733:

A flying man flew from the top of the castle of Newcastle into Bailiff-gate, and after that he made an ass fly down, by which several accidents happened, for the weights tied to the ass's legs knocked down several, bruised others in a dreadful manner, and killed a girl on the spot. — Newc, Cour.

Just as structures once used for making and gassing balloons are now presented as archaic structures for housing the dead, so words once used for different lighter-than air technologies have also acquired new meanings. Perhaps balloons designed for speed and carrying post (the pony), balloons for carrying loads (the ass) and balloons designed for warfare (the lion).

Just a guess.

If you were making 'asses' to help builders lift heavy loads up the sides of buildings, you're probably not going to sell them zeppelins or big globe balloons.

You'd offer smaller balloons fitted with equipment to keep them in place on your building site.

Take another look at the Parish air-show image above. At the back of the show hall.

At this part:

Four low-load cargo balloons behind 1909 Michelin exhibit.

Those four small balloons repay close inspection.

Enlarged again:

Note how the two most clearly visible small balloons each have two lugs built into their sides, one lug above the other. At the Paris Air Show, the lugs seem to have been threaded on to vertical poles or cables.

Ideal if you want to lift loads up the sides of buildings.

To move a load around, you could just tie a load to the lugs to reduce the apparent weight of the megalith stone, then move it by hand or cart.

Lugs...

Legs...

Looking again at The local historian's table book, of remarkable occurrences, connected with the counties of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland, and Durham. Historical division again:

the weights tied to the ass's legs knocked down several, bruised others in a dreadful manner, and killed a girl on the spot.

If you needed balloons to lift heavy loads in narrow spaces like a street, you might produce balloons that were long and thin. Like the long party balloons that clowns fold into animal shapes.

How might the forms - the moulds - for this type of balloon look?

Lingam and spout. Source: Unseen Cave Temple of Shiva? Sathrumalleswaram, India

He says: "It's nicely polished for the liquid poured down it?"

If you made a cargo cult of pouring latex and plant-based additives on to a balloon former, how might it look?

Source: Live Darshan - Shree Mahakaleshwar Temple Ujjain (महाकालेश्वर मंदिर के लाइव दर्शन)

That might account for how heavy loads were raised. However, many loads need to be carried along.

A curious aspect of travel in the past is that some accounts suggest people were travelling quite fast and/or travelling beyond the endurance of the horses they were allegedly riding.

From The Torrington Diaries (Abridged Selection), John Byng, allegedly 1791, published in 1954, p335:

Tho' yet, the posting on horseback might have been very quick; as we know from several accounts ; particularly in that entertaining life of Henry Carey Earl of Monmouth. 1

'Who to outstrip his fellows, and gain the favor of the new Monarch - set out from Whitehall betwixt 9 and 10 o'clock in the morning of March 24th, 1603, and reach'd Doncaster that night.'

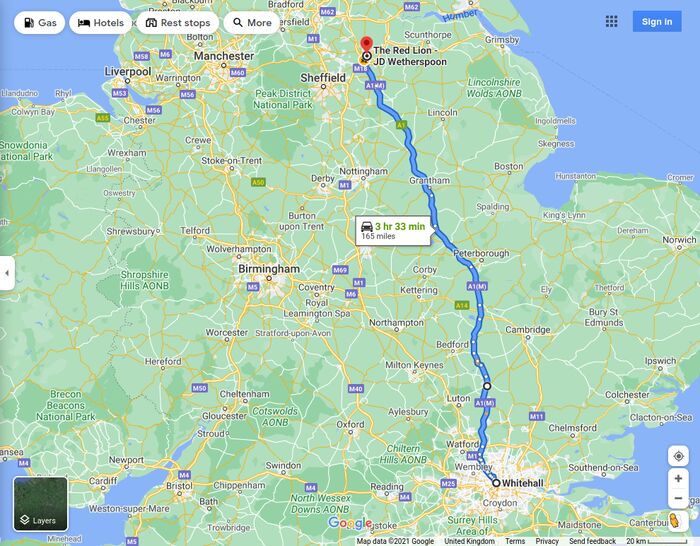

This is a map of - roughly - Carey's 195 mile route:

Whitehall to Doncaster route today. Source: Google Maps

Assuming 'that night' means at 21:30 and the route was more or less as it is today, then Carey rode 195 miles in 12 hours in late winter.

That is 16.25 miles per hour.

From How Far Can A Horse And Rider Travel In A Day:

Under these optimal conditions, you can expect to walk around 20 miles. If you mix in some trotting and cantering throughout the day, you might cover up to 30-40 miles.

If so, then to cover 195 miles, Carey must have changed horse seven times. So adding in change times, he must have have riddent them faster than 16.25 miles per hour.

And that's assuming the roads of 1603 England met that writer's definition of 'optimal conditions'.

Carey's journey is either highly unlikely or 'horse and carriage' meant something different in 1603. Evidence for another possibility for what it meant is collected in Location Analysis: Peterborough-Stamford Wild Hunt

Similarly, 'walking' seems to have meant something different until very recently.

