Logic and folklore explain enigmatic landscape features and suggest an origin for 'the Stations of the Cross'. Wed 15 June 2022

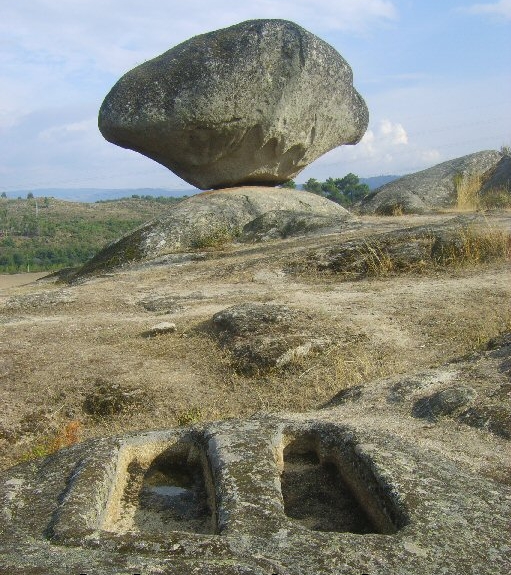

Pedra do Sino (Bell Stone) and 'rock tombs' at Necropole de São Gens, Celorico da Beira, Portugal. Source

Rock tombs are found in Portugal, Spain, Italy and France. They can be found in one place in England, and have been reported in Ireland and the Isle of Man.

Portugal's rock tombs often come in pairs as part of larger clusters:

Two of 60 rock tombs at Fornos de Algodres, north Portugal.

Officially, Portugal's rock tombs are dated to medieval times. So are France and England's. Italy's rock tombs are credited to both medieval times and to the mysterious pre-Roman Etrurians. The Romans allegedly conquered the Etrurians from around 500 BC onwards. Making their rock tombs up to 2,500 years old:

La Necropoli dei Morticelli, Vasanello, Italy. Source

Clusters of rock tombs that were populated must have been impressive places for reflection:

But not necessarily for grieving. Source: Abandoned Rock-cut tomb necropolis

This is part of a bigger cluster in the centre of Trancoso village, Serra da Estrella, Portugal.

Trancoso's cluster begins to unravel the official story of rock tombs because it risked contaminating local water, local air and the fingers of curious children.

Yet the biggest rock tomb complex on the Iberian peninsular lies in a village:

Amid other clues to their real function. Source: Finally, Moreira de Rei gave up her secret

See the stone cross on the right? With the troughs and jars next to it. Tap on the image to pull up a larger version.

Italy's rock cut tombs also help unravel the official explanation.

Many Italian rock tomb clusters - Etrurian and otherwise - can be explored along Rome's busy former slave-trading route: the Via Amerina:

Via Amerina about 50km north of Rome. Source: Via Amerina

Via Amerina conveyed slaves - and today tourists - past many mysteries:

Yes. The livestock end of the agriculture...

England's only known rock tombs were (apparently) first documented 200 years ago in 1830. But they got their real break in the 1970s:

Rock tombs at St Patrick's chapel, Heysham, Lancashire. Source

Heysham's rock tombs are unique.

From Britain Express: St Patrick's Chapel, Heysham:

Several of the graves have carved sockets at the head end that probably supported stone crosses.

They mean a second socket just beyond the head end of the tomb:

Five of six tombs have extra sockets. Source:

Five of Heysham's six main tombs feature a separate cross socket. Two smaller Heysham rock tombs - the so-called 'child and adult' tombs - share a socket between them.

If the 'sockets for crosses' explanation is correct, then perhaps Portugal's occasional circular 'head' notches supported cross shafts made from unworked tree trunks:

Head notch at Sepultra da Cova da Moira, Carregal do Sal, Portugal.

In all countries, the official explanation claims rock tombs offered this variety to rich medieval children and/or various members of the elite.

Note how some rock tombs have no head notches; some have square head notches, some have circular head notches. A few have wedge-shaped notches and a very few have keyhole-shaped notches.

Different shaped head notches (and other features in and around rock tombs) suggest different tombs were designed to serve different processing purposes.

Similarly, careful analysis of wear patterns and damage also hints that specific processes may have hurried decomposition along in some tombs.

There is a pressing need to catalogue wear and damage patterns in order to better understand the practice of assisted decomposition in their locations.

This isn't the place to justify the need for that level of analysis, so I'm going to try to evidence one specific use case.

Many Portuguese rock tombs show signs of deliberate destruction. A good example is the Sepultra da Albergaria rock tomb just south of Carregal do Sal:

The sign says Albergaria rock tomb was destroyed.

It took hard work to smash out the rock sides of the Albergaria tomb. These photographs don't do justice to the damage. Nor to the work required:

And anyway, why so much effort to smash a child's tomb?

Of the Carregal do Sal cluster, the Albergaria tomb is the tomb closest to town and closest to the road leading to the River Mondego. It was the easiest tomb to get at and probably the tomb most often passed after its creators stopped using it.

Also enigmatic and unanswered is the question: why are rock tombs are so often found near quarries?

