Ridge and furrow looks like a cover up. Fri 01 December 2023

The lie of the land. Source: Medieval Ridge and Furrow above Wood Stanway

Location: Wood Stanway, Gloucestershire: Google Maps

If you weren't already familiar, then:

Source: Ridge and Furrow

Fortunately, experts have answers:

It was primitive ploughs and unwieldy oxen. Source: Into the picture podcast: Ridge and Furrow

Unfortunately, their answers only furrow more brows. Especially if you've actually read What is Medieval Ridge and Furrow and appreciated the volume of bullshit involved.

Primarily they imply medieval plough-boys ploughed the same furrows year in, year out, planting grains on the well-drained ridges and water-loving crops in the wetter furrows year in, year out.

But any vegetable farmer knows that's unlikely. The practice would deplete both your soil's fertility, its plough-ability (by producing hard pan) and its water handling ability.

You'd starve before you discovered crop rotation. Or bog down in the bottom of your waterlogged furrow.

The contradictions generated by ridge and furrow's explanations may explain why experts have developed many more explanations for ridge and furrow's riddles. Explanation from which more contradictions sprout like weeds.

Take for example the orientation of ridge and furrow:

They're always on contour. Source: What is ridge and furrow

She says they're always across the contour but then describes them as if they were on contour. Which some are.

But not these:

Suitable for cactus at the top, water lillies at the bottom. Source: Old Rigg and Furrow Arable Farming - Landscape Archaeology

Or try this contradiction:

No caption necessary! Source: Ridge and Furrow

Who knew all farmland in England is ploughable north to south, with the contour and across it, all the while following the lie of the land?

Presumably not the yokel who ploughed this:

Check the patch top-right. Why? Source: Cotswolds Ridge & Furrow Farming

Or the one at the top of the page.

Both the above image and the Wood Stanway image at the top of the page prompt an important question: if ridge and furrow really demonstrates the difficulty of turning old ploughs and oxen teams around, why did they plough short strips?

They would waste a lot less soil, time, animal management and equipment wear if they ploughed the longest possible strips.

And how did they even turn an ox team around without damaging the neighbouring ridge and furrow?

Expert explanations for the height and width of ridge and furrow are less amusing than explanations for its orientation. They lack the amusing contradictions. Instead, explanations for ridge and furrow's height and width are amusing because they contradict universal natural forces like gravity.

And - albeit less universal - commonsense.

From Cotswolds Ridge & Furrow Farming:

Surviving ridges are parallel, ranging from 3 to 22 yards (3 to 20 m) apart and up to 24 inches (61cm) tall – but were up to six feet tall when in use.

Six feet tall? Two metres high?

Were these oxen ploughing fields or ploughing mass-graves?

Actually, many of them probably were mass-graves. But that's for later. For now, just note that the super-oxen of yesteryear and their primitive medieval ploughshares could apparently plough a gradient that was up to six feet higher on one side than the other.

With that gravity-defying soil management in mind, let's return to Cotswolds Ridge & Furrow Farming and its comments about ridge and furrow's width:

Got it: eight yards on average. Source: Ridge and Furrow

If - as is usually claimed - medieval families sowed on both the ridge and in the furrow, how did they prepare an eight-yard wide ridge for sowing?

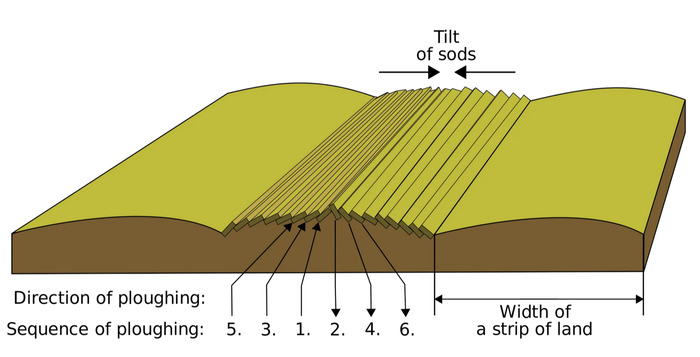

Perhaps we're to believe that they layered their up-to-six-feet-high-ridges in the way shown in the diagram below:

It's a tilting sod. Source: What is Medieval Ridge and Furrow

But that can't be right because experts attribute the 5, 8 or 11-yard wide ridges to the wide turning circle required by a team of oxen. So how were they turning the teams to plough soil between the ridge and furrow without leaving traces of the turns?

