A carefully described serpent mound. Which didn't make it into Scotland's Canmore database of ancient sites. Thu 21 April 2022

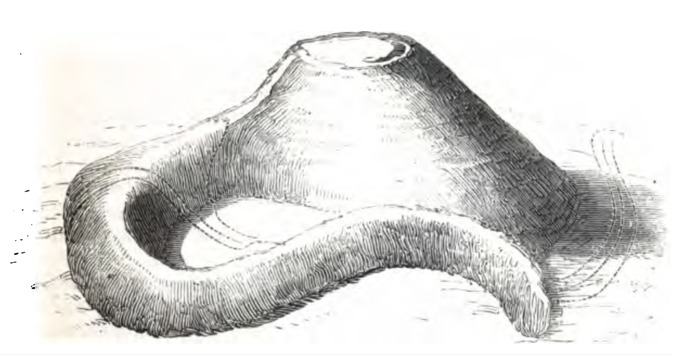

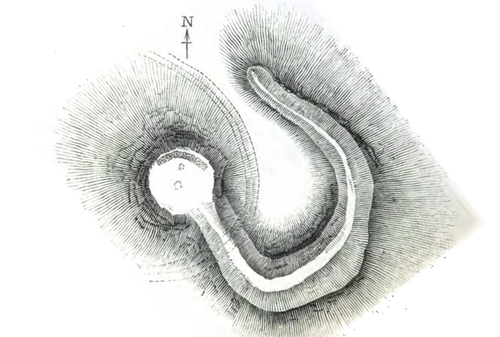

Skelmorlie serpent mound. 1871. Source: On Prehistoric Traditions and Customs in Connection with Sun and Serpent Worship, p31

From History of Skelmorlie:

...near to Skelmorlie castle at the Meigle is a 100 foot high artificial mound, said to have been the site of Sun and serpent worship. A Dr Phené discovered this structure and excavations revealed a paved platform shaped like a segment of a circle, together with many bones and charcoal.

History of Skelmorlie apparently quoted the above from p95 of Picturesque Ayrshire by William Harvey. Part of The Shire Series published by Valentine & Sons, Dundee, it is not (apparently) available online.

From Skelmorlie - Wikipedia:

To the south of Skelmorlie is the serpent mound, a prehistoric, perhaps druidic, site apparently carved either deliberately for religious uses or by nature then reused due to its natural shape.

It's easy to assume Skelmorlie serpent mound is Castle Hill - another mound a mile south east of Skelmorlie on the Old Largs Road (between South Whittlieburn Farm and Castlehill Cottages):

Castle Hill. Source: Skelmorlie - Wikipedia Commons

Location: Google Maps

However, although I very much doubt that Castle Hill is entirely natural, it seems to be a different mound. It is situated between different streams, by a different road and shows no sign of Skelmorlie serpent mound's tail or the excavations described at Skelmorlie serpent mound.

Skelmorlie serpent mound hunters may be mis-led by another Skelmorlie mound.

From Skelmorlie Reservoir Disaster:

Mr and Mrs Leitch of Croftmore Cottage and their son found safety in the mound of earth to the rear of their property.

However, that mound is probably Skelmorlie's (alleged) moot mound, not Skelmorlie serpent mound.

Skelmorlie moot mound: Google Maps.

Most of what we know of the location of Skelmorlie's mysterious serpent mound comes from Guide to Wemyss Bay, Skelmorlie, Inverkip and Larges, Reverend J Boyd, Alexander Gardner, Paisley, 1879, which quoted what Boyd described as 'additional notes about Skelmorlie Castle' taken from recent newspaper articles 1.

In fact, Boyd also quoted verbatim from Phene's description of his 'discovery' and investigation of Skelmorlie serpent mound as published in On Prehistoric Traditions and Customs in Connection with Sun and Serpent Worship, Dr John Samuel Phené, section 42, p30.