Typically, a modern person can walk about 20 miles in a day. A 26-mile marathon on modern London's traffic-cleared roads takes about four hours.

But walking 20 miles a day on modern roads on ten consecutive days takes a rare level of fitness. Yet in the past it seems to have been possible.

From Colonel John Byng's Journey into Sussex - 1788:

Byng did have a companion for his journey, a long-standing friend who is only ever identified by his initials, I.D.

This gentleman preferred to walk rather than ride. As the journey lasted ten days and covered two hundred and five miles he must have been pretty fit.

Given the volume of food and drink John Byng and I. D. consumed - not to mention their sight seeing and artefact collecting - their 20 mile-a-day average is remarkable. As is the fact that they were travelling different routes much of the time. This implies a multiplicity of good routes were available so they could reliably meet up again at the end of the day.

Again, the suspicion is that they were each using different routes and have been riding on high quality roads.

Yet some people seem to have been able to walk even further than 20 miles in a day. Almost three times further.

From Highways and Byways in Lincolnshire, Rawnsley and Farguharson, 1915, p35:

I once walked with an Undergraduate friend on a winter's day from Uppingham to Boston, about 57 miles, the road led pleasantly at first through Normanton, Exton and Grimsthorpe Parks, in the last of which the mistletoe was at its best ; but when we got off the high ground and came to Dunsby and Dowsby the only pleasure was the walking, and as we reached Billingborough and Horbling, about 30 miles on our way, and had still more than twenty to trudge and in a very uninviting country, snow began to fall, and then the pleasure went out of the walking. By the time we reached Boston it was four inches deep. It had been very heavy going for the last fourteen miles, and never were people more glad to come to the end of their journey.

Note the interest in mistletoe.

Here's that 57-mile walk mapped against the approximate 20 miles a day that a healthy modern person can typically walk:

A mostly roadless day's walk

Key:

- Blue marker: Rawnsley and Farguharson's waypoints

- Green line: Rawnsley and Farguharson's one-day walk

- Red line: Typical modern person's one-day walk

As we have seen, he probably had good reason to take note of mistletoe sites. 2

So, how difficult is it to walk 20 miles every day for 10 days like Byng's companion I. D? Let alone 57 miles in a day?

From Goddess Nessat. Or, it all depends on your point of view, Igor the Greek:

[The Peace March] is an annual competition that has been held since 1909. International military delegations and professional athletes from all over the world take part in it. They need to cover a distance of 160 kilometers (99.4 miles) in 4 days. Movement is allowed only on foot.

Once again: the task is to walk 160 kilometers in 4 days, 40 kilometers per day . (!!!)

That's 25 miles per day.

Apparently, many Peace March competitors drop out.

Yet in addition to claims about Carey, Byng's friend I. D. and Rawnsley/Farqueson's 57-mile walk, official history makes the following claims about 18th century armies:

From Goddess Nessat. Or, it all depends on your point of view:

Allegedly in 1765:

When [A.V. Suvorov] was ordered to go with the regiment from Petersburg to Riga...

Having put one platoon on carts and taken with it the full treasury and the banner, he arrived in Riga in eight days and from there reported by express about the day of the regiment's arrival at the place assigned to it in a report to the Military Collegium, which was amazed at such haste. Soon the rest of the regiment arrived, but not in thirty days, as prescribed by the route, but in no more than fourteen days. Military Notes, D.V. Davydov

And again three years later:

The order for the Suzdalians to march to Smolensk in November 1768...

The regiment marched from Ladoga to Smolensk in the dead of autumn, during the thaw. (sic)

Suvorov made full use of this march through difficult terrain, through forests, swamps and rivers, to replenish the training of the men, familiarizing them with all the details of military marching, which he was unable to do during his peaceful stay in Ladoga.

The Suzdalians... easily covered over 850 miles in 30 days, without any stragglers and almost no sick people. Military Notes, D.V. Davydov

In late autumn, during the muddy season, through rivers, forests and swamps!

Igor the Greek doubted these official claims were true.

But with so many construction details of mausolea and lingams left unexplained, perhaps we should pay a little more attention to the technologies of the mistletoe-obsessed 'flying men' and their flying asses:

George Lewis watercolour circa 1890. Source: Daily Art Magazine

More on anaerobic decomposition:

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

The footnote says Byng got Carey's first name wrong: This is a mistake in the Christian name. It is Robert Carey, 1st Earl of Monmouth (1560-1639), who recounts the journey in his Memoirs. ↩

-

Rawnsley and Farguharson's 'walk' must have been assisted with technology. Noting that they stopped at halls ('halts') in three parks ('park', 'stop', 'halt'), it's conceivable they were 'walking' a tram road. Examining the terrain around their route between Exton Park and Grimsthorpe Park reveals several clues to removed former transport infrastructure. ↩

More of this investigation:

Gas Stations of the Past,

More of this investigation:

Misunderstood Technology

More by tag:

#human fat