Quarry face below Heysham rock tombs. Source: Phil Platt/Google Maps

The shaped boulder at bottom right in the former quarry at St Patrick's chapel is reminiscent of 'Pedro do Sino' - the curvaceous boulder that overlooks rock tombs of Portugal's Necropole de São Gens:

It is conceivable that rock tomb complexes were bathing stations for quarry workers. But given their positions high above quarry faces, this seems unlikely.

Fortunately, Portuguese folklore applies Maslow's Razor 1 to this enigma and begins to explain what one class of 'rock tomb' may have been used for.

From Enchanted Moura:

Rock cut tombs called Masseira... the place where the mouras knead bread.

'Masseira' means 'trough' or 'manger'.

'Mouras' are supernatural females somewhat like northern Europe's witches though with more of a 'local manageress' role. They may be the same entities as Celtic 'Morrigans'. They are everywhere in northern Portugal's folklore.

Southern Europe's artisans still use masseira:

Massaging the mass in a manger. Source: Tradition of Open-Air Pig Slaughter Abides on Spanish Island

They are preparing the filling for blood sausages.

Blood sausage is made throughout Europe:

French blood sausage packed in intestine. Source: Blood Sausage

Francisco Ubilla photographed this process in 2018. See more of his images at Tradition of Open-Air Pig Slaughter Abides on Spanish Island.

England's variant of blood sausage is "Black pudding". Black pudding is most popular in England's north and west; in places like Heysham, Lancashire.

From Black Pudding:

Black pudding is a distinct regional type of blood sausage originating in the United Kingdom and Ireland. It is made from pork or beef blood, with pork fat or beef suet, and a cereal, usually oatmeal, oat groats, or barley groats.

Each ingredient that goes into blood sausage has its own processing and hygiene requirements. Butchers use specialist tools and infrastructure to help manage these processes.

From The Facts of Crucifixion:

Flogging, or scourging, was done before every crucifixion.

Blood loss was considerable.

How long he lived depended mostly on how severe the scourging was.

Christian narratives of crucifixion don't say much about what happened to the blood. Fortunately, a few images do:

Blood collection bowl at well-known crucifixion. Source: The Templar Knight

Almost every rock tomb anywhere has been picked clean or repeatedly filled with rainwater. But at two rock tomb complexes in Portugal, archaeologists found these:

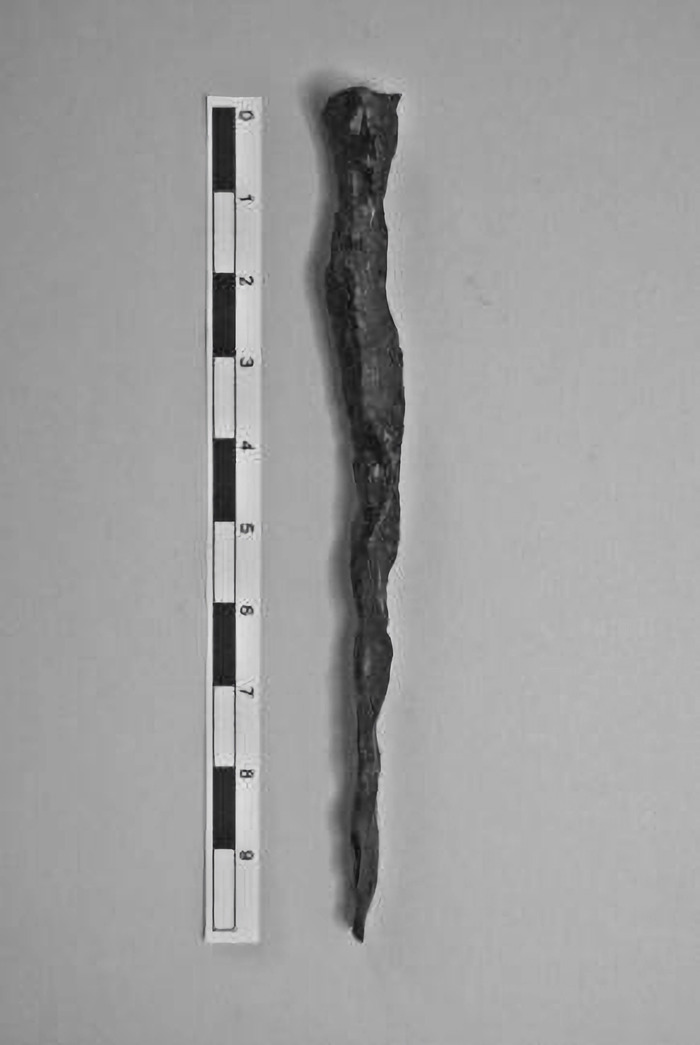

Spike found at Vale de Bexiga. Source: As Necrópoles alto-medievais da Serra de São Mamede, Sara Prata, 2012, p139

Some are spikes and some are nails. But shape and size suggest these aren't coffin nails:

Spike found at Vale de Bexiga. Source: As Necrópoles alto-medievais da Serra de São Mamede, p139

Spike found at Vale de Bexiga. Source: As Necrópoles alto-medievais da Serra de São Mamede, p140

Nail found at Vale de Bexiga. Source: As Necrópoles alto-medievais da Serra de São Mamede, p140

Spike found at Vale de Bexiga. Source: As Necrópoles alto-medievais da Serra de São Mamede, p140

Spike found at Vale de Bexiga. Source: As Necrópoles alto-medievais da Serra de São Mamede, p140

Why would you need spikes near rock tombs?