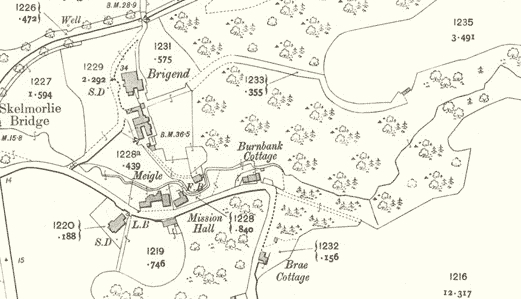

But helpfully, Boyd added more location information to Phene's text so I've reproduced it below. To make things easier, I've added back Phene's original illustrations. The Bridgend House Boyd mentions is at the southern end of Skelmorlie between Mill burn and Meigle Burn:

Bridgend House location. Source: Skelmorlie Villas

From Guide to Wemyss Bay, Skelmorlie, Inverkip and Larges, Reverend J Boyd, 1879, p14:

BRIDGEND HOUSE

A few yards south of Skelmorlie Castle, nearer the main road, is Bridgend House, a comfortable, cosy-looking residence, charmingly situated on a gentle slope, and securely sheltered from every wind. The house and grounds, extending to about forty acres, originally belonged to the Earl of Glasgow, but in 1814 they were purchased by Mr. Wallace of Kelly...

Behind Bridgend House is a hill or mound rising to a height of 100 feet, which has recently become an object of interest to the antiquarian.

SERPENT MOUND

It presents the appearance of an irregular hill or mound, partly overgrown with trees. That it is artificial there cannot be any doubt. In the newly published Geography of Ayrshire, issued by Collins, (Collins' County Geographies), there is the following reference to it - "In Skelmorlie is one of the most remarkable antiquities in Scotland: a 'Serpent Mound,' supposed to have been used by the ancient Britons in the worship of the sun and serpent, and in other religious rites."

The first to discover the mound, and to speak of it as connected with the worship of the serpent, was Dr. Phene of Chelsea, who has come to this district for several years during the summer months. He made several cuttings in the mount, and discovered the remains of bones and charcoal, and two or three years ago published an account of his researches in the Scotsman and Glasgow Herald.

If this be indeed a serpent mound, then it is closely connected with Druid worship; for the worship of the serpent by the Druids is a matter of history. Whatever may have been the true origin of this snake reverance, certain it is, that in countless old Gaelic legends of the West Coast and the Hebridies, the serpent holds a place of much importance. We are told how they were wont to place live serpents as symbols at the foot of the altar during the time of sacrifice. They were also in the habit of forming artificial mounds in the form of a huge serpent, and several of these have been discovered in Scotland through the investigations of Dr. Phene and others, the most perfect of which is the famous serpent-shaped mound of Loch Nell, near Oban. We give the account of the Skelmorlie mound in Dr. Phene's own words - "In my investigations in Scotland I have lately discovered, in Ayrshire, a monument which appears to combine the most important customs I have touched on in one.

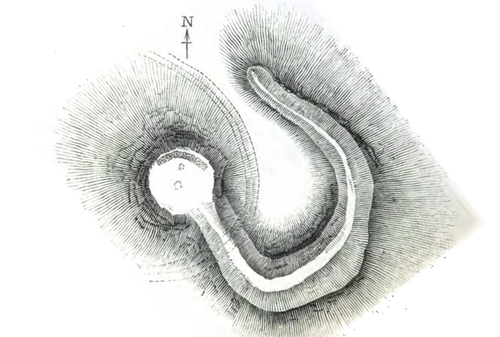

The Diagram represents the form of the mount with a large circular head and serpentine ridge 400 feet long.

Fig. 33. Plan of Mound (rotated to north). Source: On Prehistoric Traditions and Customs in Connection with Sun and Serpent Worship, p31

The broken curved lines indicate the Meigle road.

