Royston's name-explainers ignore its most elite resident. Sun 16 July 2023

Royston's (almost) unique town centre bottle cave. Source: Royston Cave

Since it was 'rediscovered' in August 1742, Royston Cave's under-town location, bottle shape and wall carvings have baffled historians:

The find beneath the grind. Source: Royston Cave - A Mystery beneath the Streets

If you're not already familiar with the Royston Cave mystery, do watch the 20-minute video at Royston Cave - A Mystery beneath the Streets.

But the cave is less of a mystery than it seems.

A 1649 Parliamentary Commissioners' plan of Royston's town centre the cave's location was known by the time the English 'Civil War' ended 1.

The cave is the circle drawn within Royston Cave's Buttermarket. Item 29 below:

1649 plan of Royston town centre. Source: A History of Royston, Alfred Kingston, 1906

The Buttermarket building of 1649 even looks like a housing purpose-built to enclose Royston Cave.

The 1649 plan agrees with modern plans:

2016 plan of cave's location. Source: Royston Cave

If the Victoria County History of Royston Parish is correct, Royston market had been owned and managed by Royston Priory since 1189. Directly above the cave.

It also held the right to execute on a gallows and the right of murder.

Victoria County History tells us Royston Priory's first prior 'Simon' fell out with the Abbot of Westminster and - presumably - the master of the Knights Templar over the priory's market fees. It tells us this dispute continued through several priors from 1109 until 1308.

The names of the various Abbots of Westminster and - presumably - masters of the Knights Templar between 1109 and 1308 are listed here.

In 1308, it says, men from (allegedly) Knights Templar-owned lands to the north west of Royston (Bassingbourn, Cambridgeshire) and south of Royston (Newsells and Kelshall in Hertfordshire) assaulted Royston's prior.

Coincidentally, the Knights Templar were disbanded in 1308. Or so we're told.

So the orthodox Royston Cave narrative puts the town at the centre of warring religious factions. However, when we look at land owners in and around Royston we find some surprising names.

Royston's hidden owners:

Starting with the Royston faction, we are given names for some of the market's owners. Which means we're given the names of individuals who should - theoretically - have known Royston Cave existed.

Before the cave's re-discovery, the market's last known manager was Richard Bretten. Bretten was the 'prior' of Royston Priory from 1534 until 1537. He surrendered the priory's holdings in March 1537 - at the Dissolution of the monasteries.

Keep in mind that the IHASFEMR model interprets abbeys, monasteries, friaries and priories as historical camouflage for abbatoirs, meat processing and hospitality venues. IHASFEMR would expect Richard Bretten to dress like a butcher, occasionally wear chainmail. And wield knives, machetes and hunks of meat.

Royston Cave's tourist narrative leaps over the next two centuries. It picks up with the cave's next known promoters - and perhaps its owner/managers. They were George Lettis, bailiff of Royston manor, and William Lilley, a 'tailor' who lived in the house next to the cave at the time of its 1742 're-discovery'.

You would think both men would have known who had owned Royston manor, its market and - critically - the structures and legal rights attached to the market immediately before the cave was re-discovered.

From Parishes: Royston - Victoria County History:

In May 1537, shortly after the dissolution of the priory, the market, fairs, court of pie-powder with the stallage and piccage and the profits of the windmill of the late priory were leased to Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell transferred his interest in the market to Edward Annesby.

Nevertheless in 1540 a grant was made to Robert Chester of all the possessions of the priory 'with two fairs, one lasting throughout Whitsun week, the other on 7 July and the two days following, and a market on every Wednesday at Royston.' The claims of Annesby and Chester were considered by the Court of Augmentations between 1540 and 1544, and apparently the decision was in favour of the lord of the manor (meaning Robert Chester). The profits of the fair and market have since remained with the successive lords.

Whoever owned or administered the right of 'piccage' - the right to dig the ground beneath the market - would have known where the cave was.

Lord Robert Chester passed Royston manor, its market and its 'piccage' on to his son Edward Chester. The Chester's ownership trail is described in Parishes: Royston. It ends with another Robert Chester passing Royston manor - and the rights to its market profits - to another Edward Chester. It's not clear which of them owned the manor and market at the time the cave was discovered. But it is highly unlikely the Chester family forgot the strange cave beneath their manor. And its market revenues.