It's not worth trying to answer the question because the 'medieval agriculture' explanation is a cover up. A cover up made of bullshit.

To be fair, some experts do admit ridge and furrow isn't quite the settled science it is portrayed to be:

Though they tend to live in prosperous economies. Source: Lauresham digital - Ridge and Furrow Research project

In Britain, one brave expert did admit ridge and furrow doesn't stack up.

Robert Liddiard set out his concerns very carefully, perhaps even delicately. So I've used AI to simplify what he said.

In East Anglia, strips were usually ploughed flat, unlike in the Midlands, where they were cast up to form ‘ridge and furrow’ (Goudie, 2020). The survival of medieval ridge and furrow in England, including East Anglia, is notable in regions where the land has not been extensively ploughed or developed since the Middle Ages (RuralHistoria, 2023).

This quote implies ancient east Anglians never fell for the allegedly Roman oxen-pulled plough-share that created ridge and furrow everywhere else. No, they possessed an alternative plough-share. A plough-share that didn't pile up soil.

It's curious this technology didn't spread to the beleaguered Midlands, where - apparently between 440 AD and the 1800s - they wasted titanic amounts of oxen energy ploughing ridges up to 2m (6 ft, 6 in) high.

If that ludicrous scenario is true, it's no surprise medieval Midlands farmers eventually abandoned the plough for sheep and dairy pasture. Their disdain for ancient ploughing technologies might explain why so much ridge and furrow is visible in the Midlands today.

Liddiard didn't fall for this bullshit. He studied the fingerprints left by East Anglia's medieval miracle farming technology.

Here he summarises just a couple of the problems he encountered:

From The distribution of ridge and furrow in East Anglia: ploughing practice and subsequent land use, Robert Liddiard, Agricultural History Review, 1999:

some aspects of the practice are not clearly understood.

Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire retain relatively few examples of ridge and furrow. [And] There is an uneven distribution across the three counties, despite the fact that during the medieval period, open-field agriculture was ubiquitous.

Liddiard attributed the disparity to the enthusiasm of the region's modern farmers. He thought when new ploughing technology emerged - that would be the horse, then the tractor - East Anglian farmers had joyfully ploughed away most of their ridge and furrow.

The theory seems reasonable - especially if you consider East Anglians didn't have much ridge and furrow to begin with.

But that does raise the question: why did anybody else fall for it?

If you read Liddiard's paper, you may intuit he wasn't very convinced by his own argument. Perhaps he was trying to keep his job.

Helpfully, Liddiard mapped the uneven distribution of ridged and furrow in East Anglia. He even mapped Norfolk's remnant ridge and furrow against its pasture lands.

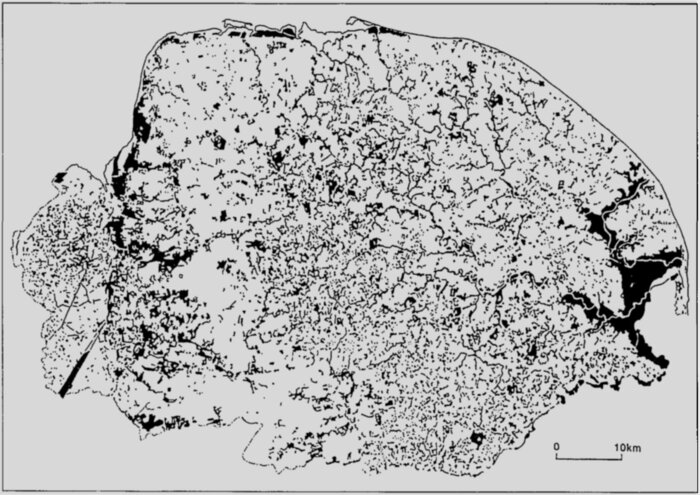

Here's his map of Norfolk's pasture land:

Black shows Norfolk's pasture land in the decade prior to 1938. Source: The Distribution of Ridge and Furrow