Continuing from Guide to Wemyss Bay, Skelmorlie, Inverkip and Larges:

It appears, though in a different attitude to the serpent mound in Argyllshire to bear the characteristics of a serpent emblem. Attracted by the outline, I excavated the mound, and discovered a paved platform of great interest. The hill is 100-feet high on its western side, is most uniformly shaped, and on the north and south sides measures 60 feet high ; to the east it is only 40 feet, and here its true circular form is lost, and a distinct elongation, terminating in broken ground, occurs just over a roadway formed at no very remote date. On the other side of this roadway similar broken ground, occurs where a beautifully curved serpentine embankment, 300 feet long commences. It is evident that the embankment once joined the circular mound or head, and was severed when the road was made. The embankment forms a ridge about five across on the top and was once nearly 400-feet long; it tapers as it recedes from the head and also slopes downwards towards the end or tail, terminating almost vertically, the earth having been retained in position by a facing of uncemented stonework, the remains of which still preserve the shape.

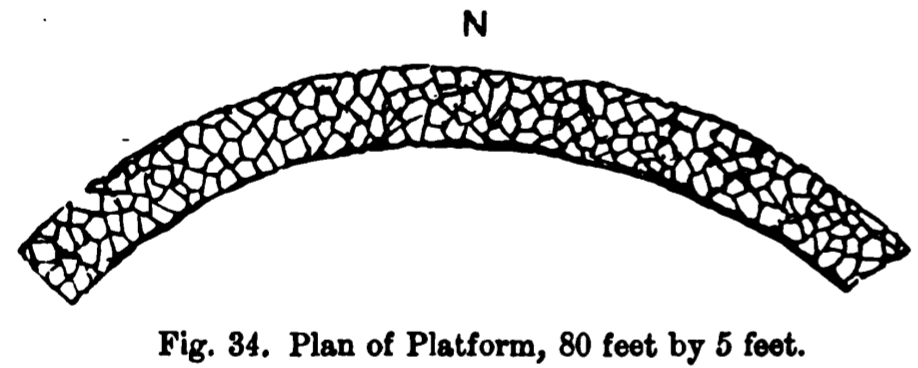

The ridge, which runs sinuously from the east side of the mound northwards, has been formed on the crest of a lofty bank, and is at an elevation of 130 feet above a stream still further north. The serpentine ridge did not contain any relics, but on cutting through it, its artificial formation was plainly shown, the materials having been brought from the adjacent sea-shore, and being quite distinct from the original summit, which was clearly denned. Trenches were cut in the head or circular hill at the four cardinal points, from the summit to the base, without any result; but on continuing these over the plateau, so as to form a cross, a divergence had to be made to avoid some trees, when the soil, hitherto of light colour, suddenly changed to black. This discoloration being followed, a paved platform was found about two feet, in some places, under a rich vegetable soil, which covered the whole hill uniformly, (except where it had been severed from the embankment), and which it must have taken ages to deposit, the trees that have been for many years on the hillock assisting little, as they are conifers. This discovery took place at the north-east, and was on the verge, just where the plateau joined the declivity. Cuttings were then made at intervals of a few feet all round the edge, in the same position, without success, till, on arriving at the north-west, the same appearance was exhibited. In result it was found that the platform was 80 feet long and 5 feet wide, paved with smooth flattened stones from the shore in a true curve, forming a segment of a circle, and covering a space between and including the north-east and north-west points of the compass.

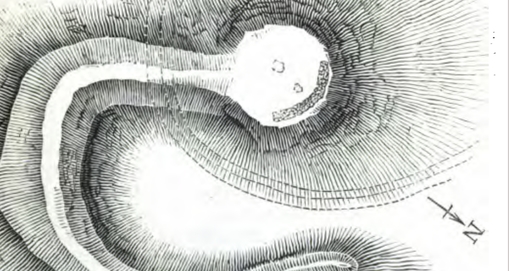

Phené's plan of Skelmorlie serpent mound's charred platform (his fig. 34). Source: On Prehistoric Traditions and Customs in Connection with Sun and Serpent Worship, p32:

The platform itself, and the earth beneath it to a considerable depth, were highly charred, large masses of charcoal filled the interstices between the stones, and on washing the earth obtained from the same position, it was found to be full of portions of bone, so reduced in size as to show that the cremation must have been almost complete. Taking the latitude of the mound, and the points of the compass where the sun would rise and set on the longest day, this segment-shaped platform, devoted apparently to sacrifice by fire, is found to fill up the remaining interval, and thereby complete the fiery circle of the sun's course, which would be deficient by that space. Near the centre of this hillock was found under the surface a larger stone than any on the hill, and which may have formed part of the foundation of an altar. Independently of the time of year indicated by this fire agreeing with that of the midsummer fires of the Druids, we have here not only an evidence of solar and serpent worship, but also of sacrifice."

Apart from historical interest, the mound and the adjoining glen are well worth visiting, if only for a sight of the flowers with which at certain seasons they are covered.

MEIGLE

Continuing the turnpike road and crossing the Skelmorlie and Meigle Burns flowing on each side of Bridgend, a road turns to the left, past a group of houses called Meigle, and where a small chapel has recently been erected - in November 1876 - by the Misses Stewart of Ashcraig

More confirmation that Skelmorlie serpent mound was - and perhaps still is - closer to Wemyss Bay's shore than Castle Hill mound and that it was situated between the Mill and Meigle burns (streams) comes from a description of Meigle - the hamlet immediately south of Skelmorlie.

From Meigle, North Ayrshire - Wikipedia:

Above the hamlet lies the 'Serpent Mound', named after the curved shape of the earthwork.

Smith records that despite the serpentine shape it is a natural stratified structure formed from stratified deposits on the old raised beach eroded by streams that run on either side.

'Smith' is John Smith of Dalry (short biography part 1), (part 2), whose Skelmorlie notes may perhaps be found in Books and notebook by John Smith - apparently held by the Robert Dick Institute, Elmbank Avenue, Kilmarnock, KA1 3BN. Telephone: Museums/Galleries: 01563 554343. Library: 01563 554300.

The map visible in that link does not include Meigle or Skelmorlie serpent mound (you can see a simplified copy of that map online) but perhaps the mound and tail are shown in some other part of John Smith's notebooks.

It's curious that in 1879 Reverend J Boyd said Skelmorlie serpent mound had 'recently become an object of interest to the antiquarian'. As if the mound were not curious before 1879. Or as if antiquarians didn't exist before 1879.

Other references to Skelmorlie's serpent mound suggest that from two years after Phene's discovery, the mound was being 'noticed' - ie written about - in tourist guides.

From Skelmorlie Ayrshire - Vision of Britain:

Under Largs are noticed the Skelmorlie Aisle and the 'serpent mound.' -Ord. Sur., sh. 29 (OS map sheet 29), 1873. See Eglintonn Castle; Gardner's Wemyss Bay and Skelmorlie (Paisley, 1879); and A. H. Millar's Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire (Edinb. 1885)

'Under Largs' means 'categorised near Largs'. Because both Meigle and Skelmorlie are immediately north of Largs. AH Millar's Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire doesn't mention Skelmorlie serpent mound at all.; This is rather odd considering its proximity to Skelmorlie Castle and its easy confusion with Castle Hill a mile to the south east.

Since its years of fame in the 1870s, there seems to have been an attempt to dismiss the mound as a natural feature or to 'forget' its peculiar structure and the problematic artefacts found in it.

For more examples, consider the following:

From History of Skelmorlie:

The mound itself may well be entirely natural, however the paved platform is a genuine artefact; it is not listed by the relevant authorities.

The above is a apparently taken from p6 of Skelmorlie: The Story of The Parish Consisting of Skelmorlie and Wemyss Bay, published by The Skelmorlie and Wemyss Bay Community Centre, 1968.