It's possible the Chester genealogy was faked. For example, we're told Robert Chester bought the manor in 1537 but was granted it in 1540. A possible date mismatch.

Another mismatch appears in Royston's ownership trail.

We're told Robert Chester passed it on to his son Edward Chester. However, we're also told a 'Chester' bought the manor and eventually passed it on to a son named Robert Chester, not a son named Edward Chester.

From James I's Royal Palace, Royston:

James [VI of Scotland (James I of England)] arrived at Hertfordshire’s border on 30 April 1603...

and was entertained by its owner, Robert Chester, whose father had purchased the Priory estate following its dissolution in 1537.

These repetitions of names and discrepancies in who passed the manor on to whom hint at forgery in the Chester family tree. And in Royston manor's chain of ownership.

That's a reasonable claim because elite claims to land ownership are often based on forgery. Especially as the Reformation stripped land from its previous owners.

From William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley:

It was the conscious and unconscious aim of the age to reconstruct a new landed aristocracy on the ruins of the old, Catholic order.

This is why unknown 'old' English families suddenly emerge from 'old' documents. Old documents whose source is also unknown.

From Proofs of Age of Sussex Families, edited by William Durrant Cooper, in Archaeological Collections, Relating to the History and Antiquities of the County of Sussex, 1860, p23:

The transcripts, which I now edit for our Society, have been most kindly placed at my disposal by a friend

Not only do these records recover for us several families, whose names even have passed from our ordinary knowledge, but they furnish us with authentic particulars relating to such families as DeBohun and Dalingregge, hitherto undiscovered;

If ownership of Royston manor was forged, what does the forgery hide?

From James I's Royal Palace, Royston:

Chester, who had since been knighted, agreed to rent his Priory House to the King for one year.

the King announced a 14 mile wide hunting ban surrounding Royston, so that hares, rabbits, partridges, marsh hens and other game would be preserved for his pleasure. A gamekeeper was appointed to protect the game from poachers; huntsmen were hired to care for the King's hunting dogs; and a vermin keeper was assigned to kill foxes, badgers, predatory birds and any other ‘vermin’ which preyed on the King's game.

That's a kill-zone the size of modern London:

Royston Cave was at the centre of a 615 square mile kill-zone.

Clearly, King James I's 1603 rule over Royston was tough on any locals who relied on pre-existing hunting traditions.

And as with Royston's earlier priors, James I's interpretation of free markets created more problems for the locals.

From James I's Royal Palace, Royston:

Horses and transport were also often taken from locals, usually under extortion, bribery or threats from royal workers, and resources were drained to accommodate royal visits.

James I's activities in Royston also triggered two major historical events:

-

We're told his poor treatment of the locals helped provoke the 1605 Gunpowder Plot. The Gunpowder Plot is itself another alleged spat between elite warring religious factions. It was investigated and resolved by William Cecil of Burghley House. Though perhaps more as author than detective.

-

Royston is where James I made a 1612 deal to marry off his daughter Elizabeth Stuart to Frederick V, Prince Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire.

From The Lasting Legacy of Elizabeth Stuart, the ‘Winter Queen’:

By all accounts, she had an idyllic childhood.

The Harringtons indulged her love of nature: They constructed several buildings on their estate containing paintings and stuffed animals in addition to an aviary and menagerie, complete with a selection of miniature cattle from around the British Isles. Elizabeth referred to this as her “fairy farm.”

From Who Was the 'Winter Queen'?:

the German-speaking groom uttered his well rehearsed vows in English

The teenage bride’s inability to stifle her giggles through her wedding vows... may have been occasioned by the mischievous groom’s wedding gift of a monkey house

Good gift for a woman whose father owns a huge hunting park:

A zoo and a monkey house. Source: Westworld

The reference to a monkey house may also explain rumours the Bohemian royals threw pieces of meat at their servants.

The significance of that marriage in England is that it allegedly entitled the current royals to the English throne.