Christians say 'cross'. Butchers say 'gallows'. The device that also gives its name to 'hallows', 'hallowed', 'All Hallows Eve' and 'Halloween'.

From Roman Forms of Crucifixion:

Roman historian Seneca the Younger indicates:

"I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground"

Seneca seems to be describing primary butchery in an artisanal environment.

Victims still have their head down in modern industrial environments:

But modern industrial environments use metal 'tombs'. Source: AMI: Tour of a Pork Plant

Carcass processing volumes are very high in modern primary butchery processes. But the volume of product per carcass - and their individual handling requirements - likely remains more or less the same as in the days.

Butchering an adult human releases about five liters (1.5 gallons) of blood plus lengths of slippery, hard-to-handle intestine:

- Adult human's large intestine: approx 1.5m (5ft) long.

- Adult human's small intestine: approx 6-7m (20–25ft) long.

Intestine management means hygiene management. For profit and hygiene reasons, blood and offal must be collected and the intestines kept separate.

Is 'tomb' derived from 'tumbling'? Source: AMI: Tour of a Pork Plant

It's an offal pun.

Intestines destined for blood sausage must be squeezed clean. Then they must be cured in a trough of salt water or by drying.

While they dry, they must be kept clean and undamaged:

Modern artisans use trees. Source: Tradition of Open-Air Pig Slaughter Abides

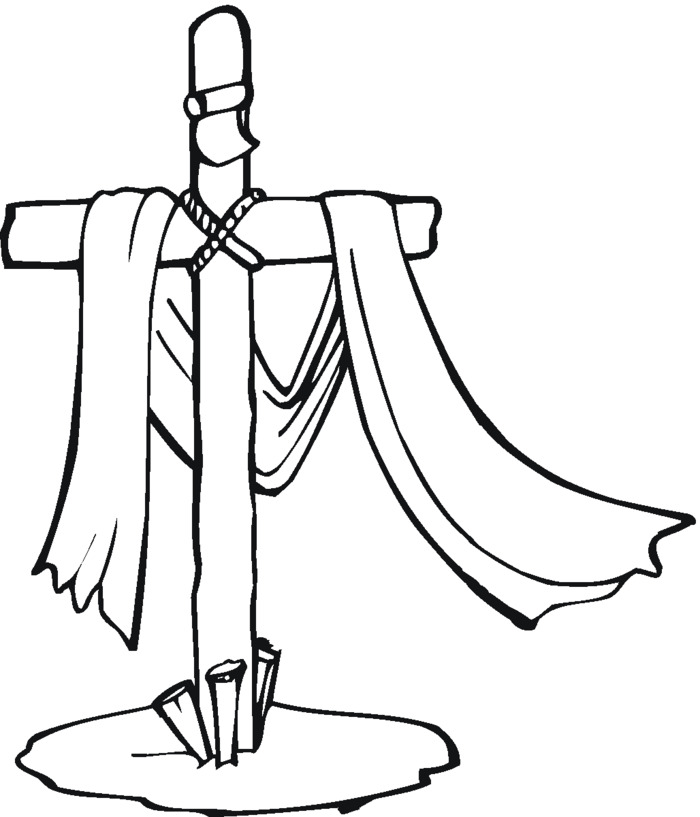

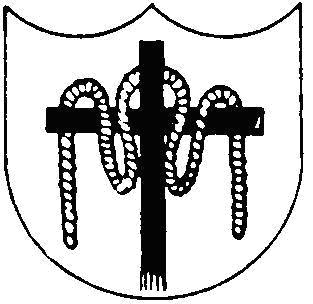

Symbols reminiscent of these processes can still be found from eastern Europe into Russia:

This imagery is called "Julia's Rope". In Romance languages, 'Julia' is pronounced with an initial 'H'. So that 'Hoolia' sounds similar to the initial sound of 'hallows'. Perhaps it's eastern European for 'Hallows Rope'.

In sanitised form, this symbolism has also made it into the stories Westerners tell their children:

"An interesting way to learn about one’s culture and religion." Source: Best Coloring Pages for Kids

Subsequent articles in this investigation present more evidence for why rock tombs' true purposes may have been 'forgotten'.

Locations discussed in this evidence collection

Key:

- Blue marker: rock tomb sites

- Yellow marker: Vale de Bexiga rock tombs

© All rights reserved. The original author/creator of each image, video, quote or text retains full ownership and rights.

-

Maslow's Razor: Animals prioritise physical needs before spiritual needs. Ancient relics reflect this. ↩

More of this investigation:

Away in a Manger,

More of this investigation:

Misunderstood Technology

More by tag:

#human meat, #human fat, #manimal farm, #geology