And consider the following:

From Skelmorlie: The Story of The Parish Consisting of Skelmorlie and Wemyss Bay:

In Skelmorlie is one of the most remarkable antiquities in Scotland a ‘Serpent Mound’, supposed to have been used by the ancient Britons in the worship of the Sun and the Serpent, and other religious rites. The head of the Serpent lies behind Brigend House and the ridge forming the body is now severed by the road running up the hill at Meigle. In the 1870’s Dr. Phené of Chelsea made some interesting excavations, discovering a paved platform some 80 feet long, and evidence of early cremations. The details were fully reported in the Glasgow Herald and the Scotsman at the time and there are specimens in the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow.

Recent examination of the pieces at Kelvingrove confirms that they are indeed burned human bones, something which was always disputed about Phené's original findings. Artefacts found at the Kempock Stone 2 during similar excavations in the 19th Century are now also due to be tested alongside items found during the controversial excavations at Langbank, recently rediscovered at the National Museum Edinburgh. It is suggested that dating of the artefacts and remains will show them to be contemporary, and that the strange serpentlike drawings uncovered on stones at Langbank are linked to the "serpent mound" at Skelmorlie, via some sort of celtic river or serpent worship cult.

I haven't been able to find 'Langbank' and its serpent art but the description sounds like Pictish rock art:

Abelermno Stone. Source: Rock Art of Scotland

Blue: Verified locations. Red: Serpent mound candidates

Map based on the following references:

- near to Skelmorlie castle at the Meigle

- Between two burns (streams)

- Near the beach

- The head of the Serpent lies behind Brigend House

- The hill is 100 feet high on its western side, the north and south sides measures 60 feet high

- to the east it is only 40 feet, and here its true circular form is lost, and a distinct elongation

- The ridge, which runs sinuously from the east side of the mound northwards, has been formed on the crest of a lofty bank, and is at an elevation of 130 feet above a stream still further north.

- The embankment forms a ridge about five feet across on the top, and was once nearly 400 feet long ; it tapers as it recedes from the head

- the ridge forming the body is now severed by the road running up the hill at Meigle

- "a significant population" lived around the area behind the present-day Manor Park Hotel

That more or less sums up what was reported about where Skelmorlie serpent mound was. Let's look at what evidence supports its use as a 'sacrifice' site.

Phene claimed that Skelmorlie serpent mound had been a sacrifice site of 'a magnficent scale':

From On Prehistoric Traditions and Customs in Connection with Sun and Serpent Worship, Dr John Samuel Phené, section 42, p30:

In Scotland also fire in connection with the cross was the signal for blood-shedding. 4

And from section 43:

Observe then, — with the Hebrews was the custom of keeping fire burning nocturnally, from sunset to sunrise, and this in connection with sacrifice; in the monument before us appears the same custom on a magnificent scale, viz., for a particular occasion the burning seems to have been so arranged as even to fill up the arc of the sun's disappearance from the point of his setting to his rising again, completing, as it were, the circle of his light and heat.

There, Phené is referring to how the paved area on top of Skelmorlie mound could be seen as an arc representing the northern horizon beneath which the Scottish sun dips at night. He is saying that by maintaining a moving fire on the paved arc, the mound's users could simulate the missing, night-time sun.

Maybe. Maybe not.

In addition to claims burned human bones were found in the mound, there is evidence the area around Skelmorlie serpent mound was involved with bone milling. Until about 1750, maps typically labelled the area between Mill burn and Meigle burn only as 'Mill'. See Skelmorlie - NLS side-by-side view: Roy 1752-55 Lowlands map.

As for why human bone might be milled, take an example from England.