The remarkable claim promoted as the great Royston Cave mystery is that the cave remained - or became - forgotten even while James I filled the town with local and international hunters and diplomats. That the cave was forgotten even as the Buttermarket above it grew busier providing supplies for the town's elite visitors.

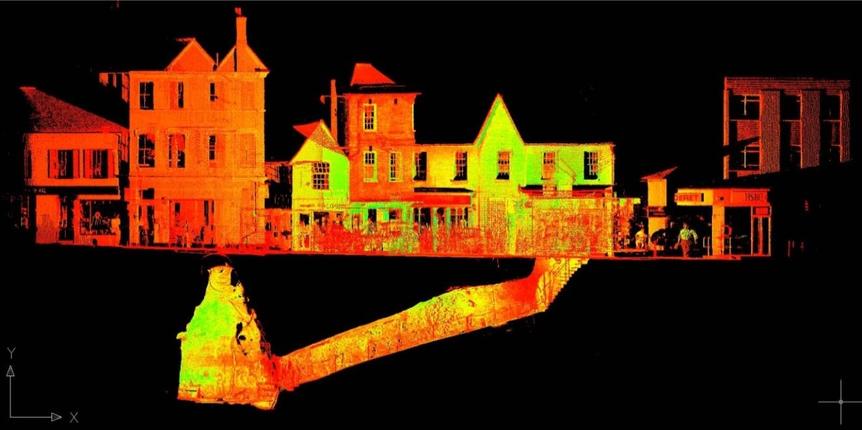

The Buttermarket is to the right of this artist's impression of the southern end of the palace as surveyed in 1649 Royston:

James I's wardrobe at top centre; Buttermarket to right. Source: James I's Royal Palace, Royston

The two identical long wardrobe buildings are item 6 in the 1649 plan at the top of this page. The plan labels the circular building on the left as the King's 'cock-pit'.

How Royston got its name:

James I's and his activities rebuilt and expanded Royston. Early 19th maps show Royston's built area was still approximately as it was in 1649. As King James I left it.

It's odd then that British historians don't link its name to its grand resident.

In Palaeographia Britannica: or, Discourses on Antiquities in Britain. Number I, 1743, William Stukeley quotes William Camden's explanation of how Royston came to be called Royston. According to Stukeley, Camden said the name 'Royston' dates from when the monastery - Royston Priory - arrived:

Upon this occasion inns began to be built, and by degrees it came to be a town; which instead of Royses Cross, took the name of Royses town, contracted into Royston.

Stukeley did not point out that Camden wrote this shortly after 1607 - when Roi James I was four years into expanding Royston as a back-up London. Instead, Stukeley and subsequent writers promoted the notion that Royston was name for the 'supposed' countess Lady Roysia.

Even though Royston was the King's town, the Roi's town.

Royston mystery narrative also hints that wordplay was used to smudge out James I's association with the owners of Royston market and cave beneath.

From James I's Royal Palace, Royston:

James was last at Royston in February 1625, where he created his final knight, Sir Richard Bettenson.

'Richard Bettenson' is curiously similar to that other 'final' Roystonite: the prior 'Richard Bretten'. Sometimes spelled 'Richard Bretton', Bretten was the 'final' prior of Royston at Dissolution in 1537.

This resemblance of a 17th century Royston knight to a 16th century Royston 'prior' echoes the technique identified in Who Faked the Cromwells?, where history's problem areas are back-filled by creating two characters out of one.

In its A History of Royston, Royston Museum also hints at another possible end-of-use date for Royston Cave. It suggests the royal buildings at the centre of Royston were used until 1647, when Charles I last dropped by:

as a prisoner of the Parliamentary army during the Civil War. Afterwards, the buildings fell into disrepair.

That suggests demand for the market's produce lasted until shortly before November 1647.

Similar blurring of narratives has derailed understanding of Royston Cave's structure and its carvings. This blurring is explored in the next part.

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

1649 marked the first year of the English Commonwealth after the English Civil War. It lasted 11 years. ↩

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis: Royston Cave,

More of this investigation:

Location Analysis

More by tag:

#sheela na gig, #Manimal Farm, #hunting humans