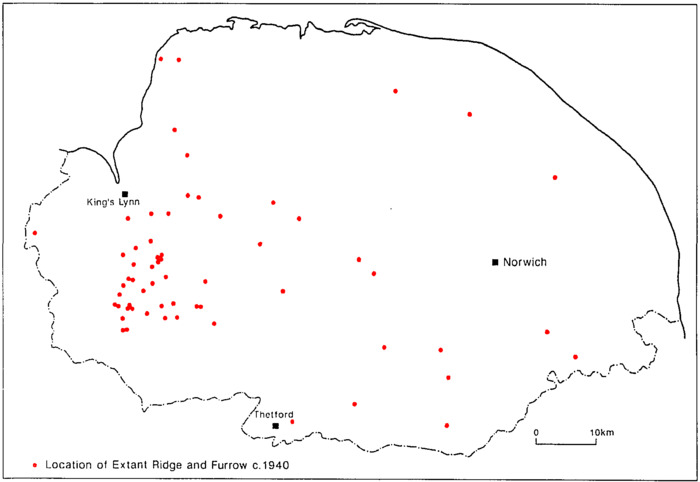

And here's his map of Norfolk's remnant ridge and furrow. The red blobs denote patches of ridge and furrow:

Norfolk ridge and furrow as surveyed around 1943. Source: The Distribution of Ridge and Furrow

Not much correlation.

As Liddiard already knew, Norfolk didn't have much ridge and furrow. But what ridge and furrow there was should have correlated with Norfolk's pasture land. On the basis that no matter how they ploughed it, farmers of any era prefer to plough flat, fertile pasture land.

As Liddiard's second map shows, what ridge and furrow remained in Norfolk was certainly on pasture land but it was clustered in the west. While Liddiard's first map showed pasture was much more widespread across Norfolk, especially to the east.

Liddiard attributed this non-correlating cluster-muck to a theory that could be described as: "the eastern East Anglia was an early adopter of superior non-Roman/non-medieval ploughing technology" theory. It claims modern farmers in east Norfolk machine-ploughed away any remnant ridge and furrow. Liddiard half-heartedly proposed this modern ploughing had struggled in west Norfolk compared to earlier ploughing technologies - and that was why more ridge and furrow remained in the west.

But as far as anyone knows, Norfolk's farmers didn't have beta-tester access to tractors. And west Norfolk's ridge and furrowed pasture is just as ploughable by tractors as pasture in any other part of Norfolk.

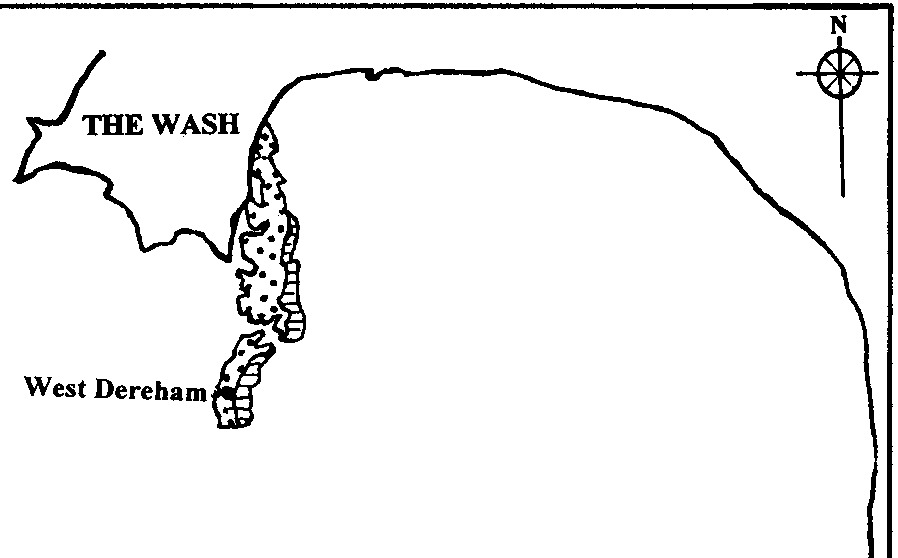

But the red-faeced blobs of ox-shit - OK: ridge and furrow - on Liddiard's second map do roughly correlate with something else:

West Norfolk's Gauld was worth digging for. Source: The Origins and Development of the British Coprolite Industry

The patch of geology beneath west Norfolk's ridge and furrow is 'Greensand' and 'Gauld' clay. This map suggests the presence of ridge and furrow depends on what was buried underground and not what was ploughing the ground.

This correlation may help unlock a better understanding of what ridge and furrow was really about.

And the real origin of ridge and furrow.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

More of this investigation:

The Lie of the Land,

More of this investigation:

Writing Past Wrongs

More by tag:

#enigmatic landscaping