From The Origins and Development of the British Coprolite Industry, Bernard O'Connor, 2001, p46:

The corn mills used by the agricultural suppliers were not able to meet the demand for bone meal and this led to the setting up of bone manure works. Their most popular products were half-inch bones. These were burnt or crushed and added to the soil as bone meal. ... However, the bones from the knacker's yards were insufficient to meet the demand of the nation's manure manufacturers, a factor that led to the import of dried bones. There were reports of cargoes of mummified cats from Eqyptian pyramids and sun-bleached bones from the North African desert and the Argentinian pampas. The battlefields of Leipzig, Waterloo and the Crimea were scoured for their bones and even catacombs in Sicily were empted. "Great Brtiain is like a ghoul, searching the continents for bones to feed its agriculture ... robbing all other countries of the condition of her fertility" (quoted in Keatley 1976).

So perhaps Skelmorlie's serpent mound supported a wind-driven bone mill.

See also Location Analysis: Clothall and Therfield Heath, Hertfordshire for evidence around - and at - The Mount at Sandon in Hertfordshire. The conjecture is these structures were burned down as part of a movement away from milling human carcasses to burying them. This would go a long way towards explaining why commoners' graves are rarely found from before 1792.

If local residents were being sacrificed on the mound by Meigle's farm managers (vicars/wiccas), where were the residents being farmed?

From Skelmorlie - Wikipedia:

It is known that "a significant population" lived around the area behind the present-day Manor Park Hotel in the 9th to 11th century, and evidence supports the theory that an early Celtic church existed there before the arrival of the Cluniac Monks (who formed Paisley Abbey in 1163) and the foundation of the Roman Church.

Also, there were three hill forts to the south of Skelmorlie and what appears to be evidence of carcass processing:

From Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire, John Smith, Elliot Stock, London, 1895:

This locality is quite famous for the number of archaeological remains that have been got at it. In making a road, a number of stone coffins were encountered, and at certain spots one has only got to dig perseveringly enough to unearth a cinerary urn ; and the number of these which have been got, and as a rule broken, is astonishing, and quite entitle the place to the name of Urnfield.

It seems we're encouraged to think a death cult operated around Wemyss Bay. Perhaps centred on Skelmorlie serpent mound.

However, this may be a cover story. explaining away burned carcasses left by a mass die-off. When you

When you look more closely at John S Phene and even Skelmorlie itself, strange connections emerge with another mass die-off.

More:

-

Skelmorlie. The Story of the Parish Consisting of Skelmorlie and Wemyss Bay, Walter Smart, 1968. Published by The Skelmorlie and Wemyss Bay Community Centre.

-

Picturesque Ayrshire. Dundee, William Harvey. Valentine & Sons.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

Fig. 33. Plan of Mound (rotated to north). Source: On Prehistoric Traditions and Customs in Connection with Sun and Serpent Worship, p31

Phené was very careful to get details of the platform area:

Fig 33. Skelmorlie summit: position of platform (enlarged). Source: On Prehistoric Traditions and Customs in Connection with Sun and Serpent Worship, p31

-

Folklore around the stone suggests it was a market stone for trading 'meat'. A 20mm (3/4in) hole bored into its base suggests it was used as a tether. Kempock stone folklore associates it with 'unlucky' marriages. ↩

-

The ridge and head are now severed by a modem roadway. ↩

-

For further particulars of these mounds see the author's papers in Reports of the British Association for 1870-71-72-73, and Proceedings of the Royal Institute of British Architects, 19th May, 1873. ↩

-

The symbol which summoned to arms. — Scott. Since reading this paper I have, through a suggestion by Mr. Wm. Simpson, discovered west of Bute a vast lithic temple (hitherto unrecorded) arranged in a serpentine form, with a cross transept, and having along its course evidences of internment; and on the Mendip Hills beautifully serpentine arrangements of barrows, evidently connected with the great religious places of the Celts. ↩

-

Phené's biography implies that he and/or his otherwise undocumented father William, were part of the 19th century Fenland Diaspora. ↩

-

This site conjectures the Huegenots were one of several north-west European groups who repopulated eastern England after a 17th century depopulation event. See On The Level About Lincolnshire - Part Three. ↩

More of this investigation:

Serpent Mounds

More by tag:

#mounds, #Tennyson friend, #tea merchants